![]()

Part I

Imaginaries of Peoples

![]()

Chapter 1

Toward Symmetric Treatment of Imaginaries

Nudity and Payment in Tourism to Papua’s “Treehouse People”

Rupert Stasch

This chapter seeks to advance the study of the imaginaries that structure cultural tourism by arguing for symmetric attention to perspectives of tourists and visited people. Such symmetry brings out more sharply what tourism imaginaries are, and what they do. I argue for such an approach through the example of encounters between international tourists and Korowai of Papua, Indonesia. My specific focus is exoticizing stereotypes that Korowai and tourists hold about each other, and these stereotypes’ expression in concrete actions.

There are several levels to symmetry’s value. One is that by juxtaposing different populations’ stereotypy, each side’s ideas stand out more sharply as imaginative. Putting different participants’ models side by side highlights how “out of touch” each group is with the other’s actual subjectivity, and thus how much the exoticizing stereotypy exists as a collective representation with a life of its own among the stereotypers. At the same time, this juxtaposition underscores similarities between different sides’ processes of exoticization. We will see that Korowai and tourists stereotype each other in similar ways, without knowing it. This too throws into relief how much each side’s stereotypy is an imaginative projection grounded in the lives of the stereotypers themselves and conditions of the tourism encounter.

Besides making imaginaries stand out more sharply, symmetry also helps us better discern the actual organization of tourism interactions as structures of “working misunderstanding” (Dorward 1974). When people relate closely across cultural disparities, all participants’ imaginaries shape the articulations that emerge. I document here tourist and Korowai imaginaries’ force in conditioning their perceptions and actions, but I also explore how articulations between Korowai and tourists are influenced by their imaginaries’ openness and heterogeneity. Patterns of coordination across gulfs of mutual incomprehension depend not only on imaginaries’ projective constraining of experience and practice, but also on their ambiguous character of pointing to possibilities other than themselves.

The empirical value of studying all participants’ perspectives might seem obvious, but commitment to such an approach is still emerging in tourism studies and in the study of intersocietal articulations generally. There is a metatheoretical level to symmetry’s value, having to do with the covert and lopsided power of the imaginaries of tourists on the intellectual horizons of tourism scholars. Analysis of tourism can easily be swayed by dominant ideological precepts of tourists’ home societies, such as the idea of a fundamental difference of being between tourists and the people they visit, or the idea that the social position of tourist is false or immoral. I take up this theme in my conclusion, where I discuss the importance of the recent transition toward symmetry in the anthropology of tourism, within concern with symmetry in the cultural sciences generally.

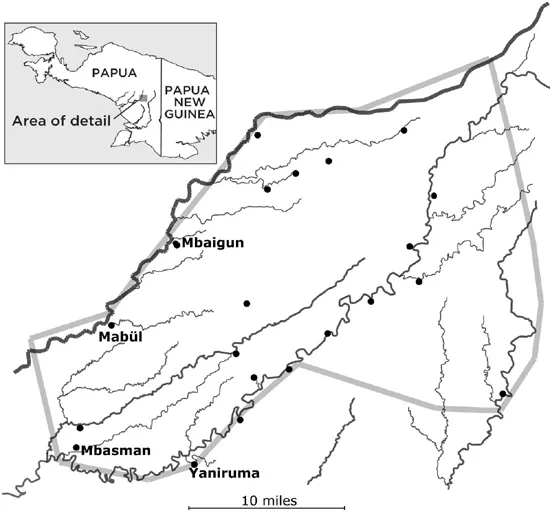

AN OVERVIEW OF KOROWAI TOURISM

About four thousand Korowai live spread across five hundred square miles of forest in the southern lowlands of Papua, where they make their livelihoods by tending sago stands and banana gardens, as well as by fishing and hunting (figure 1.1). All their activities are shaped by high valuing of kinship and social bonds on the one hand, and high valuing of autonomy and equality on the other (Stasch 2009). This contradictory mix of values is reflected in people’s practices of living far apart to avoid subjection to each other’s wills, while also traveling constantly in pursuit of social connections. The overall landscape is a patchwork of forest territories each about one square mile in expanse, owned by different patriclans. In the past, people were only comfortable living on their own land or that of close relatives. Today this practice of living far apart coexists with residence in centralized villages. Village creation began in 1980 with the opening of the airstrip settlement of Yaniruma by Dutch missionaries. The missionaries left in 1991, but Korowai have continued to form new villages on their own initiative (shown by dots in figure 1.1). Roughly one-third of Korowai live in villages, one-third live on forest land, and one-third continuously alternate back and forth between both types of space (Stasch 2013). Until recently, the Indonesian government was an even more distant presence than church organizations. Korowai themselves have actively fashioned their modes of engagement with the wider state, market, and religious institutions they now know themselves to live amidst (Stasch 2001, 2014).

