- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The North Carolina Roots of African American Literature by William L. Andrews in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Moses Roper, 1815

Moses Roper (from the 1848 edition of his Narrative) (Documenting the American South, <http://docsouth.unc.edu>, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries, North Carolina Collection)

“I have never read nor heard of any thing connected with slavery so cruel as what I have myself witnessed,” the author of The Narrative of the Adventures and Escape of Moses Roper from American Slavery states early in his disturbingly graphic portrayal of man’s inhumanity to man. One reason why Roper’s Narrative was so widely read in England and America after its initial appearance in 1837 is its unprecedented candor about the evils of slavery. The few autobiographical accounts of slavery before Roper’s call slavery unjust but rarely document its violation of the slave’s body and mind, as well as his rights as a human being. Roper’s Narrative, by contrast, demanded the attention of readers on both sides of the Atlantic because of its author’s exceptionally detailed and yet curiously deadpan accounts of the violence inflicted on him by his masters. Two distinguishing characteristics of Roper emerge, both of which seem to have aroused slaveholders to special viciousness toward him: his light skin and his incorrigible determination to escape. Roper’s Narrative contains perhaps the earliest accounts of racial passing in African American literature. Roper’s thrilling stories of his repeated escape attempts anticipate what made the fugitive slave narrative, later popularized by Frederick Douglass and William Wells Brown, one of the most widely read forms of autobiography in mid-nineteenth-century America.

Moses Roper was born in 1815 in Caswell County, North Carolina, on a plantation belonging to a man sometimes identified as John Farley. His mother, Nancy, was a slave on the plantation; his father, Henry Roper, was Farley’s son-in-law. At the age of six, Moses was sold away from his mother. Over the next fourteen years he passed through the hands of at least fifteen different owners and traders in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. The child of a mother who was, according to Roper, “part Indian and part African” and a father who was fully white, Roper was often mistaken for white, which presented a great handicap for him in slavery. However, during his escapes he used his appearance to his advantage by passing for a white traveler when the opportunity arose. The brutality he endured as a slave motivated Roper to make numerous escape attempts, which began when he was thirteen and ended only when he successfully fled the South in 1834. After fifteen months of insecure freedom in the North, Roper left the United States for England in November 1835.

In England, Roper was warmly received by the white abolitionist community, whose members helped him attend school and find work. Here he began to deliver lectures about his experience on behalf of antislavery efforts. Encouraged by his antislavery sponsors, Roper produced his Narrative, apparently his only publication, when he was twenty-one years old. Published in London and Philadelphia, the Narrative went through ten editions between 1837 and 1856, and was translated into Celtic.

In the original publication of the Narrative, Rev. Thomas Price, one of Roper’s British sponsors, explicitly dismisses any fears that the Narrative might have been written or heavily edited by Roper’s white supporters. Price states that Roper had “drawn up the following narrative” and it was “his own production.” In later editions, including the 1848 version reprinted here, Roper testifies to his authorial independence by dispensing with prefatory authentication by prominent whites in favor of composing his own preface. Roper did not abandon the text of his original Narrative in the later editions, another sign that he was, as he and his sponsors claimed, the author of the Narrative from its beginning. The 1848 edition of Roper’s Narrative is, nevertheless, importantly different from the original edition, especially because of the explanatory notes Roper adds to his original text and because of the appendix that brings his life story up to the mid-1840s.

Little is known of Roper’s life after the 1848 edition of his autobiography appeared. We know he married an Englishwoman in 1839. After a failed attempt to become a missionary in Africa, he and his wife and small child moved to Canada. Beyond a trip to England to lecture in 1854, nothing further is known about Roper’s life or death.

Suggested Readings

Andrews, William L. To Tell a Free Story: The First Century of Afro-American Autobiography, 1760–1865. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986.

Bruce, Dickson D., Jr. The Origins of African American Literature 1680–1865. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001.

Finseth, Ian Frederick. Introduction to “The Narrative of the Adventures and Escape of Moses Roper from American Slavery.” In North Carolina Slave Narratives: The Lives of Moses Roper, Lunsford Lane, Moses Grandy, and Thomas H. Jones, edited by William L. Andrews, 23–34. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003. [Finseth’s introduction is the most extended critical treatment of the narrative.]

Foster, Frances Smith. Witnessing Slavery: The Development of Antebellum Slave Narratives. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1994.

Nichols, Charles H. Many Thousand Gone: The Ex-Slaves’ Account of Their Bondage and Their Freedom. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1963.

Roper, Moses. “Letter to the Committee of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society.” May 9, 1844. Available in electronic form through Documenting the American South, an electronic database sponsored by The Academic Affairs Library at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, <http://docsouth.unc.edu/roper/support3.html>.

