![]()

CHAPTER 1

Digital Business Strategy

As was discussed in the Introduction, the world around us is changing at a rapid rate. We can see that more and more technological advancements are encroaching on roles we’ve historically considered to be ones that could only ever be filled by humans and we understand that the pace of this change is increasing.

Where previously the local superstore employed 30 cashiers to operate 30 cash registers, they now employ a couple of assistants to aid customers with using automated checkout technology. Even in coffee shops, automation is beginning to take over. Despite our ideas about how much we like that friendly barista, preliminary tests by Briggo Coffee—a fully automated coffee bar in Austin, Texas, where you can create your order precisely how you like it and save it for future orders—have shown that people get used to the bot-made coffee quickly and apparently enjoy it no less.

Artificial intelligence is even encroaching on creative jobs such as journalism, law, and accountancy, which were once thought safe from automation.

If companies are to succeed in today’s digitized environment, the digital aspects of business can no longer be distinct from the business as a whole, and the strategy of digital business can no longer exist in isolation of broader business strategy. The actions of digital businesses still belong to the tactical marketers and technologists, but the strategy of digital business belongs in the boardroom, where the C Suite [i.e., the CEOs, CMOs, CIOs, Chief Finance Officer (CFOs), and Chief Technology Officer (CTOs)] can come together and form a cohesive market-led digital business strategy. This digital business strategy—and the leadership that drives it—is the essential element for success.

The distinguishing characteristics that indicate the onset of disruption are when a current function of a business becomes more affordable, more effective, and more convenient than the current method. Where once a bank would charge its customers for setting up a direct debit, a third party can now handle the transaction by way of a mobile app at a fraction of the cost. While the bank doesn’t see this alternative method of payment as a threat in the early days, the fact remains that this is a more affordable, effective and convenient solution for the customer than the bank offers. Because the smaller business markets this feature with greater focus, it has the power to erode the banks dominance in this domain.

Many smaller companies do not necessarily have better technology or processes than larger companies, but the technology and processes they have are more accessible to their customers and customers see more value in the technology-enabled process than in the traditional process. The dilemma, then, lies in how larger businesses can better engage with and understand their customers so that they can deal with these competitors nibbling away at their business. Quite often, these larger businesses are well established—they have a large customer base and large customer value. Clayton M. Christensen argues that making an inferior but more cost-effective product to sell to the customers downstream is the answer—but in today’s market this is not the only answer. Christensen argues that technology causes businesses to fall and fail, but as we’ve discussed, technology is not the full story—technology is only the visible end of the transformation spectrum. By the time technology comes to change how people do things, or causes disruption in an industry, there has already been a huge amount of market sensitivity, culture change, strategy development, innovation, and education within the business using it.

When threatened by these newer, smaller businesses, most businesses respond by pinpointing the technology as the root cause of the disruption they face and then seek to install technology that is similar to, or more advanced than, their competitors, but in order to change businesses in a competitive way, it must be realized that the technologies and processes are only the final piece of a larger puzzle; they are the servants drafted in to answer the questions posed by a broader strategic process. In taking a closer look at this strategy process, we can see that while digital business strategy in and of itself is not the full story, it is the starting block on the track to better, smarter, more competitive business.

Before considering how to utilize technology, we must first understand where it fits within the overall strategic landscape.

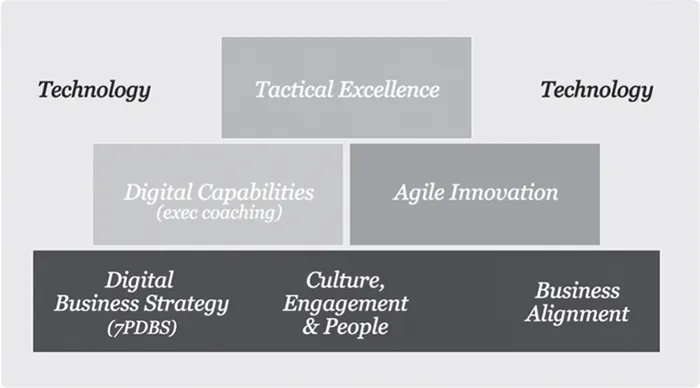

The Change Blocks of Digital Transformation

This model illustrates the high-level change blocks that should be addressed if an organization is to find new and sustaining competitive advantage in the digital world. In this sense, we say that these are the change blocks that must be considered if a business wishes to undergo “Digital Transformation.”