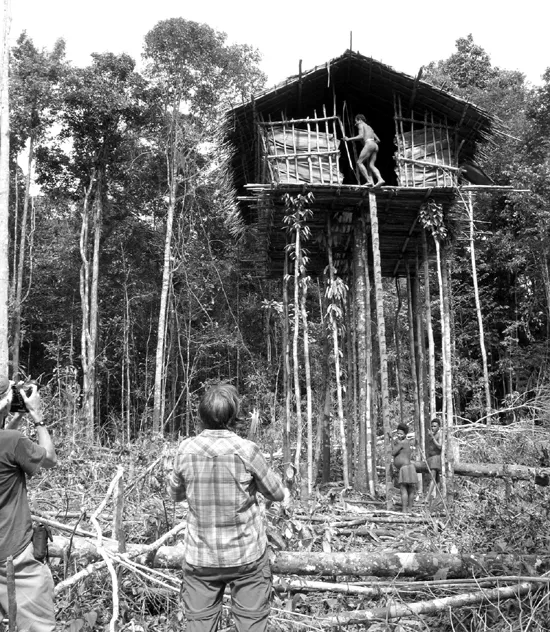

What Korowai are famous for internationally is their “treehouse” architecture. For over twenty years, international tourists and media professionals have been drawn to the area by these treehouses and by a further range of ways Korowai are thought to exemplify a condition of primitiveness and purity (figure 1.2). Tourist visits to the Korowai area began around 1990, first with brief visits by longboat to the far southwest corner of the Korowai lands, and later by chartered Cessna flights to Yaniruma. Overall, about five thousand tourists have visited Korowai or their closely related Kombai neighbors across recent decades. This is small even by comparison to the modest scale of arrivals in Papua’s other main destinations, such as the Baliem Valley, the Asmat coast, and the Raja Ampat Islands. At the peak around 1997, several hundred tourists visited each year. But the more typical pattern has been for many months to pass with no visitors, followed perhaps by a burst of several groups in a few weeks. Growth in visitors has been inhibited by Papua’s limited tourism infrastructure more generally, by political and military conflict surrounding Papuan desires to be an independent country, by wider ethnoreligious violence in Indonesia in the late 1990s, by the cessation of direct flights from Los Angeles to Papua in 1998, by the World Trade Center attack and Bali bombings in the early 2000s, and by the 2008 global economic downturn. Arrivals have also been constrained by the extremely high cost of plane or boat charters now needed to reach gateway villages on the edges of the Korowai lands.

Figure 1.1. Korowai lands in Papua. Tourists arrive by longboat or airplane at the four villages with their names shown (Copyright: R. Stasch).

Figure 1.2. Members of a German tour group photographing the house of Saxip Bumxai (Copyright: R. Stasch).

Many visitors are highly educated professionals, and some are quite affluent. They include citizens of almost every European country and most settler colonial ones. In the 1990s, German and US nationals accounted for half of travelers, reflecting primitivism’s special strength in Germany and the large size of the US traveling population. US tourists dropped away in the 2000s, while citizens of ex-Soviet bloc countries are now prominent. The median size of groups is four persons, and the maximum is about twelve. The destination’s high costs, combined with its reputation for true primitivity, have meant that large portions of visitors are filmmakers and other media professionals (Stasch 2011a, 2011b).

Once they arrive at villages in the southwest, tourists set out on foot with local porters to visit Korowai living in treehouses on their forested clan lands. These treks last between one and ten days, and include events of Korowai performing subsistence activities for the groups. Some groups witness culminating stages of a sago grub feast, staying in housing built for them in advance at the feast site. Tourists are usually accompanied by a paid Indonesian or Papuan guide, who communicates with them in English. Most guides live near Jayapura on Papua’s north coast, which tourists transit through on their flights from Bali or Jakarta. In the costliest packages, the guide works for an international tour leader who also accompanies the group.

Alongside communicating in English with clients, guides speak Indonesian with some Korowai (Stasch 2007). In particular, guides work closely with specific Korowai men who are established tourism specialists. These mediators translate in turn between Indonesian and Korowai, to convey visitors’ desires to other Korowai. The overall situation is thus one of Korowai talking densely with each other in their vernacular, tourists likewise talking densely with each other in their home language, and a bottleneck of multistep translation between these groups via a small number of intermediaries.

This linguistic situation is one reason why tourist and Korowai ideas about each other circulate much more densely within each population than between them, even when the two groups are in each other’s presence. Moreover, long before and after their direct interactions, Korowai and tourists alike devote much attention to the idea of the other. A core paradox of their relation is that both groups care intensely about their meetings, but each is mostly oblivious of the others’ understandings. Their representations of the other have a life of their own, grounded less in actual characteristics of the stereotyped people than in sociocultural and psychological conditions of the stereotypers themselves, or conditions of their meetings.

This is one reason the concept of tourism imaginaries is relevant to the encounters. Scholars have used the noun “imaginary” to mean different things (bearing a variety of ambiguous relations to alternatives such as “culture” or “semiotic order”). Yet many uses have in common that they fuse two streams of thought about human consciousness: first, social scientists’ sensitivity to collective process and the world-constituting effects of ideas (e.g., Castoriadis [1975] 1987; Taylor 2004); and second, philosophers’ and psychoanalytic theorists’ sensitivity to the complex creativity and multiplicity of individual subjective makeup (e.g., philosophical ideas about “imagination” as interior faculty surveyed in Kearney [1988, 1991]). Such a fusion is well suited to thinking about Korowai and tourists’ highly creative and projective images about each other.

