![]()

Chapter 1

THE CAFÉS OF VIENNA

Space and Sociability

Charlotte Ashby

In every large or small town throughout the Habsburg lands there is a Viennese coffeehouse. In it can be found marble tables, bentwood chairs and seating booths with leather covers and plush upholstery. In bent-cane newspaper-holders the Neue Freie Presse hangs among the local papers on the wall … Behind the counter sits the voluptuous and coiffured cashier. Near her looms the expressionless face of the head waiter, who as soon as the call ‘Herr Ober, the bill!’ is issued, will vanish from the guest’s field of vision. The barman lurks casually, but jumps to attention readily enough, though at no time giving the impression of hurried bustle. All in good time, the junior waiter brings the quietly clinking metal tray with its full glass of water to your table. One orders the coffee by means of a secret language that no one from outside the country understands: ‘eine Melange mehr licht’, ‘eine Teeschale Braun’, ‘eine Schale Geld passiert’.1

This evocative picture of the classic Viennese café can be found replicated in multiple histories, memoirs, biographies and works of fiction that focus on Vienna of the late nineteenth century. This quotation captures the affection and nostalgia which has long coloured any consideration, academic or otherwise, of the Viennese café. The image evoked, of the marble table tops, bent-wood chairs, multiple newspapers and idiosyncratic staff, is one that has become something of a legend. The distillation of the one thousand or so coffeehouses there were in Vienna around 1900 into a single image obscures the multiplicity and complexity of this particular space-type within the city.2 This chapter will introduce the cafés of Vienna as a social space in the city and the role they played in the city’s social and cultural life. A historical account of the role of the cafés is difficult to establish because, for the most part, it requires delving into the ephemeral realm of the everyday life and habits of the people of Vienna. This life was essentially transitory and casual in nature and as such proves resistant to recording and documentation. Various opportunities for excavating the ephemeral do however exist. A number of the cafés themselves survive, in a more or less altered state, as a material record of these spaces. Visual records – photographs, drawings, paintings and postcards – can also offer a window onto the nature of these spaces and the society within. In addition, literary sources, such as fiction, travel writing, biography and autobiography, provide another perspective on how the cafés of Vienna were used and regarded by contemporaries.

The importance of the cafés as part of the ‘story’ of Vienna 1900 is not simply a nostalgic construction following the Second World War. The café was the foremost public social institution within the city. Unlike the theatre or the opera house, the café could be visited every day and at virtually any time of day. The proliferation of cafés through the city indicates that they were a regular feature in the lives of many Viennese. The café appeared as a location in novels and other literary works of the period.3 Guide books in both English and German all make particular reference to the cafés of the city, exclaiming on their numerousness and the quality of the service.4 As a ubiquitous feature of city life, the café was multifarious in its provision of services to people of different classes and genders. The ephemeral nature of the sociability it played host to continues to make it difficult to categorise, in its close relation to the complex identity of the city at the dawn of the twentieth century.

The Café and its Relation to High and Low Culture

The relationship of cafés to the development of cultural life is well established. Jürgen Habermas presented the coffeehouses of eighteenth-century London as the crucibles for the formation of a bourgeois public sphere in England.5 These cafés provided a space for an active public of private individuals with shared concerns to come together and create shared discourse. The printed word made a vital contribution to the establishment, through the practices of criticism and critical debate, of the realm of public discourse:

The predominance of the ‘town’ was strengthened by new institutions that, for all their variety, in Great Britain and France took over the same social functions: the coffeehouses in their golden age between 1680 and 1730 and the salons in the period between the regency and the revolution. In both countries they were centres of criticism – literary at first, then also political – in which began to emerge, between aristocratic society and bourgeois intellectuals, a certain parity of the educated.6

Habermas’ thesis maintained that this public sphere declined in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries into a passive culture of mass consumption rather than public discourse. This decline was engendered by the growth in the number of people who constituted the public until its unity, as a single public, was impossible to sustain.7 Within Habermas’ thesis the development of the practice of voicing public opinion spread from the arena of literature naturally into matters of political and public interest, engendering the development of a sphere in which all matters of public interest could be discussed and new ideas formulated.

Habermas’ theory cannot be applied seamlessly to the role of the café in Vienna. For one thing, prior to 1848, prohibitions on the expression of political opinions, together with the lack of a democratic framework of any kind in which such opinions could carry weight, made the development of a public sphere of the kind evoked by Habermas largely impossible. By the late nineteenth century, when the cafés of Vienna had become sites of intense public discourse, both literary and political, the onset of mass culture, presented by Habermas as the antithesis of the public sphere, was also well under way. The Viennese café is thus a site in which the development of a public sphere is both delayed and complicated by its chronological compression. By looking at the points at which the Viennese café does and does not conform to the outline of public space and public sphere developed by Habermas, we can build a clearer picture of the way in which the café contributed to the life of the city.

