![]()

1

What’s the Matter

with Food?

ANYONE WALKING into my neighborhood Marketplace IGA food store would be hard pressed to know why people are angry, anxious, or even concerned about the food that’s available to most middle class North Americans.

Everything I could want is there: year-round organic bananas from Ecuador, fresh bread from local bakeries, so many dairy confections you need a nutrition degree to tell them apart, grains and nuts (in bulk or in packages), olives from Greece, local blueberries in season, spices from India, fair trade coffee from Nicaragua — there’s more food and more choice than the richest people in the world could have dreamt of only 200 years ago. The average supermarket in the United States has 47,000 products. My grocery store has no shortages, no empty shelves. It does have massive waste, however. I witness it when I’m there at closing time and see them dumping everything from the deli section.

When I load up my bag in Canada or the United States, I’m paying the lowest percentage of my income for food than citizens in any other country in the world do. And I could be paying even less if I walked two blocks to the No Frills store, where the lighting is more austere and the “best before” dates are sooner.

In the United States, a food shopper gets to choose from an average of 50,000 different food products on a typical supermarket outing. The American food system makes an average of 3,800 calories a day available to every person, more than one and a half times their average daily need. The invisible hand of the free market appears to be doing its job: nothing is rationed, and everything I see around me is being delivered efficiently and abundantly because of intense market competition for my food dollar. So why exactly are so many people engaged in a “food revolution”? Do we really need to intervene in the efficient, cheap flow of food provided by the free market?

Fewer Suppliers, Greater Risks

The answers are hidden in that store, mostly out of sight — and deliberately out of mind. The flaws in our food system start with the relatively few companies that control what’s being sold. The invisible hand of the market is not concerned with how many suppliers there are, but it does demand that they focus on their own prosperity, not our dietary well-being, or farmers’ incomes, or environmental pollution. Yet our lives, literally, depend on these few companies’ industrial supply chains. “Never in the field of human consumption has so much been fed to so many by so few,” notes British architect and historian Carolyn Steel.1

For example, five companies control 90% of the global grain market. In the United States, almost all the meat supply is controlled by four companies: Tyson, Cargill, Smithfield and JBS in Brazil. Cargill and two other companies process more than 70% of US soybeans, which are used to feed livestock and make much of the processed food we find in the grocery store.

Corn is a staple in livestock feed and is present in virtually all processed food and in an estimated 25% of all foods in a typical supermarket. Monsanto’s genetically engineered corn covers 85% of total US corn acreage.

While corporate concentration doesn’t necessarily mean that supplies are threatened, it guarantees that what food is supplied — and how those foods are grown and prepared — is in the hands of a few people completely outside our control, and mostly outside our regions. And the difference between food and those other two essential elements of survival — clothing and shelter — is that if someone stopped making our shelter and clothing for us, we would have time to regroup and adapt. With food, supply breakdowns have immediate and devastating impacts.

The same concentration and lack of diversity can be seen in the types of food we eat. The limited varieties of flora and fauna that meet the needs of a globalized food system are wiping more diversified products off the supermarket shelves and destroying the resilience that comes with biodiversity. This too adds vulnerability. Ninety percent of North American milk comes from the same breed of cattle; 90% of our eggs come from the same breed of hen.

The ‘Gros Michel’ banana is the type of banana our grandparents enjoyed. It was wiped out by Fusarium wilt (a.k.a., Panama disease). Because all commercial bananas are seedless, every banana is a clone, and thus equally susceptible to the same disease. “Billions of identical twins means that what makes one banana sick makes every banana sick,” notes Dan Koeppel, author of Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World.2 The banana industry was rescued by the introduction of the now-ubiquitous ‘Cavendish’ banana, but it is susceptible to the same fate as its predecessor.

When the same species is planted in vast plantations, they become an all-you-can-eat restaurant for pests. Once a pest figures out how to attack that one kind of plant, it’s open-season feasting on every plant in the field. As a response, we apply pesticides that contaminate the water, break down soil structure, deplete the soil’s fertility, and decimate the soil’s natural population of organisms.

