![]()

Chapter One: Suppose They Don’t Want Us Here?

Mental Mapping of Jim Crow New Orleans

And as I would be going to Dryades Street with my father . . . I would spell out words. And one word that I kept seeing was spelled c-o-l-o-r-e-d. And I was trying to sound out the word and I was saying col-o-red. What is col-o-red? And he told me, “That’s colored, and it means you.” And I was looking at the signs that were marked for my use that looked different from things that had “w-h-i-t-e.” And I always wanted to know why these things didn’t look as nice . . . so my father was trying to help me understand the kind of society in which I had to live. And he just told me that no matter what other labels placed on me, I determined what I was.

—Florence Borders interview, Behind the Veil oral history project (1994)

Growing up during segregation, Florence Borders discovered that she was “colored” in the space of urban New Orleans.1 As she traveled across the city and practiced her reading skills, she came to understand the meaning of race. The letters in the word “colored,” the sounds they made when strung together, and the quality of the things those letters marked taught her complex lessons about her place in Jim Crow society.2 Borders’s father simultaneously helped give meaning to the word “colored” as he attempted to teach his daughter to see herself as more than the narrow definition that hung from the signs she sounded out.

Geography and corresponding spatial relationships introduced Borders to the terms “colored” and “white.” She encountered the signs away from her home and neighborhood. As her recollection illustrates, girls learned what it meant to be “colored” in New Orleans and in the American South in both private and public spatial encounters. Everywhere they turned, they saw signs that marked them as outsiders, public benches they could not sit on, and dressing rooms where they could not try on clothes. This was the reality of racial segregation and part of the violence of the double bind.

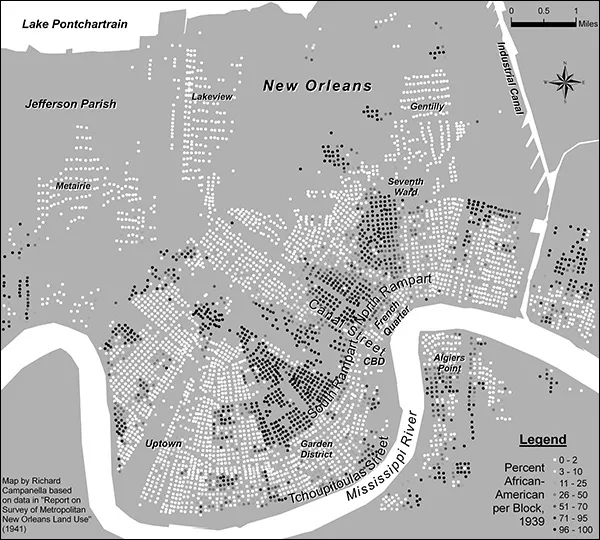

FIGURE 1.1. New Orleans’ population distribution by race, 1939 (map by Richard Campanella)

Mental Maps and the Politics of Place

“I am struck by the centrality of space—the rhetoric of spatiality—to the locations of identity within the mappings and remappings of ever changing cultural formations,” observes feminist scholar Susan Friedman.3 This “rhetoric of spatiality” was especially intense in segregated southern cities. The Jim Crow state effectively controlled space and employed spatial language—boundaries, borders, insides, and outsides—to create a biracial order. The biracial order flattened New Orleans’ racial and ethnic diversity by dividing the city into only “white” and “colored.”

The ideology that whites and blacks must always be completely separated emerged during the waning days of Reconstruction.4 For white supremacists in the city, spatial separation ensured racial dominance while spatial proximity became a metaphor for racial equality. In 1892 a white New Orleanian declared, “We of the South who know the fallacy and danger of race equality, who are opposed to placing the negro on any terms of equality, who have insisted on a separation of the races in church, hotel, car, saloon, and theater . . . are heartily opposed to any arrangement encouraging this equality, which gives negroes false ideas and dangerous beliefs.”5 Even figuratively, race relations between blacks and whites came to be understood spatially, as W. E. B. Du Bois elegantly framed it in 1903: “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line.”6 But children in New Orleans did not experience the segregated space around them in two dimensions. They did not encounter simple, flat lines; instead, the world around them was alive with the three-dimensionality of space, influenced by social encounters, emotions associated with places, and the physicality of bodies—big bodies, barely visible bodies, bodies marked by their color.

