![]()

Chapter 1: Recruiting Women into the Cause

To Freedom’s cause, the cause of truth,

With joy we dedicate our youth.

To Freedom’s holy altar bring

Fortune and life as offering.1

When readers of the Liberator opened their newspaper one day in mid-August 1831, they discovered a fiery poem composed by a woman who identified herself only as a “female.” While the author did not explain what had prompted her to compose her verses and to submit them for publication, her outrage over slavery and her desire to compel others to acknowledge its evils hinted at the significant role women would play in the movement to eradicate American slavery.

Wake up, wake up, and be alive,

Let the subject of the day revive!

How can you sleep, how can you be at rest,

And never pity the oppressed.2

The woman’s urgent tone also indicated how drastically and rapidly the debate over American slavery was changing in the early 1830s. William Lloyd Garrison’s own interest in abolitionism dated back to an 1829 meeting with Benjamin Lundy, the Quaker editor of The Genius of Universal Emancipation. The Society of Friends had long opposed slavery and had pressed for gradual emancipation in the North. Now Lundy was advocating gradual emancipation and voluntary colonization as the twin strategies for ending American slavery in the South. When Garrison moved to Baltimore to work with Lundy on his newspaper, however, he discovered that the free black community in that city, as elsewhere, rejected colonization. Their influence transformed his thinking. By 1831, Garrison was espousing a platform of immediate uncompensated emancipation and publicizing the program in the pages of his Boston paper, the Liberator. Within a few years, Lundy would adopt Garrison’s view that colonization was “totally inadequate to abolition.”3

Garrison did not invent the idea of immediate emancipation, nor did he provide a clear definition of its meaning. The slogan “immediate emancipation” made the simple point that the work to end slavery must begin at once. Furthermore, the phrase suggested a dramatic break between modern Garrisonian abolitionism and previous efforts to abolish American slavery.4 Half a century earlier, opponents of slavery had hopes of gradually eliminating the institution so contrary to republican and revolutionary ideals. For several decades there were signs of progress. Methodist, Presbyterian, and Baptist ministers denounced slavery as a sin, and northern states, one by one, made slavery illegal. Quakers, recently forbidden to hold slaves, manumitted hundreds in Maryland and North Carolina. Even southern planters, particularly in the Upper South, where tobacco had worn out the land, emancipated their slaves in the 1780s and early 1790s. By 1810, more than 100,000 free blacks lived in the South, evidence of the scope of manumission in that region. Finally, in 1807, the infamous international slave trade, at least legally, came to an end.5

Whatever enthusiasm existed for ridding the nation of slavery faded rapidly in the early decades of the nineteenth century. In the South, the development of the cotton gin opened lucrative new possibilities for the region’s economy and encouraged the expansion of the plantation system. In the Upper South, breeding slaves for the internal slave trade cemented loyalty to the institution once seen as moribund. By the time of the debate over the Missouri Compromise, it was clear that southerners had a vigorous attachment to slavery and were prepared to defend it as a positive good. Bargains struck during the Constitutional Convention such as assigning to the federal government the responsibility for crushing slave insurrections offered powerful protections for the rejuvenated slave system.6

Still, antislavery sentiment did not disappear. In 1816, a Presbyterian minister from New Jersey established the American Colonization Society (ACS). As the organization’s name suggests, one of its primary goals was to send American free blacks back to Africa as colonists. This proposal appealed to conservative southern slaveholders who believed free blacks threatened the slave system and attracted those who wanted to rid the United States of its black population. Evangelicals, hopeful that former American slaves might convert the “pagan” Africans to Christianity, also supported the Colonization Society. Most free blacks had little interest in the scheme, however, and very few agreed to emigrate. By 1830, the ACS had transported only 1,420 African Americans to Liberia.7

The American Colonization Society’s second goal, gradual emancipation, was as far from realization as its first. The idea that slaveholders would, over time, voluntarily emancipate their slaves if they could all be sent off to Africa was flawed. But many northerners clung to the ACS because its program held out the possibility that eventually slavery might be ended without ruinous consequences for the country. During the 1820s, prominent evangelical laymen, well-known clergy, and well-known national politicians all endorsed the ACS and its agenda.8

