Chapter 1

KNOWING AND CONTROLLING

Early Archaeological Exploration in the Algerian Colony

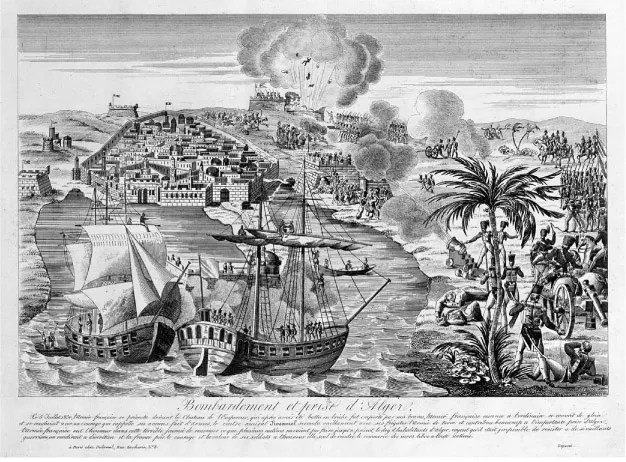

When French warships landed with thirty-seven thousand men at Sidi Ferruch, a port 30 kilometers west of Algiers in July 1830, they found the forces of the reigning Ottoman Dey Hussein ill prepared for their arrival.1 By this time, Algiers had grown from a modest town of roughly twenty thousand to a capital city of approximately a hundred thousand residents. In addition to a lucrative port, the city boasted a population that included as many as ten thousand janissaries.2

Following the debilitating three-year naval blockade of the city, local notables in the Regency of al-Jazā’er were dismayed by the inaction of local Ottoman leaders, who were divided by intrigue and too poorly equipped to wage an effective defense of the territory against the French landing. During the crisis, which followed fierce fighting, they counseled Dey Hussein to pursue a peaceful surrender of the city to French forces under the command of General Louis-Auguste-Victor Bourmont. Local elites such as Hamdan Khodja—a Kouloughli landowner (an ethnic group of mixed Turkish-Arabic heritage), law professor, and counselor to the Ottoman governor—argued that the city’s residents would fare better under such circumstances than if they waged armed resistance to the French forces.3 Hamdan, who read and spoke French and English in addition to Arabic and Ottoman Turkish, had high expectations of the French and their professed Enlightenment principles. As he recalled in Le Miroir (1833), although he and his contemporaries had no particular complaint against their Ottoman overlords, the severity of naval bombardment of Algiers made conditions desperate enough for them to submit to the French over-lords without a fight. In accepting the terms of the surrender of the territory, Bourmont granted the Ottoman dey assurances that inhabitants’ freedom of religion and property rights would be respected. According to Hamdan, the residents of Algiers had little reason to doubt that the French would honor the terms of the peace treaty.4

Figure 6. The bombardment and seizure of Algiers in July 1830. Reproduced by permission of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des estampes et de la photographie.

Despite Bourmont’s pledge to protect the civilian population and respect basic property rights, the armée d’Afrique began almost immediately to violate the provisions of the treaty. French soldiers sacked the Kasbah (citadel), confiscated land, destroyed homes, and plundered the civilian residences now occupied by officers and troops.5 The destruction of the city center in 1831 and 1832 was directed at creating an open space that could accommodate the armée d’Afrique and convey the imposition of French control.6 France believed that it had title to all of the former dey’s wealth, including public buildings and forts, palaces, the regency treasury, and the million or so hectares of agricultural land that comprised the Ottoman territory under his authority. French military officials also seized habous lands (A. waqf; Ottoman Turkish [T.]: vakif) in Algiers, namely the enormous wealth accumulated in the form of inalienable tax-exempt property that supported religious, charitable, and pedagogical foundations in the region as well as the poor in Mecca and Medina.7 Unabated land grabs by the French throughout the early decades of the occupation exacted a devastating toll on local residents.8

With the fall of the Bourbon king Charles X from power just three weeks after the invasion, there was initial hope in some quarters of Algiers that Louis-Philippe’s policies would be more moderate than those of his predecessor. But despite the use of the semaphore telegraph to speed communications between Toulon and the invading force, the new king had difficulty establishing direct control of military operations in Algiers. Bourmont was dismissed for refusing to recognize Louis-Philippe. In the general absence of guidance from officials in metropolitan France, many of whom were opposed to military intervention in North Africa, senior commanders of the armée d’Afrique began implementing policies of their own formulation.9 Some allowed serious matters to devolve to even their most junior subordinate officers. In the first years of the conquest, most French military officers had little sense of the strategic goals of the campaign beyond the poorly defined objective of liberating the Ottoman territory from alleged Oriental despotism.10 Once in the territory of al-Jazā’er, military commanders pressed strategies that would allow them to expand the territory under their control.