———. “Speeches Delivered at Baptist Chapel, Devonshire Square, 26 May 1836 and at Finsbury Chapel, London, England, 30 May 1836.” Available in electronic form through Documenting the American South, an electronic database sponsored by The Academic Affairs Library at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, <http://docsouth.unc.edu/roper/support4.html>.

Starling, Marian Wilson. The Slave Narrative: Its Place in American History. Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press, 1988.

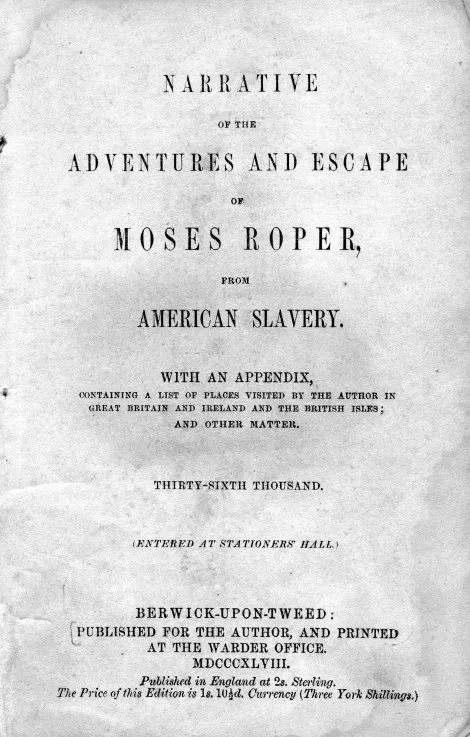

Note on the Text

The version of Moses Roper’s Narrative included here was published by Roper himself in England in 1848. This is the first time since its original publication that this edition has been reprinted. Although the most familiar versions of Roper’s Narrative are the first British and American editions, published in 1837 and 1838, respectively, the 1848 edition features more information about Roper’s life after his escape to England, and about the fates of several other enslaved persons mentioned in the Narrative. The 1848 edition also includes an appendix that briefly updates Roper’s life, a series of letters from readers debating the propriety of Roper’s escape, several poems penned by eager admirers, and a list of several hundred British churches Roper lectured in.

While this appended matter illustrates just how much Roper’s narrative and lectures captivated the British public in the early 1840s, in the interest of conciseness only the appendix updating Roper’s life has been reprinted in this volume. Interested readers can find the full text of the 1838 edition of Roper’s Narrative in William L. Andrews, ed., North Carolina Slave Narratives (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003). The entire 1848 edition, with all appended matter, is available online on Documenting the American South, http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/roper/menu.html.

References to page numbers in Roper’s notes to the 1848 edition of his Narrative have been changed to correspond to the pagination of this volume.

Title page of the 1848 edition of Moses Roper’s Narrative (Documenting the American South, <http://docsouth.unc.edu>, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries, North Carolina Collection)

NARRATIVE OF THE ADVENTURES AND ESCAPE OF MOSES ROPER, FROM AMERICAN SLAVERY. WITH AN APPENDIX, CONTAINING A LIST OF PLACES VISITED BY THE AUTHOR IN GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND AND THE BRITISH ISLES; AND OTHER MATTER.

Preface to the First Edition

The determination of laying this little narrative before the public, did not arise from any desire to make myself conspicuous, but with the view of exposing the cruel system of slavery, as will here be laid before my readers; from the urgent calls of nearly all the friends to whom I had related any part of my story, and also from the recommendation of anti-slavery meetings, which I have attended, through the suggestion of many warm friends of the cause of the oppressed.

The general narrative, I am aware, may seem to many of my readers, and especially to those who have not been before put in possession of the actual features of this accursed system, somewhat at variance with the dictates of humanity. But the facts related here do not come before the reader unsubstantiated by collateral evidence, nor highly coloured to the disadvantage of our cruel taskmasters.

My readers may be put in possession of facts respecting this system which equal in cruelty my own narrative, on an authority which may be investigated with the greatest satisfaction. Besides which, this little book will not be confined to a small circle of my own friends in London, or even in England. The slave-holder, the colonizationist, and even Mr. Gooch himself, will be able to obtain this document, and be at liberty to draw from it whatever they are honestly able, in order to set me down as the tool of a party. Yea, even Friend Brechenridge, a gentleman known at Glasgow, will be able to possess this, and to draw from it all the forcible arguments on his own side, which in his wisdom, honesty, and candour, he may be able to adduce.