Like black abolitionists who had rejected colonization out of hand in the mid-1820s, Garrison now condemned the ACS’s approach. The organization, he pointed out, did not regard slaveholding as a sin, and its attempt to rid the country of blacks revealed its prejudice against people of color. Garrison’s demand for immediate emancipation in the first issue of the Liberator in January 1831 represented the first salvo in his campaign against the ACS and its program. Ironically enough, Garrison had already hinted at his future position in an 1829 lecture delivered to the ACS in Boston’s Park Street Church. Slavery, he had declared on that occasion, was barbarous, despotic, and difficult to dislodge. Efforts to do so would require “a struggle with the worst passions of human nature,” but that struggle must begin at once. Antislavery demanded action. The “cause… would be dishonored and betrayed,” he argued, “if I contented myself with appealing only to the understanding.” Such an approach was “too cold and its processes are too slow for the occasion.” Barbarous, despotic, difficult to dislodge—slavery was all of these. But most important, slavery was a sin, not just for the slaveowner but for all Americans. It was a “national sin,” Garrison insisted, and one of which “we are all alike guilty.”9 The Liberator’s anonymous female poet had been less sweeping in assigning guilt, but she shared Garrison’s understanding of the moral universe. To the slaveholder, she issued a warning:

“Repent, repent, for you must die!

O, be admonished—turn and live.”10

While most evangelical Protestants ignored Garrison’s program of immediate emancipation, his identification of slavery as a sin that implicated all Americans grew out of an evangelical cultural perspective that provided a powerful moral and emotional context for abolitionism. Slavery was not just a flawed economic and social system. It was a moral transgression that could no longer be tolerated. The call to action that Garrison issued echoed the summons to repentance and a new life of active Christian commitment that had been sounded repeatedly in the Northeast since the 1820s. During the revivals of the Second Great Awakening, Protestant clergy had skillfully used an array of emotional techniques to stir up members of their churches to acknowledge their sinfulness and to turn to Christ. But conversion was not the final destination so much as it was the beginning of a new life. God, the pious believed, demanded more than a cultivation of the individual soul; those who had accepted Christ must struggle against sin. The converted Christian, disciplined against unseemly passions and committed to benevolence, should commence a new life in the world. Garrison’s definition of slavery as a heinous sin (caused by the slaveholder’s lust and self-indulgence) was capable of motivating evangelical Christians to action and could appeal to those, like Unitarians, who believed in the importance of good works in the world.11

Some members of the Society of Friends, whose historical and religious experiences differed dramatically from those of evangelical Protestants, also found Garrison’s analysis convincing. The Quakers had adopted a forceful stand against slavery during the eighteenth century, refusing slaveholders membership, taking the lead in early abolitionist organizations like the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, and fostering the education of free blacks. Friends were no longer in the forefront of antislavery by the time Garrison announced his program of immediate emancipation. The Pennsylvania Abolition Society, for example, supported gradual change through political channels and focused more on assisting free blacks than on freeing slaves in the South. But the Quaker belief in the Inner Light that revealed what had to be done in this life to gain salvation in the next could prompt a commitment to immediatism. Although the guidance of the Inner Light became clear only over time, the emphasis on doing one’s duty in the world did not differ so much from the compulsion that the climactic event of an evangelical conversion might unleash.12

In the late 1820s, controversies over the Inner Light and antislavery contributed to a division in the Society of Friends. Hicksites (the followers of Elias Hicks) laid more emphasis on the importance of the Inner Light and antislavery measures like the avoidance of slave products than Orthodox Friends. Orthodox Friends did became Garrisonians, but Hicksites were most responsive to Garrison’s program of immediate emancipation. One scholar has suggested that the division offered Hicksite women leadership opportunities that could promote social activism. In advocating the Hicksite position before members of the local and more distant meetings, women participated in debates crucial to the Society’s future and gained a heightened sense of female importance and equality. This self-confidence allowed some of them eventually to move into reform causes, whether or not more conservative Friends approved.13

While Garrison’s speech before the ACS did not represent any fully developed plan for ridding the nation of slavery, the definition of women as moral guardians of nineteenth-century society and culture implied some female role in antislavery activities. In his address, Garrison encouraged women to join with their congregations in pouring out “supplication[s] to heaven on behalf of the slaves.” Acknowledging three decades of women’s involvement in organized charitable and benevolent work, he also recommended that women work within the framework of “charitable associations to relieve the degraded of their sex.”14

