- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

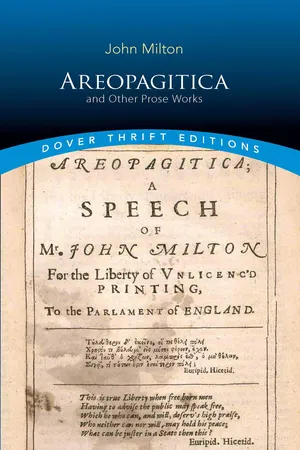

Areopagitica and Other Prose Works

About this book

An uncompromising defender of liberty as well as a sublime poet, John Milton published the "Areopagitica" in 1644, at the height of the English Civil War. The impetus arose from Parliament's Licensing Order, which censored all printed materials and ultimately led to arrests, book burnings, and other authoritarian abuses. Milton's polemic, strengthened by biblical and classical allusions, remains enduringly significant and ranks among the world's most eloquent defenses of the right to free speech.

In addition to the "Areopagitica," this collection of Milton's most significant prose works includes "Of Education," a tract on educational reform; "Meditation Upon Divine Justice and The Death of King Charles the First," a rationale for the overthrow of the monarchy; "The Doctrine and Disciple of Divorce," in which the author urges the enactment of a virtually unheard-of reform allowing divorce for incompatibility and the right of remarriage; and "Autobiographical Extracts," featuring highlights from Milton's memoirs.

In addition to the "Areopagitica," this collection of Milton's most significant prose works includes "Of Education," a tract on educational reform; "Meditation Upon Divine Justice and The Death of King Charles the First," a rationale for the overthrow of the monarchy; "The Doctrine and Disciple of Divorce," in which the author urges the enactment of a virtually unheard-of reform allowing divorce for incompatibility and the right of remarriage; and "Autobiographical Extracts," featuring highlights from Milton's memoirs.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Areopagitica and Other Prose Works by John Milton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophie & Europäische Literarische Sammlungen. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE DOCTRINE AND DISCIPLINE OF DIVORCE

RESTORED TO THE GOOD OF BOTH SEXES, FROM THE BONDAGE OF CANON LAW, AND OTHER MISTAKES, TO THE TRUE MEANING OF SCRIPTURE IN THE LAW AND GOSPEL COMPARED

WHEREIN ALSO ARE SET DOWN THE BAD CONSEQUENCES OF ABOLISHING, OR CONDEMNING AS SIN, THAT WHICH the LAW OF GOD ALLOWS, AND CHRIST ABOLISHED NOT

NOW THE SECOND TIME REVISED AND MUCH AUGMENTED IN TWO BOOKS

TO THE PARLIAMENT OF ENGLAND WITH THE ASSEMBLY

MATTH. xiii. 52. “Every scribe instructed in the kingdom of heaven is like the master of a house, which bringeth out of his treasury things new and old.”

PROV. xviii. 13. “He that answereth a matter before he heareth it, it is folly and shame unto him.”

[This great work on Divorce, with the three parasitical treatises, “Tetrachordon,” “The Opinions of Martin Bucer,” and “Colasterion,” may be said nearly to exhaust all the philosophy and learning of the subject.... It is to be regretted that Milton’s language should now, in course of time, have come to appear at first sight a little antiquated, which may discourage many from the study of this interesting and extraordinary work, in which nearly every question connected with marriage and divorce is discussed with surprising eloquence, learning, and freedom. To his own contemporaries his expressions, no doubt, appeared appropriate and perspicuous, though they now often seem vague and ill-selected, through the inevitable revolutions of language, which have stripped words of their old significations to attach to them others altogether new. Nevertheless, a moderate supply of patience will enable us to reconcile ourselves to his diction, and to that peremptory style of argumentation, which in an age of political excitement and fierce party struggles is naturally adopted by all earnest and energetic writers. In scriptural interpretation, he pushes the protestant licence to the utmost, arrays text against text, gospel against law, and law against gospel, and ultimately decides in conformity with the suggestions of reason. This in a person so strict and pious, is really a matter of astonishment. No man was ever more religious than Milton, but his religion was a pure transcendental philosophy, which soared above texts and formularies, and rested ultimately on the eternal relations subsisting between God and his creatures. In other respects these works on divorce are full of beauty, of poetical descriptions of love, of philosophical investigations, of original ideas and images. The whole is pervaded and adorned by an enthusiastic spirit of poetry which constitutes in him the vitality of style. All therefore who can tolerate a little quaintness and plain speaking, and who are not averse from being taught by a somewhat dogmatic instructor, can read with pleasure Milton’s speculations on divorce, which are full of sound wisdom which may serve to enlighten both our legislators and philosophers, if they will be modest enough to listen and learn.

