![]()

1. Africa: The Introduction of Christianity

The passage from traditional religions to Christianity was arguably the single most significant event in African American history. It created a community of faith and provided a body of values and a religious commitment that became in time the principal solvent of ethnic differences and the primary source of cultural identity. It provided Afro-Atlantic peoples with an ideology of resistance and the means to absorb the cultural norms that turned Africans into African Americans. The churches Afro-Christians founded formed the institutional bases for these developments and served as the main training ground for the men and women who were to lead the community out of slavery and into a new identity as free African American Christians. Religious evolution was not a single process but several processes operating at once.

Africa is the starting point for the historical trajectory of religious change. Unfortunately the historical study of precolonial African religious systems is severely hampered by a lack of data. Most of our knowledge of African religions in the past derives from biased European accounts or from inferences drawn from African religions in the present. Material evidence uncovered by archaeologists and systematic analyses of language evidence and oral traditions hold out some possibility for at least a partial reconstruction of early concepts and practices.1 In the meantime, our understanding of African religious beliefs and practices consists, for the most part, of representations of African religions as European missionaries saw them. Religiously arrogant, some missionaries denied that Africans had any religion at all; others recognized African religiosity but assumed the superiority of the Christian God to African divinities and struggled relentlessly to convince African peoples of that “truth.”2

The necessity of relying on missionary records has also contributed to an historical preoccupation with the first period of encounter and has created a false impression of what T. O. Ranger has called the “timeless” character of African religions. In fact, indigenous African religions had been undergoing changes for centuries, some of them precipitated by internal developments, some of them by external forces, such as war. The anthropological focus on the twentieth century also ignores change and development, and assumes the “quintessential identity” of Christianity and of indigenous religions.3 Social and cultural anthropologists have been recently challenged by a new wave of scholars, many of whom are affiliated to such disciplines as theology and comparative religion and have created their own theoretical orthodoxy. Labeled “Africa worshippers,” or the “Devout Opposition,” by Robin Horton, they depict Africans as uniquely religious and, strongly influenced by their own Christian faith, claim universality for the conception of God in all systems of African religious thought.4

Robin Horton has posed a conceptual challenge to the growing popularity and influence of both the anthropological and the “Devout” approach. In a seminal article published almost a quarter of a century ago, Horton sketched the broad outlines of a general theory of conversion. It rested on the premise that all human societies develop and adjust cosmologies in response to changing social conditions. In the case of West and West Central Africa, traditional religions that had developed within the microcosm of the local community were rendered unsatisfactory by the massive development of commerce and communication and of nation-states, which weakened the boundaries of local communities and raised doubts and anxieties about the ability of traditional cosmologies to explain or control events in a changing world. African peoples responded by making cosmological adjustments and ritual changes. These developments were well underway, Horton theorizes, when Islam and Christianity were first introduced into Africa. Thus African acceptance of Islam and Christianity was “due as much to development of the traditional cosmology in response to other features of the modern situation as it [was] to the activities of the missionaries.”5

In a more recent elaboration of this theory, Horton describes African Christianization as two mutually reinforcing processes wherein missionaries “extracted” basic religious ideas and terminology from the peoples they encountered and reinterpreted or translated them in terms of Christian discourse. Indigenous peoples, for their own reasons, responded by adopting in whole or in part that which they found useful in Christian theology.6 The outcome of the dialectic between missionaries and “converts” was forms of Christianity that, in T. O. Ranger’s formulation of the Horton thesis, were “shaped as much by the ‘converts’ from below as by the missionaries from above.”7 The dialectic was continuous, marking not only the first period of encounter in Africa but also extending to and including the process of interaction between Christian missionaries and Africans in New World societies.

Religious development in the New World was, as John Thornton has observed, an outgrowth of prior religious development in West and West Central Africa. Since much of it predated the Reformation, it was, for the most part, dominated by Catholic rather than Protestant efforts. The Portuguese were the first in the field, having made the initial contacts with Africans on the western coasts some fifty years before European voyagers departed for the New World.8 There are only a few scattered references in European accounts to the first African converts, but they appear to have been captives who had been sold into slavery in Portugal, where they were taught to read and write and to speak Portuguese. Once they “adopted” the religion and language of their masters, many of them were purchased and freed to serve as interpreters aboard Portuguese trading vessels.9 At least nominal adherents of Christianity, they served Portugal as the first cultural missionaries to West African peoples.