When Garrison formally launched his antislavery effort in January 1831, he had given little further thought as to how women might contribute to the cause. Female readers, as his paper pointed out, could and should “fall upon… [their] knees, and lift up… [their] voices to heaven for those who are in bondage.” Early children’s stories in the Liberator also depicted parents instructing their children about slavery’s evils and indicated that, at this early point, Garrison and others visualized abolitionist women’s commitment as primarily domestic and familial. The belief that mothers were uniquely placed to shape children’s thinking was so central to the way middle-class northerners thought about motherhood that this emphasis never disappeared, even when other possibilities for female participation emerged. As one abolitionist paper explained at the end of the decade, the mother who read antislavery stories to her children began the process of making an abolitionist. “The child of two or three years will be more interested in the story of the poor slave, than with the whole Catalogue of Nursery tales.”15

In January 1832, Garrison, impressed by the antislavery work of British women, established a Ladies’ Department in his paper. This new feature, he hoped, would add to the interest women felt in the Liberator and “give a new impetus to the cause of emancipation.” Assuming that women needed encouragement, even though some were already contributing to his paper, he pointed out that a million enslaved women “ought to excite the sympathy and indignation of American women.” Attracting female support was hardly his most important priority, however. Because his ideas about the scope of female activism were still vague, his paper continued to propose the most obvious and least controversial possibilities. No doubt, the early emphasis on using nonslave products stemmed partly from the fact that “females who are interesting themselves in behalf of the poor slaves” could and already were acting upon their commitments at home. The Liberator’s anonymous poet had asked her readers:

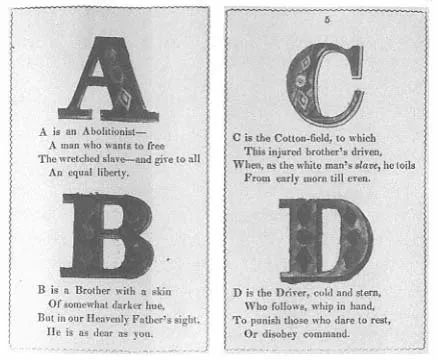

This alphabet, aimed at bringing the antislavery message to children, is an example of the continuing interest in converting children to abolitionism within the confines of the home. (Boston Athenœum)

“How can you eat, how can you drink,

How wear your finery, and ne’er think

Of those poor souls, in bondage held,

Whose painful labor is compelled?

The implied response was that no true Christian, and certainly not a woman, could fail to understand the relationship between the articles of daily life and slavery. Domestic life could not continue as usual.16

A letter published in 1832, ostensibly from “a plain hardworking farmer,” showed the internal ramifications of adopting free-labor principles. The farmer pictured his family in the midst of a domestic transformation in which women took the lead. “My wife and grown up daughters,” he wrote, “have got a notion out of some tract they have been reading, that we ought not to eat rice, nor sugar, nor anything that is raised by the labor of slaves.” Using the Liberator as her guide, his daughter had quizzed him about free and slave products. As she finished her list of questions, she announced triumphantly, “‘I am sure you will think just as we do.’”17

Boycotting goods not only drew upon impeccable historical precedents—in particular, the activities of women during the American Revolution—but it also accorded with the nineteenth-century view of women as unselfish, practiced in self-denial, and morally insightful. The practice was firmly rooted in the new realities of economic life. Although the plain and hardworking farmer still went to town for household supplies, in many middle-class households women were in the position to make or at least to influence consumption decisions.

The idea of boycotting products produced by slave labor also built upon Quaker principles and organizational efforts. Quaker leaders, including Elias Hicks, had urged Friends to use only “free” goods. In the late 1820s, associations pledged to the free produce principle were established in several cities with substantial Quaker communities. Black women belonging to Philadelphia’s Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church also established their own free produce association in 1829. Several of these women would later become active in the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFAS).18

The fact that women who abhorred slavery formed the backbone of the early free produce movement doubtless prompted Garrison to urge female sympathizers to form free produce societies and patronize shopkeepers like Lydia White, an African American, who ran a dry goods store in Philadelphia that carried products of free labor. As the newspaper pointed out, women outside of Philadelphia could take advantage of her store: White took orders from states as distant as Vermont, Indiana, and Ohio.19

The hardworking farmer had raised the question of just how the efforts of one family might contribute to the demise of slavery. Theoretically, the boycott could undermine the market for slave products and goods made from them, thus undermi...