Introduction

For your birthday you get some extra cash and you decide to buy a new Bible. The local Christian bookstore should have what you want. As you enter the store and turn the corner into the Bible section, you immediately notice a plethora of choices. You see The Open Bible, The Thompson Chain-Reference Study Bible, The NIV Study Bible, The NRSV Access Bible, The Life Application Study Bible, The ESV Reformation Study Bible, The NKJV Women’s Study Bible, The KJV Promise Keepers Men’s Study Bible, The HCSB Study Bible, The Spirit-Filled Life Bible, and about fifty other possibilities. You didn’t know buying a new Bible could be so complicated. What should you do?

The first thing to know about selecting a Bible is that there is a big difference between the Bible version or translation and the format used by publishers to market the Bible. Packaging features such as study notes, introductory articles, and devotional insights are often helpful, but they are not part of the translation of the original text. When choosing a Bible, you will want to look past the marketing format to make sure you know which translation the Bible uses. In this chapter we will be talking about Bible translations rather than marketing features.

We have a chapter on Bible translations because translation itself is unavoidable. God has revealed himself and has asked his people to make that communication known to others. Unless everyone wants to learn Hebrew and Greek (the Bible’s original languages), we will need a translation. Translation is nothing more than transferring the message of one language into another language. We should not think of translation as a bad thing, since through translations we are able to hear what God has said. In other words, translations are necessary for people who speak a language other than Greek or Hebrew to understand what God is saying through his Word.

We begin our discussion of Bible translations by looking at how we got our English Bible in the first place. Then we will look back at the various ways the Bible has been translated into English from the fourteenth century to the present. Next we will turn our attention to evaluating the two main approaches to making a translation of God’s Word. Since students of the Bible often ask, “Which translation is best?” we will wrap up the chapter with a few guidelines for choosing a translation.

How Did We Get Our English Bible?

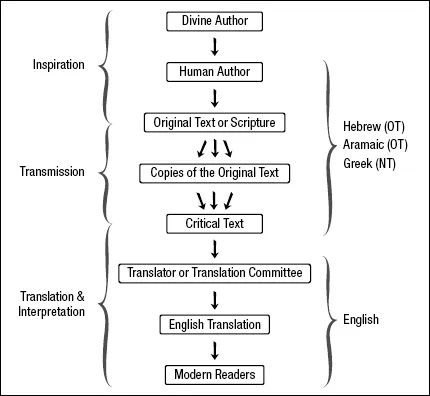

Kids ask the toughest theological questions. At supper one evening, right after hearing a Bible story on the Tower of Babel, Meagan Duvall (age five at the time) asked, “Who wrote the Bible?” What a great question! Meagan’s question is actually part of a larger question: “How did we get our English Bible?” or “Where did the English Bible come from?”1 Since the Bible was not originally written in English, it is important to understand the process God used to get the English Bible into our hands. Below is a chart illustrating the process of inspiration, transmission, translation, and interpretation.

We left you hanging regarding Scott’s answer to his daughter, Meagan. Using the language of a five-year-old, he tried to explain that God wrote the Bible and that he used many different people to do so. The Bible is entirely the Word of God (divine authorship), but it is at the same time the writings of human authors. John Stott clearly describes the divine-human authorship of the Bible:

Out of whose mouth did Scripture come, then? God’s or man’s? [Sounds a lot like Meagan’s question.] The only biblical answer is “both.” Indeed, God spoke through the human authors in such a way that his words were simultaneously their words, and their words were simultaneously his. This is the double authorship of the Bible. Scripture is equally the Word of God and the words of human beings. Better, it is the Word of God through the words of human beings.2

God worked through the various human authors, including their background, personality, cultural context, writing style, faith commitments, research, and so on, so that what they wrote was the inspired Word of God. As Paul said to Timothy, “All Scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness” (2 Tim. 3:16). God’s work through human authors resulted in an inspired original text.

As you might expect, in time people wanted to make copies of the original documents of Scripture (we refer to the originals as the autographs). Then copies were made of those first copies, and so on. As a result, although the autographs no longer exist, we do possess numerous copies of the books of the Bible. For example, there are over five thousand manuscripts (handwritten copies) of all or parts of the New Testament in existence today. Regarding the Old Testament, in 1947 Hebrew manuscripts of Old Testament books were discovered in the caves of Qumran near the Dead Sea. The Dead Sea Scrolls, as they are called, contain a portion of almost every book of the Old Testament. Prior to the discovery of the Scrolls, the oldest Old Testament manuscript dated to the ninth century AD. In other words, some of the copies found in 1947 were a thousand years older than anything previously known.

Before the invention of the printing press in the 1400s, all copies of the Bible were, of course, done by hand. As you know if you have ever tried to copy a lengthy piece of writing by hand, you make mistakes. The scribes who copied the copies of Scripture occasionally did the same. They might omit a letter or even a line of text, misspell a word, or reverse two letters. At times scribes might change a text deliberately to make it more understandable or even more theologically “correct.”

Consequently, the copies we have do not look exactly alike. Make no mistake, scribes were generally very careful, and you can rest assured that there is no textual dispute about the vast majority of the Bible.3 Nevertheless, there are differences in the copies, and we need some way of trying to determine which copy is more likely to reflect the original text. That responsibility falls to the discipline known as textual criticism.

Textual criticism (or analysis) is a technical discipline that compares the various copies of a biblical text in an effort to determine what was most likely the original text. The work of textual critics is foundational to the work of Bible translation, since the first concern of any translator should be whether they are translating the most plausible rendition of a biblical text. The work of the best textual critics is set forth in modern critical editions of the Bible. For the Old Testament the standard critical text is the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS). For the New Testament it is reflected in the latest edition of the United Bible S...