In terms of Digital Transformation, we understand the word “Digital” to be a synonym for the pace of change that’s occurring in today’s world, driven by the rapid adoption of technology. The word “Transformation” describes how an organization is built to change, innovate, and reinvent rather than simply enhance and support the traditional methods.

It shows that digital business strategy cannot be taken in isolation of culture. While this book deals almost exclusively with how to create a digital business strategy, an organization with the best strategy and poor culture is set for failure.

A rough but simple test of organizational culture is to check whether the management blocks access to streaming videos like YouTube or social media sites like Facebook, Twitter, or LinkedIn for their employees. Some managers claim that there are technical or security reasons why this should be so. The reality in most cases however is that the staff are not trusted enough by management to utilize these websites to further their knowledge and build better relationships. An organization with a positive digital culture seeks to provide training to its staff in gaining greater knowledge from YouTube, LinkedIn, and other social platforms rather than discourage their use.

The bedrock of the model is the interdependency between strategy, culture, communications, innovation, technology, and data in the emerging digital context.

Allied to this and representing the next level of enablement is the organization having the necessary competencies and behaviors that allow the business to become agile and innovative. An underlying competency in this dynamic space is the ability to recognize the change process as it is happening and of having the wherewithal to respond in an agile way.

Marketing Professor George Day, from Wharton University in Philadelphia, explained that staff increasingly need what he calls “adaptive” capabilities in facing this digitized economic context. By their nature, these new capabilities are anticipatory and more effectively compensate for the inherent ambiguity and uncertainty in advancing digitized contexts. The open and outward looking nature of these capabilities results in the organization being more innovative and agile in how it anticipates and responds to change and opportunity. Indeed, the increasing attention being paid to design school thinking as applied to business today has much of its roots in the ambiguity and uncertainty managers have been facing in increasingly digitized environments. Thinking more broadly and embracing and leveraging transdisciplinary approaches have been seen to add value to the speed and nature of responses to this level of change. Look at Philadelphia University’s new Strategic Design MBA not only as an example of disruption to the traditional and established MBA model but also as an entrepreneurial response to increasing uncertainty in the market and a desire in managers for the development of a different type.1

Indeed, a consequence of embracing an approach infused with digital business strategy will naturally expose gaps in education within an organization and identify where capabilities need to be enhanced. One of the key foci in creating a digital business is agile innovation. In her book, The End of Competitive Advantage, Rita McGrath, the Columbia business school professor, points out that the challenge of innovation comes from the fact that innovation itself is constant and gaining pace. Businesses that wish to create a strategy that relies on innovation then must change their culture to ensure the constant flow of innovation through the respective organization. She says that one of the most fundamental and recognized notions of business strategy—sustainable competitive advantage—can no longer be a holy grail for companies. Strategy must be combined with the right culture and deliberate cycles of innovation to succeed. While we all understand that the marketing environment is constantly changing (remember PESTEL, the tool for identifying threats and weaknesses used in a SWOT analysis), the speed and magnitude of such change, and the impact on lead times, now make it virtually impossible to respond in a way that allows for sustainable advantage. Deeply ingrained structures and systems designed to extract value, rather than being a competitive advantage, are becoming a liability.

When we look at digital business strategy, and indeed business strategy in general, we must take this into account. We must figure out a way in which to embed natural and constant innovation within our businesses and then go on to ensure that we have the tactical excellence to correctly execute the strategies fuelled by innovation.

Digital business strategy manifests itself by the way of technology-enabled education and data collection married with cycles of focused innovation, which are manifested using technology. Technology is the enabler, not the differentiator. Technology is not the agent of change, but the expression of the leadership thinking and strategy that goes before it. If we successfully execute these ideas with tactical excellence, we can create industry disruption, which leads again to further cycles of transformation through innovation.

Where strategy is market-led, it falls to the business to align the culture, to ensure that the associated capabilities required of the people behind the change imperative are in place, that the business processes are agile and aligned to the strategy and digital environment, and that excellence should emerge in the deployment and implementation of that strategy.

So where do we start in formulating a digital business strategy, and how does it differ from business strategy?