To keep things growing, soil is replenished with loads of nitrogen, only a fraction of which is used by plants. The rest flows into rivers and waterways, feeding deadly algal blooms that suffocate aquatic life (most famously in the 6,000-square mile “dead zone” that flares each spring at the mouth of the Mississippi River). Much of the excess nitrogen is converted into nitrous oxide gas, which is accelerating climate change.

The vulnerability of any monoculture to disease and the concentration of production in fewer places compromises our food safety. In 2008, a Listeria outbreak at one meat plant in Toronto caused 22 deaths and hundreds of hospitalizations across Canada before all the tainted products could be identified and recalled. Typical carriers of food pathogens are no longer just the usual suspects — meat, poultry and eggs — now, leafy greens can be the culprit. In the summer of 2010, a new strain of E. coli bacteria was found in ready-to-eat salad mixes packaged at one big center, triggering a new wave of recalls. Prepared salads are vulnerable both to contamination from handling and from bacteria taken into the leaves when irrigation systems are contaminated, or when improperly treated manure compost is used as fertilizer. Unlike meats and eggs, there’s no cooking to kill pathogens.

Also invisible in my neighborhood grocery store are the antibiotics used to accelerate growth in cattle, poultry and hogs. These drugs are directly related to the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in humans.

Less Soil, More Meat, More Competition for Water

The way our food is grown also undermines the likelihood that it will remain healthy, cheap and plentiful. Soil is eroding off North American farmland at an alarming rate. The vast prairies — the famed North American breadbasket — have lost half their original topsoil. And erosion from agriculture continues to sweep away soils 30 times faster than new soil is being produced.

Around 2 million acres of cropland go out of production every year because of erosion, soil depletion or waterlogging. Another million acres a year are lost to development. Because food crops drain more nutrients than natural grasses, the soil that remains is increasingly dependent on fossil fuel-based fertilizers for nutrients.

Growing water shortages cannot help but hit agriculture hard. In Asia, 70% of all fresh water is used for growing rice. In a world where 2–5 million people already die every year from lack of potable water, the demand for fresh water will exceed supply by over 60% within a generation. Half of the world’s people live in countries where water tables in aquifers are falling because of overpumping. Saudi Arabia used to be self-sufficient in wheat, which was irrigated by a now-depleted fossil aquifer. From 2007–2011, Saudi wheat production dropped by two thirds. By 2012, it’s expected that Saudi Arabia will have to import all its wheat.

The Ogallala Aquifer, which sits in the middle of the United States, is the source of irrigation for 20% of America’s farmland. It is being overdrawn by 3.1 trillion gallons a year. As available water supplies shrink, the cost of foods requiring large amounts of water is bound to go up, as does the chance that those foods will become less available.

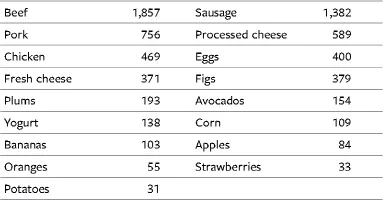

Table 1.1 Gallons of water required to produce one pound of food.

Source: National Geographic supplement, April 2010

Food shortages are already commonplace in many parts of the world. Globally, an estimated 963 million people — or about 15% of the world’s population — were undernourished in 2008. In March of that year, riots broke out from Haiti to Bangladesh to Egypt as people were hit with annual price increases of 130% for wheat, 87% for soy, 74% for rice, and 31% for corn.

Food shortages and price increases in 2009 sent another 75 million people into the ranks of the hungry. A drought in Russia in 2010 triggered a ban on wheat exports — part of a disturbing trend of food-producing nations protecting supplies for domestic needs. As the world’s population keeps growing and consuming resources faster than they can be replaced, future food shortages and price hikes are inevitable.

In 2010, the food price index hit record highs, and the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that food production will have to increase 70% by 2050 to feed a world population that’s headed to 9.1 billion people (from 6.8 billion in 2010).

