- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

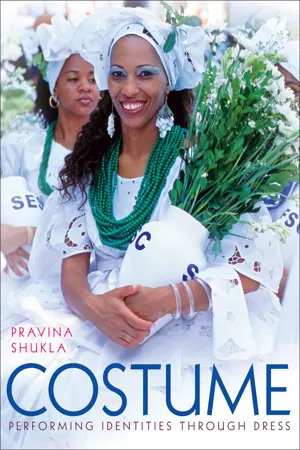

A revealing look at how and why we dress up for events from historical reenactments to Halloween, with an "engaging writing style and rich illustrations" (

Choice).

What does it mean to people around the world to put on costumes to celebrate their heritage, reenact historic events, assume a role on stage, or participate in Halloween or Carnival? Self-consciously set apart from everyday dress, costume marks the divide between ordinary and extraordinary settings and enables the wearer to project a different self or special identity.

In this fascinating book, Pravina Shukla offers richly detailed case studies from the United States, Brazil, and Sweden to show how individuals use costumes for social communication and to express facets of their personalities.

"Revelatory . . . a wide-ranging book bringing attention to clothing as part of festivals and folk heritage events, pop culture conventions and dramatic performances." — Nuvo

What does it mean to people around the world to put on costumes to celebrate their heritage, reenact historic events, assume a role on stage, or participate in Halloween or Carnival? Self-consciously set apart from everyday dress, costume marks the divide between ordinary and extraordinary settings and enables the wearer to project a different self or special identity.

In this fascinating book, Pravina Shukla offers richly detailed case studies from the United States, Brazil, and Sweden to show how individuals use costumes for social communication and to express facets of their personalities.

"Revelatory . . . a wide-ranging book bringing attention to clothing as part of festivals and folk heritage events, pop culture conventions and dramatic performances." — Nuvo

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Costume by Pravina Shukla in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Customs & Traditions. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

FESTIVE SPIRIT

Carnival Costume in Brazil

AT THE POINT WHERE LATIN AMERICA AND AFRICA COME CLOSEST, Portuguese explorers landed on the shores of Bahia in 1500. Within half a century they had established Brazil’s first colonial capital in the port city of Salvador and brought enslaved people from Africa to work the land. A Catholic country with the largest African population in the diaspora, Brazil has more people of African descent than any country except Nigeria, the most populated of the African nations.1 The slave trade was officially abolished in Brazil as late as 1888, resulting in a large population of formerly enslaved and recently arrived people who entered the country largely through Salvador da Bahia. Intermingling in the New World, people of astonishing cultural diversity created the Candomblé religion: a syncretic mix of African and European faiths, gods, and practices. Yoruba orixás—many of them deified ancestors—became the African gods most often worshipped in Brazil, each one closely associated with a Catholic saint. The complex Afro-Brazilian identity—at once Catholic, African, and Brazilian—is on display in the public events of Salvador. Identity, history, race, religion, and political and social affiliations are all communicated visually by the clothing worn in festivals and by the costumes of carnival.

A spectacular sight in Salvador, one often reproduced in postcards and posters, is the “tapestry of white”: a mass of men parading on the streets dressed in the all-white costume of the group Filhos de Gandhy. The men, ten thousand strong during the carnival parade, each wear a long white tunic, sleeveless and ankle-length; a terry-cloth bejeweled turban; blue socks and white sandals. Their ensembles are lavishly embellished with beaded necklaces, sashes, ribbons, raffia, and armbands of cowry shell. They are present at the secular carnival parades and at the sacred festivals that honor Catholic and Candomblé saints. The iconic costume is a text that appears in different social contexts, and it can be used to tell the complicated history of this place, signaling the solidarity, resistance, and defiance of the Afro-Brazilian population.