The earnest wish to lay this narrative before my friends as an impartial statement of facts, has led me to develope some part of my conduct, which I now deeply deplore. The ignorance in which the poor slaves are kept by their masters, precludes almost the possibility of their being alive to any moral duties.

With these remarks, I leave the statement before the public. May this little volume be the instrument of opening the eyes of the ignorant of the system—of convincing the wicked, cruel, and hardened slaveholder—and of befriending generally the cause of oppressed humanity.

MOSES ROPER

LONDON, 1839.

LONDON, 1839.

NARRATIVE, &C. CHAPTER I

Birth-place of the Author.—The first time he was sold from his Mother, and passed through several other hands.

I was born in North Carolina, in Caswell County,1 I am not able to tell in what month or year. What I shall now relate, is what was told me by my mother and grandmother. A few months before I was born, my father2 married my mother’s young mistress. As soon as my father’s wife heard of my birth, she sent one of my mother’s sisters to see whether I was white or black, and when my aunt had seen me, she returned back as soon as she could, and told her mistress that I was white, and resembled Mr. Roper very much. Mr. Roper’s wife not being pleased with this report, she got a large club-stick and knife, and hastened to the place in which my mother was confined. She went into my mother’s room with a full intention to murder me with her knife and club, but as she was going to stick the knife into me, my grandmother happening to come in, caught the knife and saved my life. But as well as I can recollect from what my mother told me, my father sold her and myself, soon after her confinement. I cannot recollect anything that is worth notice till I was six or seven years of age. My mother being half white, and my father a white man, I was at that time very white. Soon after I was six or seven years of age, my mother’s old master died, that is, my father’s wife’s father.3 All his slaves had to be divided among the children.4 I have mentioned before of my father disposing of me; I am not sure whether he exchanged me and my mother for another slave or not, but think it very likely he did exchange me with one of his wife’s brothers or sisters, because I remember when my mother’s old master died, I was living with my father’s wife’s brother-in-law, whose name was Mr. Durham. My mother was drawn with the other slaves.

The way they divide their slaves is this: they write the names of different slaves on a small piece of paper, and put it into a box, and let them all draw. I think that Mr. Durham drew my mother, and Mr. Fowler drew me, so we were separated a considerable distance, I cannot say how far. My resembling my father so much, and being whiter than the other slaves, caused me to be soon sold to what they call a negro trader, who took me to the Southern States of America, several hundred miles from my mother. As well as I can recollect I was then about six years old. The trader, Mr. Mitchell, after travelling several hundred miles, and selling a good many of his slaves, found he could not sell me very well, (as I was so much whiter than other slaves were) for he had been trying several months—left me with a Mr. Sneed, who kept a large boarding-house, who took me to wait at table, and sell me if he could. I think I stayed with Mr. Sneed about a year, but he could not sell me. When Mr. Mitchell had sold his slaves, he went to the north, and brought up another drove, and returned to the south with them, and sent his son-in-law into Washington, in Georgia, after me; so he came and took me from Mr. Sneed, and met his father-in-law with me, in a town called Lancaster, with his drove of slaves. We stayed in Lancaster a week, because it was court week, and there were a great many people there, and it was a good opportunity for selling the slaves; and there he was enabled to sell me to a gentleman, Dr. Jones, who was both a Doctor and a Cotton Planter. He took me into his shop to beat up and mix medicines, which was not a very hard employment, but I did not keep it long, as the Doctor soon sent me to his cotton plantation, that I might be burnt darker by the sun. He sent me to be with a tailor to learn the trade, but the journeymen being white men, Mr. Bryant, the tailor, did not let me work in the shop; I cannot say whether it was the prejudice of his men in not wanting me to sit in the shop with them, or whether Mr. Bryant wanted to keep me about the house to do the domestic work, instead of teaching me the trade. After several months, my master came to know how I got on with the trade: I am not able to tell Mr. Bryant’s answer, but it was either that I could not learn, or that his journeymen were unwilling that I should sit in the shop with them. I was only once in the shop all the time I was there, and then only for an hour or two before his wife called me out to do some other work. So my master took me home, and as he was going to send a load of cotton to Camden, about forty miles distance, he sent me with the bales of cotton to be sold with it, where I was sold to a gentleman, named Allen...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- The North Carolina Roots of African American Literature

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Statement of Editorial Practice

- George Moses Horton, 1797

- David Walker, 1796–1830

- Moses Roper, 1815

- Lunsford Lane, 1803

- Harriet Ann Jacobs, 1813–1897

- Charles Waddell Chesnutt 1858–1932

- Anna Julia Cooper, 1858–1964

- David Bryant Fulton, 1863–1941

- Timeline