J. A. ST. JOHN.]

TO THE PARLIAMENT OF ENGLAND, WITH THE ASSEMBLY

If it were seriously asked (and it would be no untimely question), renowned parliament, select assembly! who of all teachers and masters, that have ever taught, hath drawn the most disciples after him, both in religion and in manners? it might be not untruly answered, custom. Though virtue be commended for the most persuasive in her theory, and conscience in the plain demonstration of the spirit finds most evincing; yet whether it be the secret of divine will, or the original blindness we are born in, so it happens for the most part that custom still is silently received for the best instructor. Except it be, because her method is so glib and easy, in some manner like to that vision of Ezekiel rolling up her sudden book of implicit knowledge, for him that will to take and swallow down at pleasure; which proving but of bad nourishment in the concoction, as it was heedless in the devouring, puffs up unhealthily a certain big face of pretended learning, mistaken among credulous men for the wholesome habit of soundness and good constitution, but is indeed no other than that swoln visage of counterfeit knowledge and literature, which not only in private mars our education, but also in public is the common climber into every chair, where either religion is preached, or law reported; filling each estate of life and profession with abject and servile principles, depressing the high and heaven-born spirit of man far beneath the condition wherein either God created him, or sin hath sunk him. To pursue the allegory, custom being but a mere face, as echo is a mere voice, rests not in her unaccomplishment, until by secret inclination she accorporate herself with error, who being a blind and serpentine body without a head, willingly accepts what he wants, and supplies what her incompleteness went seeking. Hence it is, that error supports custom, custom countenances error; and these two between them would persecute and chase away all truth and solid wisdom out of human life, were it not that God, rather than man, once in many ages calls together the prudent and religious counsels of men, deputed to repress the incroachments, and to work off the inveterate blots and obscurities wrought upon our minds by the subtle insinuating of error and custom; who, with the numerous and vulgar train of their followers, make it their chief design to envy and cry down the industry of free reasoning, under the terms of humour and innovation; as if the womb of teeming truth were to be closed up, if she presume to bring forth aught that sorts not with their unchewed notions and suppositions, against which notorious injury and abuse of man’s free soul, to testify and oppose the utmost that study and true labour can attain, heretofore the incitement of men reputed grave hath led me among others; and now the duty and the right of an instructed Christian calls me through the chance of good or evil report, to be the sole advocate of a discountenanced truth: a high enterprise, lords and commons! a high enterprise and a hard, and such as every seventh son of a seventh son does not venture on. Nor have I amidst the clamour of so much envy and impertinence whither to appeal, but to the concourse of so much piety and wisdom here assembled. Bringing in my hands an ancient and most necessary, most charitable, and yet most injured statute of Moses: not repealed ever by him who only had the authority, but thrown aside with much inconsiderate neglect, under the rubbish of canonical ignorance; as once the whole law was by some such like conveyance in Josiah’s time. And he who shall endeavour the amendment of any old neglected grievance in church or state, or in the daily course of life, if he be gifted with abilities of mind, that may raise him to so high an undertaking, I grant he hath already much whereof not to repent him; yet let me aread him, not to be the foreman of any misjudged opinion, unless his resolutions be firmly seated in a square and constant mind, not conscious to itself of any deserved blame, and regardless of ungrounded suspicions. For this let him be sure, he shall be boarded presently by the ruder sort, but not by discreet and well-nurtured men, with a thousand idle descants and surmises. Who when they cannot confute the least joint or sinew of any passage in the book; yet God forbid that truth should be truth, because they have a boisterous conceit of some pretences in the writer. But were they not more busy and inquisitive than the apostle commends, they would hear him at least, “rejoicing so the truth be preached, whether of envy or other pretence whatsoever”: for truth is as impossible to be soiled by any outward touch, as the sunbeam; though this ill hap wait on her nativity, that she never comes into the world, but like a bastard, to the ignominy of him that brought her forth; till time, the midwife rather than the mother of truth, have washed and salted the infant, declared her legitimate, and churched the father of his young Minerva, from the needless causes of his purgation. Yourselves can best witness this, worthy patriots! and better will, no doubt, hereafter: for who among ye of the foremost that have travailed in her behalf to the good of church or state, hath not been often traduced to be the agent of his own by-ends, under pretext of reformation? So much the more I shall not be unjust to hope, that however infamy or envy may work in other men to do her fretful will against this discourse, yet