Black girls in New Orleans developed mental maps that helped them understand themselves and their racialized city. As architectural historian Rebecca Ginsburg describes, mental maps are “multi-layered” and “fragmented.” They are multiple, conceptual scales of the city and its buildings, streets, ecology, play areas, and people imperfectly meshed together.7 Children’s mental maps are not to scale, nor do they correspond neatly with cartographers’ mappings of the city. Instead, they reflect children’s own experiences, their cognitive development, and their growing sense of the world around them. During Jim Crow, mental maps provided “imaginative order” to black girls’ worlds and helped them form a growing “awareness of racialized space.”8 This awareness of race, geography, and place is clear in playwright and activist Endesha Holland’s remembrance of Jim Crow Mississippi: “Although I didn’t know it then,” she recalled, “the houses in Greenwood gave me my first lesson in race. I learned that color and money went together. I learned that houses had skins, just like people, and just like people they were segregated by color and money.”9

Just as Endesha Holland did in Greenwood, Mississippi, children in New Orleans placed themselves, their homes, and their bodies on mental maps, thus defining themselves and their place in the city. Herbert and Ruth Cappie, both teenagers in New Orleans during the 1930s and early 1940s, articulated the complex and ever-shifting notion of “place” they dealt with as they came of age during Jim Crow. Herbert Cappie noted, “The most difficult thing about segregation was in knowing one’s place. In New Orleans, my place may have been over here, and in Alabama it was in another place over there. You had to know how to deport yourself in different places.” Ruth Cappie added, for emphasis, “That’s like in foreign countries.”10 Segregation and race-making in one Jim Crow city was not exactly the same in the next. Further, different spaces within a single Jim Crow city might have vastly different rules for the proper “place” for black citizens. This made mental maps all the more important for black children. Indeed, white children did not have to conceptualize urban space in this way. For instance, white memoirists often remember exploring New Orleans’ streets with freedom and abandon and without fear.11 But, as the Cappies’ interview demonstrates, place in legally segregated cities was extremely complex for black children; one had to constantly learn and relearn the proper space for and deportment of “colored” citizens, or they might be arrested or harassed by city workers, officers, sheriffs, or white citizens more informally policing the streets. Figuring out one’s place was made more difficult by the fact that spaces and the meanings associated with them, though seemingly self-evident and stable, were never fixed.12

In New Orleans, black children moved about in a topography marked by color and thus had to figure out their “place” in every space they entered.13 Rather than simply noting the city’s population distribution, Figure 1.1 visually demonstrates the complexity of moving around a segregated city, of moving from black space to white space, to gray space and back again. As black children moved through segregated spaces—through white neighborhoods, black neighborhoods, and interracial neighborhoods—they learned about the relationship between color, gender, and power. As black bodies were in motion, so too were their senses of self.

Black children in New Orleans developed mental maps of the city reflecting the racial-sexual domination of space. For black girls, this influenced things as mundane and yet as significant as their movement through the city and their bodily comportment. In the autobiographical essay “Growing Out of Shadow,” Margaret Walker remembers coming to a realization of “what it means to be Black in America.” For her, shadows represented the space of Jim Crow—restricting childhood movement and growth. Walker’s essay begins by reflecting on childhood encounters, moments of learning about proper place. Walker, who lived in New Orleans as a girl, writes, “Before I was ten I knew what it was to stay off the sidewalk to let a white man pass; otherwise he might knock me off. I had had a sound thrashing by white boys while Negro men looked on helplessly.”14 Walker learned early how to walk the city streets deferentially. She learned where her body belonged in relationship to whites, whether they were men or boys. Walker’s encounter with white boys on segregated streets demonstrates the ways in which black girls’ mental maps had to represent racialized and gendered power in the city. Geography influenced black girls’ subjectivities, bodily comportment, and sense of place in New Orleans. Black girls sometimes walked the city streets carefully, figuring out where they belonged.