I observed and documented the summer festivals and the carnival of Salvador in 1996, 1997, and 1998, talking to many members of the carnival group (bloco) Filhos de Gandhy. In 2007 and 2009 I returned during the off-season for in-depth interviews with the leaders of the bloco. To deepen my understanding of the philosophy, aesthetics, and costumes of Filhos de Gandhy, I spoke with three principal members of the directorate: the fiscal officer, Ildo Sousa; the artistic director, Francisco Santos; and the elected president of the group, Professor Agnaldo Silva. Having grown up in Brazil, my first language is Portuguese, and I spoke comfortably with the three men during the informative conversations I translate below.

FILHOS DE GANDHY

The oldest and most respected carnival group in Salvador is the all-male group Filhos de Gandhy, literally “Sons of Gandhi,” founded in 1949, the year after Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated in India. The bloco was started by a small number of unionized stevedores under the leadership of Durval Marques da Silva, known as Vavá Madeira. Gandhi’s death inspired the dockworkers to form a carnival group and to name it after the great leader who fought racial injustice in India and who could serve as a model for the Afro-Brazilian struggle against discrimination, especially in Salvador. The bloco is currently headquartered in the historic center of the city, Pelourinho, literally “the Pillory,” where slaves were once whipped. Memories of violence linger today; as the novelist Jorge Amado, who was born in Bahia and lived in Salvador, wrote: “These mansions of Pelourinho are full of tormented cries; this slope is full of grief, of a suffering that continues to this day among the modern slaves of this disenfranchised place.”2 Today Pelourinho is a UNESCO world heritage site, a place of glorious baroque churches, its streets lined with small Portuguese houses strung in rows, picked out with color—pink, peach, blue, green—and stylishly ornamented.

Pelourinho, Salvador da Bahia, Brazil, 2007.

The group is now officially called Associação Cultural Recreativa e Carnavalesca Filhos de Gandhy, meaning they do more than parade during carnival. They also have a religious, cultural, and social presence in the city throughout the year that climaxes with the grandiose visual spectacle at carnival time.

Elsimar Lima buying sunglasses for the opening parade by Filhos de Gandhy. Carnival, Salvador da Bahia, Brazil, 1998.

The men of Filhos de Gandhy—exotic, beautiful, and bejeweled—are known for their flamboyant costume. The ensemble that Professor Agnaldo called a “kit” in Portuguese includes the garment, shoes, and accessories. The garment is an extra-long, white T-shaped tunic with that year’s theme and motifs screen-printed in blue on the front. The design varies slightly from year to year, and it always states the year’s theme and carries a drawing of Mahatma Gandhi with the attributes of the orixás around him. The participant—the associado—receives a pair of socks, usually blue, and a pair of plastic strappy sandals, usually white, with the word “Gandhy” printed on them. The tunic is tied at the waist with a blue sash, adjusted for the height of the wearer, and any extra fabric is puffed out over the belt. Also included is a pair of blue ribbons that pinch the fabric over the shoulder seams, tied into two symmetrical bows. The “costume kit” also comes with a white cotton towel, measuring two feet by four feet. Each member of Filhos de Gandhy will have the towel sewn into a turban. Right before the carnival, one sees dozens of men patiently sitting on chairs outside the headquarters having their turbans custom-made. A cotton drawstring bag, a handkerchief, and a white spray bottle of lavender-scented alfazema complete the kit.

Seeking to learn the history of the bloco from its current leader, in 2009 I met with Professor Agnaldo Silva in his office in the group’s headquarters in Pelourinho for a long morning interview.3 A retired teacher of chemistry, physics, and mathematics, he was at that time serving his fourth term as president of the group, to which he has belonged since 1976. Professor Agnaldo explained to me the social responsibilities of Filhos de Gandhy, including that of officially welcoming dignitaries—government officials and important national and international visitors. A small delegation of Filhos de Gandhy members, dressed in costume and playing instruments, is regularly dispatched to the Salvador airport to receive guests, and in August 2010 the president of India, Pratibha Patil, was welcomed to Salvador by a group from Filhos de Gandhy that included President Agnaldo Silva and Vice President Israel Moura.4 The professor said that visitors to Salvador are charmed by the visual beauty of Gandhy, charmed by the rhythm of their instruments: the atabaque (drum), agogô (bells), and xequerê (bead-covered gourd). He said that Filhos de Gandhy is symbolic of Bahia, the cartão postal (postcard) of Salvador: “We have Filhos de Gandhy to represent Bahia.”5

