eBook - ePub

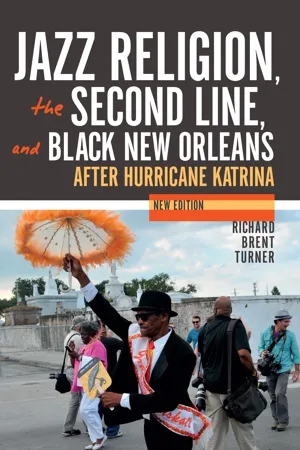

Jazz Religion, the Second Line, and Black New Orleans

After Hurricane Katrina

- 236 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This scholarly study demonstrates "that while post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans is changing, the vibrant traditions of jazz . . . must continue" (Journal of African American History).

An examination of the musical, religious, and political landscape of black New Orleans before and after Hurricane Katrina, this revised edition looks at how these factors play out in a new millennium of global apartheid. Richard Brent Turner explores the history and contemporary significance of second lines—the group of dancers who follow the first procession of church and club members, brass bands, and grand marshals in black New Orleans's jazz street parades.

Here music and religion interplay, and Turner's study reveals how these identities and traditions from Haiti and West and Central Africa are reinterpreted. He also describes how second line participants create their own social space and become proficient in the arts of political disguise, resistance, and performance.

An examination of the musical, religious, and political landscape of black New Orleans before and after Hurricane Katrina, this revised edition looks at how these factors play out in a new millennium of global apartheid. Richard Brent Turner explores the history and contemporary significance of second lines—the group of dancers who follow the first procession of church and club members, brass bands, and grand marshals in black New Orleans's jazz street parades.

Here music and religion interplay, and Turner's study reveals how these identities and traditions from Haiti and West and Central Africa are reinterpreted. He also describes how second line participants create their own social space and become proficient in the arts of political disguise, resistance, and performance.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Jazz Religion, the Second Line, and Black New Orleans by Richard Brent Turner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Jazz Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

The Haiti–New Orleans Vodou Connection: Zora Neale Hurston as Initiate Observer

The Negro has not been Christianized as extensively as is generally believed. The great masses are still standing before their pagan altars and calling old gods by new names.

ZORA NEALE HURSTON, THE SANCTIFIED CHURCH

The story of Zora Neale Hurston’s journey as an initiate observer of Vodou and her “introspection into the mystery” of the religion is an extraordinary religious narrative. Hurston interprets the key themes of Vodou, taps the magical-spiritual wisdom of her elders and ancestors, and records what Haitian adepts call konesans—the esoteric spiritual knowledge of ordinary black folk who create transformative healing rituals in the communities of the African diaspora. These ancestral, esoteric, and healing elements in Hurston’s spiritual journey are also the essence of the religious domain of second-line culture.

The chapter explores the religious significance of Hurston’s initiation and fieldwork in Vodou in the 1920s for the construction of a Haiti–New Orleans African diaspora cultural identity with provocative historical, spiritual, and artistic linkages that began in the nineteenth century and persist today. Hurston’s publications on New Orleans Vo dou, Mules and Men and “Hoodoo in America,”1 offer important primary source material for analysis of this Haiti–New Orleans Vodou connection and its significance for the second-line theme of this volume.2

Through the memory of folklore, Hurston explicates in Mules and Men the complex religious domain of second-line culture, namely, the secretive world of early-twentieth-century New Orleans Vodou. She uses the highly original strategy of “folkloric performance” to re-create the rich vernacular language “rhythms” of the black community (which are central to second-line musical performances) and their connections to the geo-historical roots of New Orleans as an important circum-Atlantic city. Her narratives of the nineteenth-century Vodou queen Marie Laveau and the weekly Congo Square festivals—with their roots in Haitian and West and Central African spirituality—embody historical memories of slave resistance in New Orleans that continue to influence the political expression in second-line performances. Hurston’s “performative representations” of her own initiation in Mules and Men is a powerful case study of how second-line culture encompasses and expresses significant aspects of the religious tradition of Vodou.3

Recently Hurston’s work has been the subject of critical analysis in African American theological and religious studies. Katie G. Canon analyzes Hurston’s use in her novels of the folk culture and values of the black church as a model for “black theological ethics” and “the moral wisdom of black women.”4 Donald H. Matthews explores Hurston’s research methodology as an early model for “the African-centered approach to the interpretation of African-American” cultural, theological, and literary studies.5 Theophus Smith demonstrates how the Bible served as “a magical formulary” in Hurston’s folklore research.6 And, finally, Anthony B. Pinn sketches the history of Vodou in Benin, Haiti, and New Orleans, and discusses Hurston’s fieldwork as a way to rethink the canon of black religion in black theological studies.7