Mapping Black Girls’ Neighborhoods: Uptown and Downtown Children

In the pages of the nineteenth-century African Methodist Episcopal Church Review, tourist Willietta Johnson described a charming, scenic New Orleans. She explained that the city was “cut by Canal Street into two phases of life, two epochs of history, and two methods of thought.” French and Spanish culture survived in the slice of the city below Canal Street, which was full of Old World splendor, foreign chatter, and “beautiful women, convents, chapels, cemeteries and seminaries, all of which are tinged with an oriental charm.” “The upper portion of the city,” she wrote, housed the garden district and “the beautiful as well as the characteristic southern home, planted in lovely lawns.”15

Willietta Johnson visited New Orleans in 1893. Plessy v. Ferguson, the case that eventually enshrined “separate but equal,” was already winding its way through the court system. New Orleans railways had separate cars for different races, and the city was well on its way to Anglo-Americanization and eventually to solidifying legalized segregation. The ugly underbelly of the city was invisible to Willietta Johnson or, more likely, was not a part of the enthralling, exotic portrait she wished to create for her readers. Although her account was more flawlessly poetic than reality, one thing Johnson took note of was true—Canal Street demarcated the middle of the city, separating two ways of life.

New Orleanians reveal a particular geographical knowledge of the metropolis; their memories provide insight into the symbolic importance of the city’s streets. Oral history interviewees constantly referenced Canal Street and, like Johnson, represented it as a cultural crossroad. Interviewees described who they were and where they came from by beginning with “uptown” and “downtown.” One oral history interviewee, for example, responded to the question, “Where did you grow up?” with, “In the uptown section. As a matter of fact, I was born within about fifteen, twenty blocks from here, in the uptown section of New Orleans.”16 Canal Street was the functional dividing line between the uptown and downtown sections of the city and between two socially distinct black communities.17 Even white New Orleanians felt this way. In the joint memoir Uptown/Downtown, two women who grew up in the city noticed that “in comparing notes about our growing up years we discovered that while we shared the same unique culture and customs of New Orleans, we often experienced them differently. One of us had an ‘uptown’ experience and the other had a ‘downtown’ experience.”18

This sense of place, of marking oneself as uptown or downtown, gave New Orleanians a way to describe who they were and deeply informed their subjectivity. But, according to civil rights activist Charlayne Hunter-Gault, the impulse to “place” oneself geographically is a feature of southern subjectivity more broadly. In her memoir In My Place, in which she recalls her coming-of-age as a black girl in the Jim Crow South, Hunter-Gault continually plays with the idea of “place” and its many meanings. Of placing oneself in one’s community and personal history, she says, “Ask any Southerner where he is from and he will tell you every place he has ever been from. I am no exception. I always say, ‘Well I grew up in Georgia, but I’m from South Carolina.’ ” Hunter-Gault argues that the multiple places and geographies she associated with gave her a “strong sense of place.”19 Similarly, in From the Mississippi Delta, Endesha Holland begins her life story with the specificity of place—she first describes Gee Pee, “the roachy heaben o’ de Delta,” a respectable black neighborhood in Greenwood, Mississippi.20

Because of the bifurcation of uptown and downtown in New Orleans, black youths’ mental maps began with their neighborhoods. But these maps began to expand once they ventured into new sections of the city or met youth from other parts of town. Children and adolescents often met at Catholic schools: some would travel uptown to go to Xavier Prep; others would travel downtown to go to St. Mary’s. Likewise, many teenagers came together because throughout the 1930s, the city had only one “colored” public high school, McDonogh #35 (an industrial high school, Booker T. Washington, opened in the early 1940s). Florence Borders, who graduated from McDonogh #35, explained the cultural divisions within black society: “Generally you were an uptowner or a downtowner, all across the board. And when we got to 35, we met people for the first time who were in our age group, and in our class, and from another section of the city. But there was always a consciousness of being an uptowner or a downtowner. . . . One of the girls who was in my class married a ‘downtown boy.’ ”21 Borders laughed and used vocal intonation to imply that a “downtown” boy was scary, different, and possibly even dangerous. She did so lightheartedly, but her narrative pointed to the fact that perceptions of the difference between the two sides of the city were extreme enough to remark on inter-neighborhood dating. Uptowner Millie McClellan Charles also spoke of McDonogh #35 as a cultural meeting ground between two separate communities. “I had never known the other high school kids that were below Canal Street until that happened, because I never traveled below Canal Street, except for with my grandmother who went to the French market every Saturday,” said Charles. When she arrived at the school, she “marveled at the fact that they had lifestyles that were different. They were predominantly Catholic. The Creole mentality was very strong there.”22 Charles’s reference to “lifestyles” and “mentalities” highlighted the dist...