that the experience of your own uprightness misinterpreted will put ye in mind to give it free audience and generous construction. What though the brood of Belial, the draff of men, to whom no liberty is pleasing, but unbridled and vagabond lust without pale or partition, will laugh broad perhaps, to see so great a strength of scripture mustering up in favour, as they suppose, of their debaucheries; they will know better when they shall hence learn, that honest liberty is the greatest foe to dishonest licence. And what though others, out of a waterish and queasy conscience, because ever crazy and never yet sound, will rail and fancy to themselves that injury and licence is the best of this book? Did not the distemper of their own stomachs affect them with a dizzy megrim, they would soon tie up their tongues and discern themselves like that Assyrian blasphemer, all this while reproaching not man, but the Almighty, the Holy One of Israel, whom they do not deny to have belawgiven his own sacred people with this very allowance, which they now call injury and licence, and dare cry shame on, and will do yet a while, till they get a little cordial sobriety to settle their qualming zeal. But this question concerns not us perhaps: indeed man’s disposition, though prone to search after vain curiosities, yet when points of difficulty are to be discussed, appertaining to the removal of unreasonable wrong and burden from the perplexed life of our brother, it is incredible how cold, how dull, and far from all fellow-feeling we are, without the spur of self-concernment. Yet if the wisdom, the justice, the purity of God be to be cleared from foulest imputations, which are not yet avoided; if charity be not to be degraded and trodden down under a civil ordinance; if matrimony be not to be advanced like that exalted perdition written of to the Thessalonians, “above all that is called God,” or goodness, nay, against them both; then I dare affirm, there will be found in the contents of this book that which may concern us all. You it concerns chiefly, worthies in parliament! on whom, as on our deliverers, all our grievances and cares, by the merit of your eminence and fortitude, are devolved. Me it concerns next, having with much labour and faithful diligence first found out, or at least with a fearless and communicative candour first published, to the manifest good of Christendom, that which, calling to witness everything mortal and immortal, I believe unfeignedly to be true. Let not other men think their conscience bound to search continually after truth, to pray for enlightening from above, to publish what they think they have so obtained, and debar me from conceiving myself tied by the same duties. Ye have now, doubtless, by the favour and appointment of God, ye have now in your hands a great and populous nation to reform; from what corruption, what blindness in religion, ye know well; in what a degenerate and fallen spirit from the apprehension of native liberty, and true manliness, I am sure ye find; with what unbounded licence rushing to whoredoms and adulteries, needs not long inquiry: insomuch that the fears, which men have of too strict a discipline, perhaps exceed the hopes that can be in others of ever introducing it with any great success. What if I should tell ye now of dispensations and indulgences, to give a little the reins, to let them play and nibble with the bait awhile; a people as hard of heart as that Egyptian colony that went to Canaan. This is the common doctrine that adulterous and injurious divorces were not connived only, but with eye open allowed of old for hardness of heart. But that opinion, I trust, by then this following argument hath been well read, will be left for one of the mysteries of an indulgent Antichrist to farm out incest by, and those his other tributary pollutions. What middle way can be taken then, may some interrupt, if we must neither turn to the right, nor to the left, and that the people hate to be reformed? Mark then, judges and lawgivers, and ye whose office it is to be our teachers, for I will utter now a doctrine, if ever any other, though neglected or not understood, yet of great and powerful importance to the governing of mankind. He who wisely would restrain the reasonable soul of man within due bounds, must first himself know perfectly, how far the territory and dominion extends of just and honest liberty. As little must he offer to bind that which God hath loosened, as to loosen that which he hath bound. The ignorance and mistake of this high point hath heaped up one huge half of all the misery that hath been since Adam. In the gospel we shall read a supercilious crew of masters, whose holiness, or rather whose evil eye, grieving that God should be so facile to man, was to set straiter limits to obedience than God hath set, to enslave the dignity of man, to put a garrison upon his neck of empty and over-dignified precepts: and we shall read our Saviour never more grieved and troubled than to meet with such a peevish madness among men against their own freedom. How can we expect him to be less offended with us, when much of the same folly shall be found yet remaining where it least ought, to the perishing of thousands? The greatest burden in the world is superstition, not only of ceremonies in the church, but of imaginary and scarecrow sins at home. What greater weakening, what more subtle stratagem against our Christian warfare, when besides the gross body of real transgressions to encounter, we