Pinn’s Varieties of African-American Religious Experience, which reveals the “rich diversity of black religious life in America” by focusing on non-Christian “popular religious practices and sites,” informs the African diasporic orientation of this volume. Two canonical issues that orient Pinn’s research are central for understanding Hurston’s unique contribution to black religious history in her time: the “narrow agenda and resource base of contemporary” black religious studies; and the “contention that African-American religious experience extends beyond … [the] institutional and doctrinal history” of Protestant Christianity to include Islam and African diasporic ancestral traditions.8 Indeed, these key issues are reflected in the religious meaning of Hurston’s research and initiation into Vodou in New Orleans and Haiti. She was seventy years ahead of her time in her exploration of the enduring connections between American religions and African diaspora traditions, and in her analysis of the power and richness of urban folk religions and Creolized synthetic-religious identities that stand on their own ground. Hurston’s interests reflect the current paradigmatic shift in religious studies toward an “ethnographic description of individuals and the groups with which they affiliate,” as exemplified in the works of Walter F. Pitts, Karen McCarthy Brown, and Robert Orsi.9

Zora Neale Hurston and New Orleans Vodou: The Haitian Concept of Knowledge, Konesans

New Orleans is now and has ever been the hoodoo capital of America. Great names in rites that vie with those of Haiti in deeds that keep alive the powers of Africa.

ZORA NEALE HURSTON, MULES AND MEN

In 1928 Hurston received a bachelor’s degree in anthropology from Barnard College, and in August of that year she traveled to New Orleans to begin six months of intensive fieldwork among the city’s Vodou adepts. She was a student of the renowned anthropologist Franz Boas at Columbia University. It was her spiritual experiences in New Orleans Vodou, however, that transformed her from a mere participant observer and collector of folklore to an initiate observer, deeply involved in the key themes and esoteric knowledge and rituals of the religion.

Previous studies of Hurston’s New Orleans fieldwork minimized the depth of “her angle of vision” as an initiate to focus on her work ex clusively “as anthropological documents … and literary texts.”10 Although I do not contest the validity of prior scholarship, I look to another provocative subject of analysis that is embedded in the study of Vodou as an African diasporic religious tradition with deep roots in Haitian spirituality. I analyze Mules and Men as a parallel expression of the Haitian konesans, which originates in the spiritual experiences of initiates and mystics and is expressed intuitively in the healing and magical rituals of the religion. Hurston’s record of esoteric knowledge in both Mules and Men and “Hoodoo in America” is an important primary source of information about New Orleans Vodou in the early twentieth century and its connections to Haitian Vodou.11 This esoteric magical and healing practice is also central to our understanding of the religious domain of second-line culture and its relations to circum-Atlantic performance in West Africa and Haiti.

The Haitian scholar Milo Rigaud sheds light on Vodou’s magical, esoteric practice embedded in the meaning and idea of the word “Voodoo”:

Voodoo encompasses an exceedingly complex religion and magic with complicated rituals and symbols that have developed for thousands of years … everything essential to the knowledge of the mystery is implicit in this word…. Vo means “introspection” and Du means “into the unknown.” Those who indulge in this “introspection” into the mystère (mystery) will comprehend not only the Voodoo gods, but also the souls of those who are the adepts and the servants of these gods. This is the only way in which the fruitful practice of the rites is possible to produce supernaturally extraordinary phenomena or magic.12

In Mules and Men Hurston clearly views magic as the centerpiece of New Orleans Vodou:

Belief in magic is older than writing. The way we tell it, Hoodoo started way back there before everything. Six days of magic spells and mighty words and the world with its elements above and below was made. And now God is leaning back taking a seventh day rest.13

This statement situates New Orleans Vodou in the realm of the profound and ancient mysteries of the religion that Haitian adepts such as contemporary visual artist André Pierre acknowledge as “a world created by magic.”

The Vodou religion is before all other religions. It is more ancient than Christ. It is the first religion of the earth. It is the creation of the world. The first magician is God who created people with his own hands from the dust of the Earth. People originated by magic in all countries of the world. No one lives of the flesh…. The spirits of Vodou are the limbs of God.14

In Hurston’s religious narrative, Mules and Men, Moses is the first and most powerful Vodou spirit, because he received God’s magic rod and acquired knowledge of ten of God’s powerful words from the snake resting under God’s feet during the creation of the world. This narrative is not just a folkloric transformation of a biblical story into “a conjure story,”15 as Theophus Smith writes, but instead is another path—“performative representations” of black vernacular oral tradition—through which Hurston establishes the Haiti–New Orleans Vodou connection in the realm of konesans.16

David Todd Lawrence contends that Hurston’s “performative representations,” namely, “her ‘between story’ exchanges” and interpretations in Mules and Men, “are the most valuable part of the entire book because they represent the performer in context in the act of performing for an audience … and enable us to understand the possibility of when and where a particular kind of folklore element might be employed over a long period of time.”17 Thus Hurston’s information about the oral tradition of New Orleans Vodou in her time establishes “a predictive cultural pattern”18 essential to an understanding of how subsequent second-line performance groups express important aspects of the oral culture of African diaspora religions over time.

