![]()

1

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF WEST AFRICAN DRUMMING AND DANCE IN NORTH AMERICA

From the Period of Slavery (1619–1863) until the Early 1960s

This book explores the strong presence of West African drumming and dance at North American universities, an ongoing process since 1964 that I describe as a resurrection. To offer a better understanding and appreciation of the reasons for calling West African drumming in the American academy a novelty, presence, and resurrection of a genre, it is crucial to situate this discussion by first evoking the broader a priori historical context that characterized the absence, disruption, and suppression of a symbolic musical tradition. Accordingly, I subsume this chapter under two historical phases: (1) Slavery (1619–1863), and (2) After Slavery until the Early 1960s. I will discuss drumming and dance in the North American academy from 1964 until the present day in subsequent chapters.

DRUMS, DRUMMING, AND DANCE DURING THE PERIOD OF SLAVERY

Although one cannot overlook the ethnic socio-cultural symbolic significance of specific African chordophones—Mande kora (Knight 1971, 1972; Charry 2000); the goje of the Fulbe, Dagbamba, and Hausa (DjeDje 2008); and tuned idiophones—Shona mbira (Tracey 1970; Berliner 1993), Chopi amadinda xylophones (Tracey 1948), Mande balo (Charry 2000), or Dagare gyile (Strumpf 1970; Mensah 1969), for example—I have observed elsewhere that “Drums are generally considered the most important musical instruments of Africans. … they are symbols of political power, … embodiment of black spirituality, galvanizing tools, uniting forces, speech surrogates, and exquisite artifacts” (Dor 2006: 356).1 For the sake of sound historicity, it is important to emphasize that enslaved Africans were not only taken from West Africa during the transatlantic slave trade, but also from different parts of Central and Southeastern Africa, as evidenced in Philip Curtin (1969) and more recent works including segments of essays in Holloway ([1990] 2004). And although my preceding observation regarding the importance of dance drumming applies to all the aforementioned regional sources of enslaved Africans, I want to redirect my focus on the geo-cultural scope of this book, West African drumming and North America. Given that West Africa has some of the most vibrant drumming traditions in the world, and as most transatlantic slaves came from this region, one would have expected a steady and undisrupted continuation in drum and drumming traditions in all parts of the African diaspora. Contrarily, drumming was suppressed during the period of slavery in what is now known as the United States of America (Southern [1971] 1997: 172; Roberts 1998: 22, 173). I explore this historical backdrop under 1) dislocation and partial disruption, 2) Christian liturgy as embedded and indirect disruption, and 3) slaveholders’ control as total suppression.

Socio-Cultural Dislocation as Partial and Natural Disruption of Drumming

Africa’s myriad socio-cultural institutions, structures, and systems inextricably inform the organization of its respective traditional music genres. Nketia (1963; 1974), Bebey ([1969] 1975), and several other African music scholars in their writings have adequately thematized this axiomatic and symbiotic interaction between music and social, political, and/or cultural phenomena (Stone 1982; Euba 1990; Ames 1971; Hood 1964; Agawu 1995; DjeDje 2007). Also generally resonant with the preceding are the theoretical perspectives of Giddens (1977) and Monson (2007), which support the dialectical interplay between music cultures and socio-cultural structures and systems.

However, upon the migration of Africans into the New World, with completely new landscapes, all musical practices of the slaves became uprooted from the original social-cultural institutions, structures, and systems that previously underpinned their existence back in homeland Africa. As a result, specific musical traditions died out. A classic example is the music associated with the royalty or courts in Africa, whether dance, praise poetry, or what Nketia (1963) calls “state drumming.” In addition to the nullification of socio-political structures is the centrality of the royalty—kings, chiefs, queen-mothers, or simply patrons, whose royal ancestry, political power and might, benevolence, and recompense the court musicians celebrated in praise poetry and regal dances. But in the light of the absence of the preceding rulers and the institution of chieftaincy in the diaspora, these court traditions that valorize rulers could not have survived. Thus, the replacement of the old African social terrains with new social formations and contexts in the New World engendered the natural extinction of certain drums and drumming traditions. I therefore suggest that the disruption of particular kinds of drumming in the African diaspora automatically and naturally started with this socio-cultural dislocation.