TOURIST IMAGINARIES ABOUT KOROWAI

I already noted that tourists’ travel is motivated by a notion that Korowai instantiate a condition of primitive humanity. In other words, their visits to Korowai flow from the vast cultural formation of contemporary global primitivism. Primitivism is any body of ideas in which one set of people imagines another as archaic, not simply in time of actual living but in ontological time: their very being is tied to an earlier epoch. This idea is expressed, for example, in one US economist’s diary entry recounting a feast on the Kombai-Korowai borderlands, posted on his consulting firm’s website:

In primitivist tourism of this kind, metropolitan travelers visit people understood to be original and basic, to experience their complexly admired, disparaged, and exoticized cultural attributes. The travelers describe their cosmos as consisting of a Manichaean polarity of two types of humanity, the civilized and the primitive (not always labeled by these specific terms). This model’s core contrast of contemporaneity versus archaicness is also intertwined with an understanding that the civilized pole is economically and technologically more powerful than the primitive, and a threat to its existence. Yet primitive humanity is superior to the civilized in morality, ecology, and aesthetics. It is a source of redemption or pleasure for inhabitants of civilization, while also being linked to fearful and inferiority-marked practices like cannibalism.2 Primitivist ideas are familiar to tourism scholars from the documentary Cannibal Tours (O’Rourke 1987) and from early studies by Cohen (1989) and Bruner and Kirshenblatt-Gimblett (1994), as well as from blockbuster films like Avatar, Dances with Wolves, and many other cultural artifacts. There is now a worldwide boom in this type of tourism, referred to in different national and academic spheres under such designations as “indigenous cultural tourism,” “Aboriginal tourism,” “first nations tourism,” “tribal tourism,” and tourism of “minority nationalities.”

That tourist imagery about Korowai has a life of its own is illustrated by certain words tourists apply to Korowai that do not fit their actual lives. Tourists commonly call specific old-looking Korowai men the “chief” of a group, even though Korowai do not recognize any such leadership roles or otherwise link adult age differences with authority. Tourists also routinely affirm that Korowai are “hunter-gatherers,” even though most of their food comes from gardens right below their houses and from carefully managed sago groves. Often tourists call a Korowai feast compound or a garden clearing with two houses a “village,” even though there were historically no Korowai words for “village” and no actual permanent settlements. These and other features of tourist discourse reflect a generic idea of primitive cultural others that preexists its application to Korowai.

Dozens of television shows and a hundred or more magazine and newspaper stories have played an important role in making Korowai iconic representatives of the idea of “Stone Age” existence in global primitivist imaginaries today. For example, in June 2009, five million French prime-time television viewers watched an episode of Rendez-vous en terre inconnue in which the pop singer Zazie was shown living in a Korowai household. A segment on Korowai treehouse building was featured as the culmination of the “Jungle” episode of the widely seen 2011 BBC and Discovery television series Human Planet. Articles about Korowai and Kombai have been published in such magazines as National Geographic, Reader’s Digest, Outside, Smithsonian, and The New Yorker. Photographs of Korowai are prominent in Sebastião Salgado’s recent Genesis exhibition and associated book (Salgado 2013), and numerous other travel books have been published detailing visits to them.

The market demand for these media products exemplifies the general pattern that international metropolitan audiences intensely value Korowai, and intensely value the idea of interaction with them across divides of radical difference. For tourists, a visit to Korowai has an aura of profound significance, as an enacted picture of the primitivist cosmos of two foundationally different kinds of humans (compare Adler 1989). MacCannell (1976) used the Goffman-derived contrast of “frontstage” and “backstage” to describe the general organization of tourism as a quest for authentic realities felt to lie behind regular-life appearances. Extending this metaphor, we could say that tourists understand Korowai trips as access to the backstage of humanity at large.

KOROWAI IMAGINARIES ABOUT TOURISTS: SIMILARITIES IN EACH SIDE’S STEREOTYPY

In the wake of studies by Said (1978), Todorov (1984), and others, it has become a common exercise for scholars to show that European or settler colonial exoticizing stereotypy about ethnic others is a representational system with logics of its own. My sketch of tourist primitivism above followed this pattern. Much rarer is detailed work on non-Westerners’ stereotypy about Westerners. From studies that do exist (e.g., Basso 1979; Bashkow 2006; Vilaça 2010), it is unsurprising that Korowai have elaborate ideas about foreigners. Sketching these ideas now, my concerns will be to establish that this stereotypy also has a life of its own among the stereotypers, and to note striking parallels between each side’s stereotypes.

For most Korowai, tourists have been a bigger presence than all other categories of radical strangers whom they have become newly concerned with across the last thirty-five years. Yet due to Korowai spatial dispersion, as well as the infrequency of tourist visits and the erraticness of where they go on the land, there are many Korowai who have never interacted with tourists or have met only one or two groups. However, talk about tourists circulates widely across the Korowai population, much as imagery about Korowai circulates widely in tourist-sending countries and is...