In her later work, Tell My Horse, she explains the religious meaning of the folk stories of Moses’s magic as “Damballah Ouedo … the supreme mystère” whose “signature is the serpent.” From the time of the nineteenth-century Vodou queen Marie Laveau19 to the present in New Orleans Vodou, Danbala Wedo has been a constant lwa (Vodou spirit) involved in rituals as “the ancient sky father [arched] across the sky as a snake beside his rainbow wife, Ayida Wedo. He is the origin of life, and the ancient source of wisdom.” According to Hurston, however, in Haitian Vodou Danbala Wedo always has been one of the pantheons of lwa:

In the Voodoo temple or peristyle, the place of Damballah, there also must be the places of Legba, Ogun, Loco, the cross of Guedé who is the messenger of the gods, of Erzulie, Mademoiselle Brigitte and brave Guedé. Damballah resides within the snake on the altar in the midst of all these objects.20

The current scholarly consensus established by Patrick Bellegarde-Smith’s research and other groundbreaking studies of Haitian Vodou is that a synthetic, not syncretic, relationship exists between Vodou as a powerful African diaspora religion of resistance to Western hegemony and Christianity.21 Vodou stands alone, independent of mainstream Christianity. Hurston acknowledged this important synthetic quality of Vodou in New Orleans and Haiti, as she writes in Tell My Horse:

The Haitian gods … are not the Catholic calendar of saints done over in Black…. This has been said over and over in print because the adepts have been buying the lithographs of saints, but this is done because they wish some visual representation of the invisible ones, and as yet no Haitian artist has given them an interpretation or concept of the lwa. But even the most illiterate peasant knows that the picture of the saint is only an approximation of the lwa.22

In Mules and Men, the African ancestral tradition, called “hoodoo” and “conjure” by early-twentieth-century New Orleans black folk, is not a mere footnote to African American religious history. In Hurston’s work, the secrecy and centrality of Vodou in the religious life of New Orleans suggest that the religion’s esoteric knowledge and power is just as strong there as in Haiti:

Hoodoo … is burning with all the intensity of a suppressed religion. It has thousands of secret adherents. It adapts itself like Christianity to its local environment, reclaiming some of its borrowed characteristics to itself…. It is not the accepted theology of the nation and so believers conceal their faith.23

In her Vodou trilogy—Mules and Men, “Hoodoo in America,” and Tell My Horse—Hurston maps New Orleans as a significant religious site not only because of its relationship to black southern conjure and root work but, more important, for its connection to the Creolized fragments of Haitian culture and spirituality that lie deep in its history. Thus New Orleans is writ large on the map of black religion as a magical African diaspora city, which, like Haiti, has successfully resisted the efforts of mainstream Christianity to absorb its esoteric African ancestral knowledge.24

Haitian and New Orleans Vodou: Early Historical Connections in Congo Square

In “Hoodoo in America,” Hurston traces the early historical encounters between Haitian and New Orleans Vodou in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries:

[Vodou] has had its highest development along the Gulf Coast, particularly in the city of New Orleans and in the surrounding country. It was these regions that were settled by the Haytian emigrees at the time of the overthrow of French rule in Haiti by L’Ouverture. Thousands of mulattoes and blacks, along with their ex-masters were driven out, and the nearest French refuge was the province of Louisiana. They brought with them their hoodoo rituals, modified of course by contact with white civilization an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction to the New Edition

- Selected Bibliography for the New Edition

- Introduction: Follow the Second Line

- 1 The Haiti–New Orleans Vodou Connection: Zora Neale Hurston as Initiate Observer

- 2 Mardi Gras Indians and Second Lines, Sequin Artists and Rara Bands: Street Festivals and Performances in New Orleans and Haiti

- Interlude: The Healing Arts of African Diasporic Religion

- 3 In Rhythm with the Spirit: New Orleans Jazz Funerals and the African Diaspora

- Epilogue: A Jazz Funeral for “A City That Care Forgot”: The New Orleans Diaspora after Hurricane Katrina

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index