Yet, in critical discourse on the music culture of the African diaspora, specifically those that focus on African retentions, or the lack thereof, the contextual dislocation of musical practices from their African landscapes has not been given the attention it deserves. The circumscriptive and prescriptive authority of the slaveholder with reference to which musical types slaves were permitted or prohibited to perform is a common theme that authors often use in explicating the continuation or disruption of various domains of culture. Admittedly, the human factor and agency are central. However, I argue that the dislocation of dispersed Africans from their original homeland cultural, ecological, social, and political landscapes must be discussed along with how the people themselves were initially dislocated in their new lands. I think this geo-historical approach can complement the more habitual ways in which this topic has been approached.

Christian Liturgy as Indirect and Partial Disruption of Drumming Traditions

Religion is another important ambit under which the continuation or disruption of African drumming and dance in the diaspora can be understood. In homeland Africa, drumming and dancing are indispensable expressive and experiential domains of most traditional African religious practices, whether used as a means of invoking the presence of a divinity, inducing spirit possession in devotees, conditioning the momentary spirituality in an intermediary, a conduit of corporate expression of religious beliefs, or a vehicle for easy transition between different stages of worship, all which facilitates ritual efficacy (Rouget 1985; Nketia 1957, 1963; Friedson 1996, 2009; Kiehl 1999). Furthermore, Nketia (1968), Euba (2003), and Barber (2004, 2005) have discussed textual constructions in which a substantial amount of West African praise poetry is directed toward deities, whether sung or played on drums such as the Ghanaian atumpan or Yoruba dùndún. It is therefore legitimate to ask whether or not religious drumming traditions have been dislocated or discontinued like court drumming traditions and dances in the African diaspora. The answer to this question is the focus of the next few paragraphs.

The kind of intense indigenous praise singing, praise drum poetry, or dance that has survived among most identifiable groups within the African diaspora is that which lauds their objects of worship, within the context of continued practice of traditional African religions. Though transformed, drumming traditions within African-derived religious contexts in the diaspora have retained all the functions discussed in the preceding paragraph. Evidently, religious dances have preserved the traditions of drumming of which classic examples abound in Haiti, Cuba, Brazil, Jamaica, and also among the Sidi Indians, though with a different historical trajectory.

Contrarily, because most slaves in the United States converted to Christianity, they lost one of the major accesses to continued drumming and dancing during the time of slavery. Whether by intent or sheer coincidence, the volitional or coerced conversion of thousands of slaves in America to Christianity as their major religion can be viewed as an indirect, and perhaps unintended, perpetuation of the suppression of drumming in North America. At a time that African-derived religious practices of slaves in the Caribbean and Brazil, for example, remained a powerful medium through which religious dance drumming survived along with other Africanisms evidenced in cosmology and accompanying ritual behaviors, the Christian liturgy of some of these early Black converts in the USA, as Southern observes, was mainly European and without West African drumming.

Southern (1997: 178–179) has documented how the absence or extent of Africanisms in the black church before the Civil War (1861) depended on denominations of converted slaves, the degree of control or flexibility of white church leaders and slaveholders over the religious practices and expressions of slaves, and agency of black worshippers in the Southern colonies and later states. Not only did Eileen Southern stress the differences in attitudes of slaveholders in various colonies, but also those between the worship music of converted blacks in the urban and rural church. In European-African or black churches affiliated with Catholic, Methodist, Presbyterian, and Lutheran denominations, musical liturgy was desirably European, and for the sake of so-called authenticity, no room was allowed for Africanisms in regular worship services. “Negro worship music” was permitted for only a few special services. Given that the Protestant churches belonged to national conferences or societies, they ensured uniformity in liturgy. Writing on the beginnings of the religious folk songs of black Americans leading to the Spirituals, for example, Southern relates:

First, there were the black Methodists of Philadelphia adding choruses and refrains of “their own composing” to the standard Protestant hymns in Richard Allen’s hymnal of 1801. Then a few years later, in 1804, a visitor to Allen’s church ridiculed the “kind of songs” being sung at the church, implying that they were not orthodox hymns. Finally, in 1819 John Fanning Watson publicly aired the matter, protesting that the black members of the Society were singing their improvised hymns in public places and camp meetings. (Southern 1997: 180)

The preceding excerpt clearly articulates how uncompromising Protestant churches were regarding standardization of liturgy, perhaps aimed at enforcing church traditions including their related beliefs of efficacy in worship. It follows that such a landscape of regulated religious behavior was never a fertile site for even black Protestants’ use of drum substitutes, let alone West African religious dance drumming.