Although Algiers and its surrounding territories were not as unknown to the French as some writers later proclaimed, French officers faced many obstacles to establishing mastery over France’s newest possession.11 Because the French army evicted and exiled the Ottoman administration before learning anything about the existing systems of taxation, landholding, or justice, the arrival of French forces brought about the almost immediate cessation of all governmental institutions and activities. Unable to communicate in Arabic, not to mention in Berber, most French officers had great difficulty conducting even basic interactions with the Indigenous inhabitants. The consequences of this approach were especially severe given the elimination of the Hanafite Islamic tribunal (established by the Ottomans to hear sharia cases) on October 22, 1830, at the command of Bourmont’s successor, General Bertrand Clauzel.12 This deficiency caused frequent misunderstandings of local custom and religion. Officers in the cabinet of the duc de Rovigo, commander in chief of French troops in the former Regency of al-Jazā’er from 1831, had neither the resources for nor any apparent interest in a nuanced reading of the situation on the ground in Arab and Kabyle communities. In 1832, the duc de Rovigo was responsible for the seizure and conversion of Algiers’s primary house of worship, the Ketchaoua Mosque, which by 1845 had been transformed into the Cathedral of Saint-Philippe.13 In this institutional vacuum, the few Arabic translators available gained significant latitude in decision making on the ground.

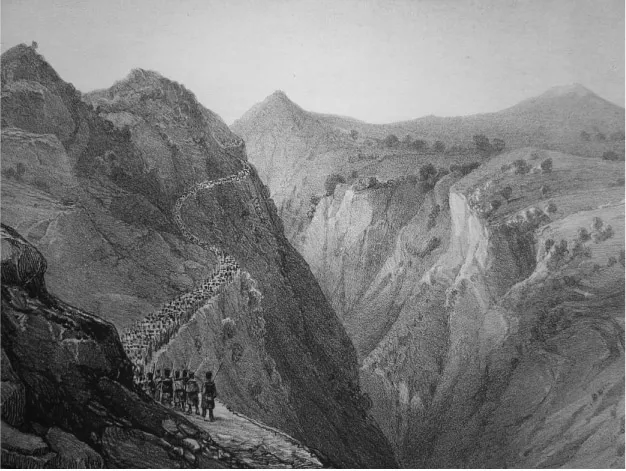

Figure 7. The traverse of the Atlas pass of Téniah (F. Col de Téniah) by the armée d’Afrique, commanded by General Bertrand Clauzel in November 1830, following its defeat of the Bey of Tittery’s force of eight thousand troops. Claude-Antoine Rozet, Voyage dans la Régence d’Alger ou Description du pays occupé par l’armée française en Afrique (Paris: Arthus Bertrand, Libraire-Éditeur, 1833), Atlas.

Symptomatic of Europeans’ fuzzy understanding of the Barbary Coast was the conflation of the history of the corsairs with the entire population of the region, despite the fact that the successful capture of booty had declined in the region for as much as a century.14 As observed by Perceval Barton Lord, a surgeon in the East India Company: “Tyranny and oppression are the features of a piratical government; it encourages those who follow a wild and reckless course, hazarding their lives in the cause of murder and rapine on the ocean; but for the arts of peace, the simple pursuits of the shepherd or the husbandman, it has no sympathy.”15

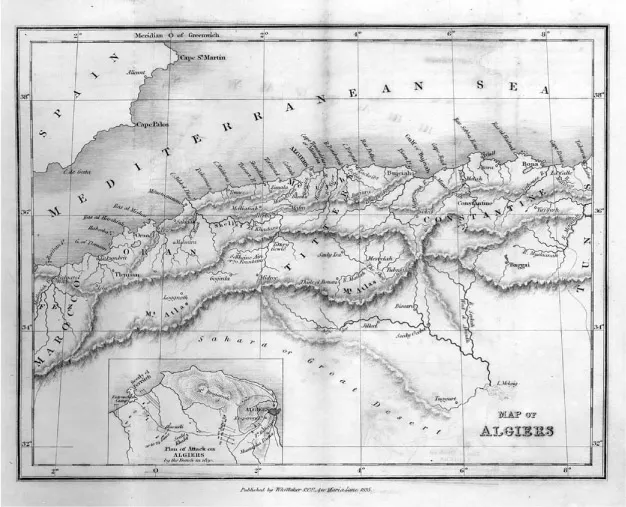

Figure 8. English map of the territory of Algiers and the surrounding region in 1835, much of which was not yet controlled by the armée d’Afrique. Perceval Barton Lord, Algiers, with Notices of the Neighbouring States of Barbary, vol. 1 (London: Whittaker, 1835).