shall be terrified by a vain and shadowy menacing of faults that are not? When things indifferent shall be set to overfront us under the banners of sin, what wonder if we be routed, and by this art of our adversary, fall into the subjection of worst and deadliest offences? The superstition of the papist is, “Touch not, taste not,” when God bids both; and ours is, “Part not, separate not,” when God and charity both permits and commands. “Let all your things be done with charity,” saith St. Paul; and his master saith, “She is the fulfilling of the law.” Yet now a civil, an indifferent, a sometime dissuaded law of marriage, must be forced upon us to fulfil, not only without charity but against her. No place in heaven or earth, except hell, where charity may not enter: yet marriage, the ordinance of our solace and contentment, the remedy of our loneliness, will not admit now either of charity or mercy, to come in and mediate, or pacify the fierceness of this gentle ordinance, the unremedied loneliness of this remedy. Advise ye well, supreme senate, if charity be thus excluded and expulsed, how ye will defend the untainted honour of your own actions and proceedings. He who marries, intends as little to conspire his own ruin, as he that swears allegiance: and as a whole people is in proportion to an ill government, so is one man to an ill marriage. If they, against any authority, covenant, or statute, may, by the sovereign edict of charity, save not only their lives but honest liberties from unworthy bondage, as well may he against any private covenant, which he never entered to his mischief, redeem himself from unsupportable disturbances to honest peace and just contentment. And much the rather, for that to resist the highest magistrate though tyrannising, God never gave us express allowance, only he gave us reason, charity, nature, and good example to bear us out; but in this economical misfortune thus to demean ourselves, besides the warrant of those four great directors, which doth as justly belong hither, we have an express law of God, and such a law, as whereof our Saviour with a solemn threat forbade the abrogating. For no effect of tyranny can sit more heavy on the commonwealth, than this household unhappiness on the family. And farewell all hope of true reformation in the state, while such an evil as this lies undiscerned or unregarded in the house: on the redress whereof depends not only the spiritful and orderly life of our grown men, but the willing and careful education of our children. Let this therefore be new examined, this tenure and freehold of mankind, this native and domestic charter given us by a greater lord than that Saxon king the Confessor. Let the statutes of God be turned over, be scanned anew, and considered not altogether by the narrow intellectuals of quotationists and common places, but (as was the ancient right of councils) by men of what liberal profession soever, of eminent spirit and breeding, joined with a diffuse and various knowledge of divine and human things; able to balance and define good and evil, right and wrong, throughout every state of life; able to show us the ways of the Lord straight and faithful as they are, not full of cranks and contradictions, and pitfalling dispenses, but with divine insight and benignity measured out to the proportion of each mind and spirit, each temper and disposition created so different each from other, and yet by the skill of wise conducting, all to become uniform in virtue. To expedite these knots were worthy a learned and memorable synod; while our enemies expect to see the expectation of the church tired out with dependencies and independencies, how they will compound and in what calends. Doubt not, worthy senators! to vindicate the sacred honour and judgment of Moses your predecessor, from the shallow commenting of scholastics and canonists. Doubt not after him to reach out your steady hands to the misinformed and wearied life of man; to restore this his lost heritage into the household state: wherewith be sure that peace and love, the best subsistence of a Christian family, will return home from whence they are now banished; places of prostitution will be less haunted, the neighbour’s bed less attempted, the yoke of prudent and manly discipline will be generally submitted to; sober and well-ordered living will soon spring up in the commonwealth. Ye have an author great beyond exception, Moses; and one yet greater, he who hedged in from abolishing every smallest jot and tittle of precious equity contained in that law, with a more accurate and lasting Masoreth, than either the synagogue of Ezra or the Galilæan school at Tiberias hath left us. Whatever else ye can enact, will scarce concern a third part of the British name: but the benefit and good of this your magnanimous example will easily spread far beyond the banks of Tweed and the Norman isles. It would not be the first or second time, since our ancient druids, by whom this island was the cathedral of philosophy to France, left off their pagan rights, that England hath had this honour vouchsafed from heaven, to give out reformation to the world. Who was it but our English Constantine that baptised the Roman empire? Who but the Northumbrian Willibrode, and Winifride of Devon, with their followers, were the first apostles of Germany? Who but Alcuin and Wickliff, our countrymen, opened the eyes of Europe, the one in arts, the other in religion? Let not England forget her precedence of teaching nations how to live.