To answer this question, I’ll use an example from the courses we run for many of leading thinkers and business leaders. At the beginning of the course on digital business strategy, we hand out paper and ask people to write down their definition of strategy. We then bring these definitions together and look through them. The exercise doesn’t last very long, since most people in business have a clear idea of what strategy is. Everyone gets it right in some shape or form. Here are some examples of the answers people have put forward:

1. Strategy is about giving direction.

2. Strategy is about finding the best path to accomplishing a task and achieving a specific goal.

3. Strategy is a plan used to overcome defined challenges where there is a desired outcome.

4. Strategy is about understanding the problem before you start.

None of these definitions can really be faulted. When the definitions are collected, we use them to come up with a single sentence to describe strategy, and it’s usually something along these lines:

Strategy is a plan of action to give direction to overcome defined, specific challenges, and in conditions of uncertainty to achieve specific outcomes.

One we have agreed upon a definition; we examine it to see how it fits into different parts of our business.

We’ll take junior marketers as an example and examine what sort of strategy they work with, if indeed it can be called strategy at all. Do marketers have a web strategy or a social media strategy? If strategy is a plan of action to achieve goals in conditions of uncertainty, what were the conditions of uncertainty? What were the goals of the web strategy? What were the outcomes? In the courses we run, the tension in the room builds as we consider these questions. When we attempt to look at the work of marketers in this way, what we see is not strategy, but tactics. They are plans similar to those of an architect—complex and intricate—but we don’t say that an architect is creating a strategy. We say that she has designed plans.

Vocabulary is important, and often words are used symbolically in business. When we incorrectly identify tactics as strategy, we usually do so to elevate the importance of the tactics we propose. The word strategy gives what we present a gravitas, but of course, this can have a negative impact on the effectiveness of what we want to achieve—or perhaps more accurately—what we think we want to achieve. It makes people in the organization believe that we’re being strategic, when we are in fact being tactical. Worse still, these tactics are not coordinated never mind not being set in any overarching framework. It’s not strategic marketing, because in these instances, no overriding plan resembling what we call strategy has been given to the wider business. These tactics are important and functional in themselves, but they are not strategic. People like to immerse themselves in tactics because they’re more easily and more quickly measured than strategic change and can address the current pressure on immediacy of results and Key Performance Indicators (KPI) achievement. The risk that arises is that such tactics may allow for a degree of efficiency in how we are doing business but undermine our effectiveness in actually what business we are doing. In short, efficient tactics involves “doing things right”; effective strategy is about “doing the right things”.

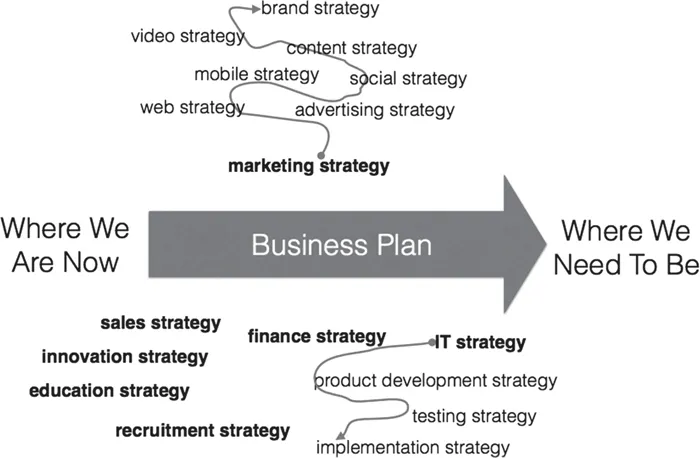

Many organizations have a business plan that lays out where they are now, where they need to be, and what way(s) they might get there. In most cases, this business plan is strategic—it explains the direction of travel, predicts and defines the challenges ahead, and calculates the resources that need to be committed. We then surround this business plan with sales strategy, innovation strategy, financial strategy, information technology (IT) strategy, education strategy, recruitment strategy, and marketing strategy.

If we start to examine these strategies, the picture becomes quite complex. To take marketing strategy as an example, when we drill down a little, we realize that things like web strategy, advertising strategy, brand strategy, mobile strategy, social strategy, video strategy, and content strategy are all included under this umbrella, and all these substrategies are only loosely woven together. The IT umbrella includes such things as product development strategy, testing strategy, and implementation strategy. Each of these strategies seem essential for the business—but are they really strategies?

If we look at these “strategies” using the definition of strategy we discussed earlier in this chapter, we can see that they are not strategy—they more closely resemble the architect’s plans. These are tactics. All of these tactics and subtactics draw from and give to the business plan—and the business plan, when we look at it in this light, becomes the digital business strategy. Through ...