Of the food that is produced, distribution is skewed to the point that there are as many obese people as there are starving people. Ironically, in Western societies obesity is closely related to low income, where people aren’t getting enough healthy food, resorting instead to sugar-and fat-laden fast foods — when they can find food at all.

Food shortages are exacerbated by the growing appetite for meat in countries like China and India. Grains that could go a lot further feeding people directly are being diverted to feeding animals for meat.

Although the United States rightfully prides itself as the breadbasket of the world, in 2006 — for the first time — the value of food imported into the United States exceeded the value of food exported from the United States. In 2009–2010, Australia had its first year as a net importer of food — and that was before the Queensland floods of 2010 that ruined thousands of acres of agricultural land.

The changes in imports and exports could be a reflection of the shrinking land base for agriculture, as agricultural lands around city edges get turned into housing lots and pavement. According the American Farmland Trust, more than 6 million acres of agricultural land in the United States were lost to development between 1992 and 1997 alone.

No Oil, No Food

Our food is “swimming in oil.” The food industry is dependent on oil for all its materials and at every stage of production: fertilizers, farm equipment, distribution to markets, refrigeration, getting it home from the store, etc. To be complacent about peak oil is to be complacent about ensuring our future supplies of food. A July 2010 report from the UK is one of the direst warnings to date. The Lloyd’s insurance market and the Royal Institute of International Affairs say Britain has to be ready for “peak oil” and disrupted energy supplies at a time of soaring fuel demand in China and India, constraints on production, and political moves to cut CO2 to halt global warming. They might also have mentioned competition with biofuel producers. Their report says companies and industries (they could have added “cities”) that fail to take advantage of the new energy reality could face “expensive and potentially catastrophic consequences.”3

Richard Ward, Lloyd’s CEO, says we’re in a period akin to a phony war. “We keep hearing of difficulties to come, but with oil, gas and coal still broadly accessible — and largely capable of being distributed where they are needed — the bad times have not yet hit.”4

One strategy for combating dependence on oil is to grow biofuels, but that collides with our need for those crops for food — another pressure point on our food supplies. In the United States in 2009, almost 30% of the grain harvested went to ethanol distilleries to produce fuel for cars. That’s enough food to feed 350 million people for a year.

Sadly, the oil that grows our food is also contributing to climate change. Floods such as those that devastated Pakistan and Australia in 2010, the Russian drought in the same year that decimated harvests, and rising sea levels are all reducing agricultural production. So are record high temperatures: crop ecologists estimate that for every 1 degree Celsius rise in temperature above optimum levels during the growing season, grain yields will decline by 10%. As of 2011, rising sea levels are threatening 20 major rice-growing river deltas in Asia.

Policies created to lessen the impact of climate change by reducing CO2 emissions are more bad news for affordable food. Twenty-five percent of greenhouse gas emissions in the world are from agriculture. One study found that 83% of total household emissions stemmed from the production of food. By one calculation, the production of meat is responsible for more greenhouse gas emissions than the entire transportation sector.

One way to reduce oil dependency is to eat more local food. A Canadian study on “food miles” estimated that sourcing 58 food items locally or regionally rather than globally could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by about 50,000 tons annually. That’s the equivalent of removing almost 17,000 vehicles from the road.

And what about all the fish on display at my local grocery store? That supply is shrinking too. According to the UN Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, “the demand for both freshwater and marine fish will expand because of increasing human population and changing food preferences, and the result will be an increasing risk of a major and long-lasting decline of regional marine fisheries.”5

All fish stocks are currently in decline, with some researchers predicting the collapse of all our seafood sources by the middle of this century. That doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll disappear or that we won’t do something to reverse those catastrophic trends. It almost certainly means fish will get more expensive and out of reach to a growing number of people. Fish farming, which still depends on feedstock from the oceans, won’t be able to fill the void.

No Farmers, No Food

Back on the farm, the financial squeeze on farmers is driving the next generation of farmers off the land, leaving aging farmers to provid...