Such scathing stereotypes of the population of Algiers and French memoirs of captivity in North Africa written at the turn of the nineteenth century helped render an already toxic situation even worse. Many troops feared for their lives should they fall into the hands of enemy combatants and overreacted to provocation with deadly consequences.16 In these early years, French forces were involved in several retributive massacres against the Arab population. These included most notoriously the indiscriminate killing of men, women, and children in the city of Blida, 35 kilometers southwest of Algiers, in November 1830, and nearly all of the El-Ouffia tribe in April 1832.17 Deficiencies in French leadership and the injustice of their actions quickly turned any initial good will or indifference among the Indigenous residents toward the invaders into rising resentment against their prolonged presence in the former Ottoman regency.

In the months and years after the conquest, the French recorded their impressions of the landscape of their new colony.18 At the same time, they rapidly transformed cosmopolitan centers such as the city of Algiers to meet European expectations of life in the occupied North African territory.19 These years saw the flight of large numbers of urban-dwelling Indigenous residents, whom the French typically identified by the centuries-old nomenclature of “Maures,” descended from a mix of Arabs and more ancient populations. Consequently, the demographics of coastal enclaves changed quickly and dramatically to include French troops and European civilians.20 The French presence in Algiers during the early years of the war brought an influx of not just soldiers and administrators but also civilian immigrants from Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, Malta, Spain, and the Balearic and Greek Islands, who sought livelihoods in the new colony.21 Seizing public and private buildings at will, the French also radically transformed the topography of Algiers in the 1830s and subsequent decades to accommodate French troops, European urban conventions, and larger numbers of wheeled vehicles.22 Beyond converting the Ketchaoua Mosque of Algiers into the Cathedral of Saint-Philippe and appropriating additional mosques for hospitals and structures meant to serve the army, the French embarked on building campaigns, both official and ad hoc.23

Although some blamed the chaos of this period on civilian settlers determined to thwart French military authority,24 both the army and European colonists were to blame for the violence against Muslim inhabitants and the irreversible damage to existing homes, religious establishments, and former government structures.25 As residents fled the violence, there was rampant speculation in property as French and European buyers sought to acquire urban and rural land. Some local landholders were threatened with expropriation of their possessions if they did not sell.26 Early among the victims of indiscriminate destruction by the French were several bazaars in which artisans produced and dyed silk fabrics, manufactured bracelets of African buffalo horn, and worked iron. Their elimination, along with land transfers in and outside the city that threatened the food supply, leveled a severe economic blow against the residents of Algiers, whose livelihoods derived from these local industries.27 The activities, many of which predated Baron Haussmann’s transformation of Paris under Napoleon III, rent the fabric of the city to accommodate European-style structures and open spaces for the future colonial capital.28

Similar to the manner in which they had viewed Egyptian Arabs, but with more devastating consequences because their stay in the Maghreb was more permanent, the French regarded the Indigenous residents primarily as an impediment to French ambitions.29 This blind spot, which has been described as a “space of noncivilization” by Abdelmajid Hannoum, exempted the French from seriously including Arab and Kabyle inhabitants in any colonial undertakings.30 These silences imposed on contemporary events allowed them to be recast in a manner consistent with the French mission of conquest.31 In the process of solidifying the colony, French administrators first busied themselves with identifying and appropriating the territory’s urban resources. Then, once they had established relatively secure bases, they began to study the territory with an eye to taking advantage of its agricultural resources. Discussion continued throughout the decade as to how the occupation of the territory of Algeria should proceed. Despite the enormous military cost of the venture, Louis-Philippe never seriously considered withdrawal due to the mark it would leave on France’s honor. In the early 1830s, policy discussions such as that held by the Commission d’Afrique on March 7, 1834, centered largely on whether the French presence should be restricted to a few coastal cities for defensive and commercial purposes or whether the conquered territory represented the seed for a larger civilian colony.32 The fact that thousands of French troops were already stationed in North Africa meant that the model of limited French presence and peaceful coexistence with Indigenous inhabitants never had a real opportunity to...