Know, worthies! and exercise the privilege of your honoured country. A greater title I here bring ye than is either in the power or in the policy of Rome to give her monarchs; this glorious act will style ye the defenders of charity. Nor is this yet the highest inscription that will adorn so religious and so holy a defence as this; behold here the pure and sacred law of God, and his yet purer and more sacred name, offering themselves to you, first of all, Christian reformers, to be acquitted from the long-suffered ungodly attribute of patronising adultery. Defer not to wipe off instantly these imputative blurs and stains cast by rude fancies upon the throne and beauty itself of inviolable holiness: lest some other people more devout and wise than we bereave us this offered immortal glory, our wonted prerogative, of being the first asserters in every great vindication. For me, as far as my part leads me, I have already my greatest gain, assurance and inward satisfaction to have done in this nothing unworthy of an honest life, and studies well employed. With what event, among the wise and right understanding handful of men, I am secure. But how among the drove of custom and prejudice this will be relished by such whose capacity, since their youth run ahead into the easy creek of a system or a medulla, sails there at will under the blown physiognomy of their unlaboured rudiments; for them, what their taste will be, I have also surety sufficient, from the entire league that hath ever been between formal ignorance and grave obstinacy. Yet when I remember the little that our Saviour could prevail about this doctrine of charity against the crabbed textuists of his time, I make no wonder, but rest confident, that whoso prefers either matrimony or other ordinance before the good of man and the plain exigence of charity, let him profess papist, or protestant, or what he will, he is no better than a pharisee, and understands not the gospel: whom as a misinterpreter of Christ I openly protest against; and provoke him to the trial of this truth before all the world: and let him bethink him withal how he will sodder up the shifting flaws of his ungirt permissions, his venial and unvenial dispenses, wherewith the law of God pardoning and unpardoning hath been shamefully branded for want of heed in glossing, to have eluded and baffled out all faith and chastity from the marriage-bed of that holy seed, with politic and judicial adulteries. I seek not to seduce the simple and illiterate; my errand is to find out the choicest and the learnedest, who have this high gift of wisdom to answer solidly, or to be convinced. I crave it from the piety, the learning, and the prudence which is housed in this place. It might perhaps more fitly have been written in another tongue: and I had done so, but that the esteem I have of my country’s judgment, and the love I bear to my native language to serve it first with what I endeavour, make me speak it thus, ere I assay the verdict of outlandish readers. And perhaps also here I might have ended nameless, but that the address of these lines chiefly to the parliament of England might have seemed ingrateful not to acknowledge by whose religious care, unwearied watchfulness, courageous and heroic resolutions, I enjoy the peace and studious leisure to remain.

The Honourer and Attendant of their noble Worth and Virtues,

JOHN MILTON.

BOOK I

THE PREFACE

That Man is the Occasion of his own Miseries in most of those Evils which he imputes to God’s inflicting...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Areopagitica

- Of Education

- The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce

- Meditations upon Divine Justice and the Death of King Charles the First

- Autobiographical Extracts