Black independent churches, mainly Baptist, whose congregations were led by black preachers were autonomous, therefore “free from regulations of a national body,” and rather controlled by local white church officers (Southern 1997: 178). Such a different and relatively more flexible atmosphere encouraged and enabled more black modes of worship and religious expression. No wonder the style of lining-out, especially of Isaac Watts hymns, has survived in black Baptist churches. But more notably related to this book’s theme is the practice of drum substitutes as evident in the ring shouts in which handclapping and foot stomping provide the rhythmic synergy and accompaniment to singing and dancing. As by African conception in which a symbiosis exists between drumming, singing, and dancing, ring shouts contain call-and-response singing, subtle dance movements that are differentiated from black secular dance behaviors, and polyrhythmic structures that worshippers produce on/from their bodies, as well as intermittent ululation ubiquitous to many African ethnic communities. A classic example of this intangible knowledge and endangered heritage of the ring shouts can be found among the Gullah living in McIntosh County on the Georgia Sea Islands. The Gullah-Geechee Ring Shouters are a group committed to becoming the living repository and perpetuators of their ancestors’ religious genre, though the Library of Congress has also documented performances of this genre by the Gullah group. Although the AME and AMEZ Churches also had black preachers, controlling national apparatuses made it hard for these churches to survive in the South.

Yet, as Southern observed, the majority of slaves were never permitted by slaveholders to convert to Christianity. However, the blacks of this category secretly formed the designated “invisible institution” or the “invisible church,” and strategized ways and means to worship in secret, even within their rigidly controlled circumstances. Though one may not rule out the possibility of these secret churches also resorting to drum substitutes including handclapping, foot stomping, and beating parts of the body during worship, the secrecy with which they conducted their gatherings, to the extent of masking and muting the preacher’s voice, leaves doubt with respect to any loud sonic outlets that might attract the attention and notice of slaveholders. Given that the intensity of the ring shouts or other singing and dancing might depend on where and when they worshipped, the main uncertainty that engulfs the religious practices of these secret churches is the secrecy itself. It is convincing for slaves to use songs with hidden transcripts such as “Steal away to Jesus” to cue themselves for times to converge for worship because, the use and evocation of such linguistic devices as situational knowledge expressions is a commonplace in black cultures. Also, the label of “secret institutions” superficially resonates with the closed religious societies such as the Sande and Poro of the Vai of Liberia (Monts 2000: 63–87), or the Yewe and Afa of the Ewe of West Africa. While future research may consider probing any possible Africanisms along such a geo-historical trajectory, it is abundantly clear that West African dance drumming might have been too loud for these secret groups and activities.

Contrarily, the eclecticism that characterized the religious practices of some blacks in Haiti, Cuba, and Brazil was more of a continuum than a revitalization of completely disrupted African-derived practices. In parts of the Caribbean and South America, the Catholic Church encouraged the continuation of some African cultural practices both within and outside worship. George Brandon discusses the formation and activities of Afro-Catholic fraternities in Cuba called cabildos, societies that were primarily ethnic-based that socialized and fellowshipped, among other things, through drumming and dancing outside of worship. These fraternities, according to Brandon, apparently enabled slaves of Yoruba descent to lay the firm foundations that nurtured the establishment of Santeria religion in Cuba, although not without the slaves’ own agency (Brandon 1998). Further, Tompkins (1998: 491) notes that during the period of slavery, the Catholic Church in Peru also encouraged slaves to engage in drumming as a way of socializing in brotherhood groups called cofrados. Such freedoms were absent in the church in North America during the period under review.

On the other hand, while slaveholders in North America might not have believed in traditional African religion, one can posit that they might have been aware of the almost boisterous ritual behaviors of possessed devotees of Voudoun, Candomble, or Santeria, and of the fact that some of the deities were/are war divinities with wrathful attributes. And since it is dance drumming that partly induces this spiritual transference from the physical to the metaphysical realm of experience in the devotee, it must be counted a blessing in disguise, from the perspective of the slaveholder, that most slaves in the United States became Christians. Yet the Christian faith partly constrained the continuation of African dance drumming in religious contexts.