It took very little time for Catholic countries to realize that the best prospects for achieving their commercial and spiritual goals was contingent upon gaining the active support of the political leadership of the various African kingdoms. They became key religious targets. One of the earliest original accounts of European conversion efforts was left by Alvise da Ca’Mosto, or Cadamosto, a twenty-three-year-old Venetian sailor in Portuguese service. Cadamosto’s first voyage took him past Arguim, the first factory, or feitoria, founded by Portugal in 1445. By the time Cadamosto arrived ten years later on his second voyage, the trade at Arguim amounted to roughly ten thousand slaves a year, an indication of the rapid growth of the slave trade to the Americas.

From Arguim, Cadamosto sailed southward to the mouth of the Senegal River, a fertile, low-lying region inhabited by the garrulous Jalof, or Wolof, people and ruled by a chief called Budomel. Here in the Kingdom of Senega, as he did at Arguim, Cadamosto reported the strong presence of Islam. Introduced into the region by Arab merchants who had been carrying on a lucrative trade between the Barbary ports and the important interior port of Timbuktu since the eleventh century, the faith was jealously guarded from Christian competition by the local Muslim clerics called malams, or marabouts. Their opposition proved to be a major impediment to Portuguese dreams of gathering a rich spiritual harvest in Upper Guinea.

Cadamosto’s account of his debate with Budomel over the relative merits of Christianity and Islam is interesting for the light it throws on the process of conversion. With characteristic confidence in European cultural superiority, Cadamosto proclaimed to the chief “that his faith [was] false” and that the malams who instructed him in it were “ignorant of the truth.” However, his easy optimism over “getting the better” of the malams in debate was soon tempered by Budomel’s response: “The lord laughed at this, saying that our faith appeared to him to be good” because “God had bestowed so many good and rich gifts and so much skill and knowledge upon us [but that he had not given us good laws].” But “to the negroes, in comparison with us,” God had given “almost nothing” except good laws. Although his traditional religion had no well-defined idea of heaven or a hereafter, Budomel’s interpretation of Christian theology anticipates African American Christian notions of divine justice as well as a disconcerting sense of their own ethical superiority: “He considered it reasonable that they would be better able to gain salvation than we Christians, for God was a just lord, who had granted us in this world many benefits of various kinds. Since he had not given them paradise here, he would give it to them hereafter.”10

Budomel’s tendency to look on Christianity as a source of material rather than spiritual power was characteristic of the response of many African rulers during the early years of cultural encounters. It was in part generated by the fact that Europeans cultivated the friendship of the kings of Guinea by giving them gifts, in effect paying an annual tribute. For example, Diogo Gomes won the confidence of Battimansa, lord of the land around the estuary of the Gambia River, by giving him “many presents.” The apparent connection between the pearls of heaven and earth was not lost on the shrewd Battimansa, who invited Gomes to debate a local malam. Gomes’s proselytizing so impressed Battimansa that he ordered the malam expelled from his kingdom and proclaimed “that no one, on pain of death, should dare any more to utter the name of Muhammad.” Battimansa professed a sincere belief in “the one God only” and pleaded for baptism, but Gomes declined on the grounds that as a layman he lacked the authority. Gomes’s success in trafficking and communicating with African rulers convinced the infante to send the first mission to the Gambia in 1458.11