The Café as a Site of Leisure

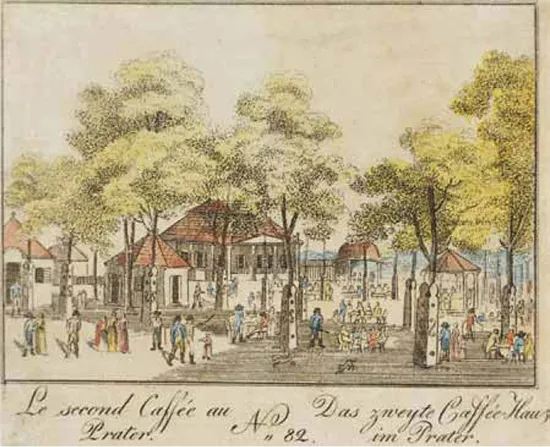

Habermas’ assessment of the rise of popular mass culture at the end of the nineteenth century was couched in terms of the fracturing and decline of the public sphere, as culture and ideas were packaged for consumption rather than evolving through rational debate. This view, however, sets up an artificial dichotomy between high and low culture, the serious and the frivolous, which obscures the essence of the cafés as institutions straddling both professional and recreational spheres. The café’s function as leisure venue was an established part of its identity as a public space. The link between recreation and café culture in the city of Vienna goes back to the eighteenth century. The Prater Park had been opened to the people of Vienna by Josef II in 1766 and the first café, the Erste Café, opened in the Prater in 1787. The Zweite Café followed in 1799 (Figure 1.1). Lithographic topographies of the city in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries frequently show such outdoor cafés, either those on the Prater or overlooking the city bastions. Such scenes indicate the ubiquity of these cafés as social spaces around the city. The stroll in the park, the promenade on the bastion and later the Ringstrasse, and the visit to the café were intimately woven into the pattern of Viennese leisure habits from the late eighteenth century onwards. Though the majority of cafés did not provide elaborate entertainments until the late nineteenth century, their offerings of refreshments, relaxed ambiance and table-top games were enough of a draw to make them prime sites for recreation in the city. For the bourgeoisie in particular, the cafés of the city centre and wealthy suburbs provided a well-loved and regularly used space outside of the home for informal, primarily but not exclusively masculine socialising and private relaxation. The precise nature of this sociability will be discussed further on in this essay.

Figure 1.1 The Zweite Café on the Prater, c.1820. Courtesy of the Wien Museum.

The café’s function as a place where people went to relax and as a site of urban leisure is not an aspect that can be filtered out of any discussion of its role. By the late nineteenth century the growth of mass media, the entertainment industry and the advent of party politics, all of which Habermas viewed as sounding the death knell to true public discourse, was well under way even in Vienna. Within the supposed decline of the public sphere the only roles left for cafés to play would have been either as venues of popular entertainment or as retreats for an elite intellectual culture, divorced from public relevance. The growth of the large-scale entertainment cafés in Vienna from the 1870s confirms the idea of the rise of mass culture. From relatively simple establishments serving coffee and various other beverages, tobacco, simple snacks and table-top games, cafés expanded in the nineteenth century to take advantage of the growing wealth of the urban middle classes and the entertainment industry was born. Grand entertainment establishments in new hotels, in city parks and new bourgeois suburbs took the basic idea of a café and extended it to include more elaborate forms of entertainment.

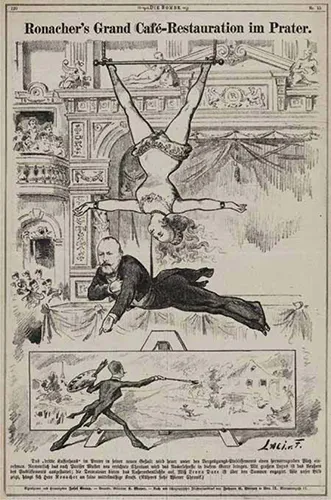

The new hotels built in expectation of the crowds attending the 1873 World’s Fair in Vienna all included extensive café spaces on the ground floor of their premises. Prasch’s Café and Billiard Hall, on the Wienzeile, which first opened in 1851, offered extensive recreational facilities, including multiple games rooms, a concert hall, a reading room, a refreshment room and conservatories.8 Café Volksgarten, in the city centre, offered a fine restaurant and outdoor concerts in the smartest park in the city. The Prater Park, with its long history as a centre for recreation, developed to include various amusements, such as the ‘Venice in Vienna’ attraction, opened in 1895, and the Ferris wheel completed in 1897. The Café Dritte, originally established in the Prater Park in 1802, was refurbished in time for the World’s Fair, expanding on the idea of the concert-café to become a café and variety theatre with a capacity for 5000.9 Although the World’s Fair proved to be something of a flop, the café was bought up by Anton Ronacher and became a huge success, showing musical comedies, operettas and other stage acts (Figure 1.2). Much of the expansion of the entertainment industry in the late nineteenth century was undertaken under the auspices of the café, as an established leisure-venue type. The large entertainment cafés did not, therefore, represent an overturning of a more worthy, intellectual and politicised café space, but rather an elaboration on one ongoing aspect of the identity of the Viennese café.

The Biedermeier Café

Alongside the identity of the Viennese café as a leisure destination, its role as a centre of cultural life was also a well-established facet of its popular identity. In the late nineteenth century in particular, the café society of the early nineteenth century was celebrated nostalgically as an emblem of the past cultural and intellectual achievements of the city. This so-called ‘Biedermeier period’ was regarded by many as the pinnacle of good taste and authentic Viennese brilliance, from which modern culture had sadly declined.10 Adolf Loos’s design for the Café Museum of 1899 was a conscious attempt to revive the atmosphere and ambience of a Biedermeier café. The image of the Biedermeier café incorporated within it a suggestion of vibrant intellectual and creative discourse followed by the city at large, and is analogous with Habermas’ bourgeois public sphere.

Figure 1.2 Laszlo Frecskay, Ronacher’s Grand Café in the Prater, 1879. Courtesy of the Wien Museum.

The Biedermeier café was a public sphere in the sense that it provided a centre for the communication and propagation of new ideas. However, as its purview was limited to the arena of culture and aesthetics, its development was stunted in relation to the development from a cultural discourse of literary cr...