Slave Holders’ Control as Total Suppression of African Drumming Traditions

Southern ([1971] 1997: 172), Roberts (1998: 22, 173), and several other scholars who have documented the outlawing of drumming during slavery, especially in the American South, all explain this suppression as a preventive strategy. Nketia not only discusses the diversity and symbolism of African drums, but also the three modes in which African drumming is done, namely, dance, signal, and speech (1963: 17). African drums’ use as speech surrogates to serve as sensitizing, mobilizing, and galvanizing tools for warriors to be psychologically tuned up for war is a commonplace that could not have eluded the knowledge of pragmatic slaveholders. And yet the reinforcement of slave labor from Africa in the eighteenth century, for example, was equally a reinforcement of the African cultural presence in the United States,2 not only in terms of the performing arts, but also of indigenous military knowledge necessary for resistance to subservience.

Writing on Africanisms in American Culture, Joseph Holloway mentions the Stono Rebellion of September 9, 1739, as a classic example of slaves’ resistance to subjugation, which included suppression of their ancestral heritage of drumming. On the other hand, the rebellion exemplifies a vindication for the rationale behind slaveholders’ suppression of drumming. This uprising took place in South Carolina when Jemmy, a slave believed to have come from Kongo or Angola, led other slaves in their agency for freedom. Compelling critical accounts on the Stono insurrection by Smith (2005: xiii), Shuler (2009: 3–4), and Kly (2006: 59) indicate that although the rebellion was relatively brief, the slaves’ symbolic use of drums and drumming as both a tool and object of liberation is noteworthy.

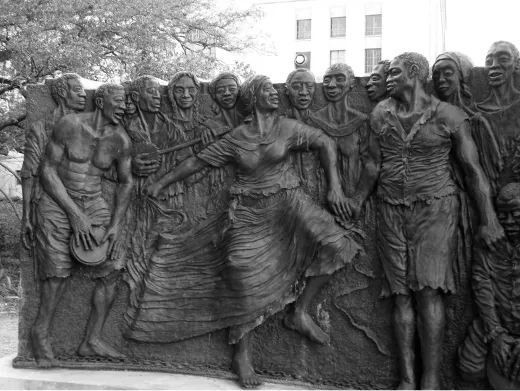

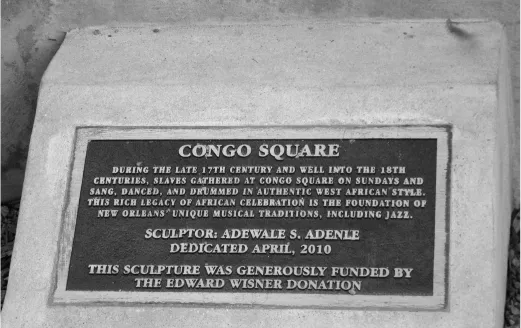

Consequentially, the aftermath of this rebellion was marked by the passing of what is known as the Negro Act of 1740 in which slave behavioral codes were tightened with tougher controls. Among other things, the act prohibited slaves from South Carolina from drumming, assembling in groups, or relocating to neighboring non-British colonies that granted slaves some degree of socio- cultural freedom, and gave legal cover to slaveholders to kill any slave who engaged in future rebellious acts. Also, the Negro Act of 1740 influenced the passing of the Georgia Slave Code of 1755, for another English colony. However, beyond broader generalizations, one needs to acknowledge the nuances and realities of the practices in autonomous southern states. Historians have observed that slaveholders in Spanish Florida granted much more socio-political freedom to their slaves than was the case in the English colonies. It is then easy to comprehend why the ban on slaves’ attempt to relocate to these neighboring states was part of the Negro Act of 1740. Furthermore, the cultural freedom of slaves in Louisiana in the eighteenth century deserves mention. At the same time that the Negro Act of 1740 prohibited slaves in South Carolina from assembling in groups, Southern writes on the practice of New Orleans slaveholders in the eighteenth century that they relieved their slaves from work on Sundays. This flexibility allowed them to gather at Congo Square, where they made music, danced, and generally interacted. While some may argue that such partial freedoms served as foundations of slave solidarity that later concretized and enabled the New Orleans slave rebellion in 1811 (after the French Revolution), the opportunity in any case allowed slaves the freedom at least to perpetuate their creolized culture, even though according to Southern, the drums that accompanied their dances were not African-derived.

Figure 1.1 Sculpture at Congo Square, Louis Armstrong Park, New Orleans. [Photo by George Dor, November 2012]

Figure 1.2 Label describing the above sculpture at Congo Square, New Orleans. [Photo by George Dor, Nove...