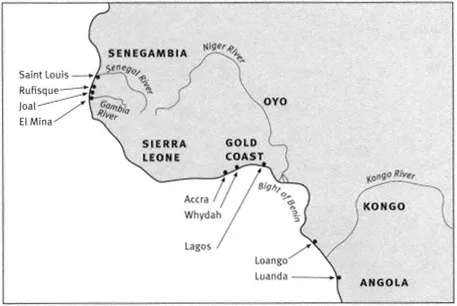

Map 1. West and West Central Africa in the Eighteenth Century

King João II entertained no doubts about the causal relationship between Portuguese tribute and the conversion of African kings. Indeed, it became a major factor in Portuguese diplomacy beginning in 1482, when the fortress of São Jorge Da Mina was built on the rocky headland of the Mina Coast. João gave classical expression to that policy when he ordered the construction of a church at São Jorge, “knowing that in the land through which ran the traffic of gold the negroes liked silk, woolen and linen clothes, and other domestic goods … and that in the trade with our men they showed they would be easily converted. … Thus, with the bait offered by the worldly goods which would always be obtainable there, they might receive those of the Faith through our doctrine.”12

Between 1482 and 1637, when the Dutch captured the last Portuguese fort at Axim, the governors of São Jorge and the other minor forts in the area were in continual negotiations with the rulers of the coastal kingdoms, who controlled access to the trade routes into the interior gold-producing regions of Denkyira. Sporadic attempts were made to convert the Comani people, who inhabited the kingdom of Commenda, to the west of Mina, and the Fetu, who lived to the east of it. The conversion of Sasaxy, king of the Fetu, in 1503 exemplifies the symbiotic efforts of African rulers and Europeans to gain advantage from that kind of relationship. At the insistence of the Portuguese governor, Sasaxy sent his son and a member of the royal court to the castle as hostages as a sign of good faith. In exchange he demanded that the Portuguese build him a house and chapel and provide him with a mule or a horse and two leather trunks in which to store his gold. Once the chapel was complete Sasaxy and 300 members of the royal household and roughly 1,000 of his subjects “received with much devotion the water of baptism.”13

In time, and very much on their own terms, other local rulers did accept Christian baptism, and small clusters of African Christianity slowly appeared on the western coasts near Portuguese settlements in Upper Guinea, Sierra Leone, and the Gold Coast. Eager to penetrate the interior and secure a larger and more constant supply of slaves, in 1481 the Portuguese established contacts with the highly organized city-state of Benin, which, until the eighteenth century, was a major center for European trade in the great delta of the Niger River. The idea that Benin was fertile ground to propagate the faith stemmed from early reports that the Oba, the temporal and spiritual ruler of the Edo people, was an adherent of some form of Christianity. But over the next 200 years intermittent efforts by Spanish and Italian Capuchins to convert the warrior obas and their people encountered considerable resistance. The imperviousness to Catholicism displayed by the Edo people and the rise of the delta villages of Bonny, New Calabar, Old Calabar, and Brass, led to the precipitous decline of Benin. At the same time, the counter-Reformation turned the attention of Catholic missionaries away from Africa and brought a temporary end to missionary activity in the Niger Delta.14

It was a different story south of the River Zaire in the old Kingdom of Kongo. John Thornton calls the conversion in 1491 of the mani Kongo, King Nzinga a Nkuwu, and his son Mvemba a Nzinga “the crowning achievement of nearly a half century of missionary efforts in western Africa.”15 Portuguese success in forging an alliance with the Kongolese monarchy was, in large measure, due to a compatibility of interests and needs, which until the seventeenth century involved the exchange of military assistance during the Kongolese wars of expansion for slaves acquired from peripheral areas of the kingdom. The “Christian Revolution” that accompanied the alliance involved the assimilation of those aspects of Christian cosmology that both harmonized with the Kongolese’s own view of the universe and served their needs and interests.16

In the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, the mani Kongo and the dominant Mwissikongo elite of the Kingdom of Kongo legitimated their political power by establishing a Christian cult under the direct control of the mani Kongo. When the first Portuguese arrived in 1483 the Kongo regarded them as water or earth spirits, in part because they came from the sea, which in Kongo cosmology was a barrier between the earthly and spirit worlds; the King of Portugal was called nzambi mpungu, or “highest spiritual authority.” The mani Kongo’s baptism was thus an initiation into the Christian cult. Not by coincidence, the mani Kongo chose as his Christian name João, the same name as the Portuguese king. Within a few years, João’s wife and son, Afonso, and a majori...