What makes Filhos de Gandhy appealing in the eyes of tourists and dignitaries is this mix of Africa and India. Africa provides the foundation for the bloco through music, dance, and rituals; India provides the ornamental charm through its fantastical costumes. In fact the Afro-Brazilian religion of Candomblé has always been basic to the bloco. Shortly after I had met him for the first time, during the first few minutes of my interview with Francisco Santos, the costume designer and artistic director of Filhos de Gandhy, he said to me, “We pay homage to Mahatma Gandhi, right, but there is a deep link between the history of Gandhy and Candomblé. The majority of the people who parade with Gandhy are people of Candomblé; do you understand?” Since its very inception, Candomblé has played a central role in the definition of the bloco. Ildo Sousa told me that the period of the founding of Filhos de Gandhy, in the late 1940s, was a time in Salvador when “the racial segregation was very evident. Very strong. And these stevedores, they, all of them, were practitioners of Candomblé.” He explained that then, unlike now, Candomblé was a “persecuted religion, persecuted by the police” and hidden from view.

African cultural resistance is the deep message that the group communicates to the city and the world. By using the Mahatma as a peaceful foil, these men aggressively insert African religion into the cultural fabric of Salvador and Brazil. This is akin to the Mardi Gras Indians, who use their glitzy, beautifully beaded Native American regalia to expose the history and contemporary reality of African American life in New Orleans.6

A collection of oral history interviews with the original founders of Filhos de Gandhy—Anísio Félix’s Filhos de Gandhi: A História de Um Afoxé (Filhos de Gandhi: The History of an Afoxé)—published in 1987, reveals that from its inception most of the original members were “people of the axé,” practitioners of Candomblé whose aim was to spread the religion through the streets. Humberto Ferreira Café, stevedore and former president of the General Assembly of Filhos de Gandhy, frankly says, “Gandhy was founded with the objective of divulging on the streets the Candomblé religion.”7 During those initial years the group was classified by the carnival officials as an afoxé in acknowledgment of its religious rhythms and music. The Yoruba word “afoxé” translates as “powerful incantations.”8 Afoxés in Salvador are groups that chant in African languages; that play percussive instruments, especially the agogô bells, atabaque drums, and xequerê beaded gourds; and whose colors and symbols have meaning within the system of Candomblé. By parading in public, practitioners introduce and expose the unknowing to their religion, so afoxé is often called the “Candomblé of the streets.” The first afoxé group paraded in Salvador in 1895, but they soon disappeared from public view as a result of the police persecution of Candomblé. (Candomblé gatherings in Salvador required prior registration to obtain police permits until 1976.)9

Professor Agnaldo told me proudly, repeating himself for emphasis, that the group is in the Guinness Book of World Records as the largest afoxé in the world. He said the founders of Filhos de Gandhy wanted music to accompany their theme of peaceful nonviolence, but Indian music—the chants and clanking bells of Hare Krishna—did not seem suitable for carnival, so they chose to play the sounds of ijexá, whose slow, rhythmic and leisurely tempo went with the Indian costume and harmonized with their peaceful stroll.

Ijexá is a nation of Candomblé. The beats of the atabaque, of the agogô, of the xequerê, is afoxé, meaning, Candomblé of the streets. Afoxé means Candomblé of the streets. Based on this Candomblé of the streets, they formed this afoxé and sang the songs of praise for the orixás.

So, in truth, we have to associate Candomblé with India. That is why we call ourselves “Hindu-Africa.” We are Afro-descendants, we are of African origin, and Candomblé is of African origin. And we follow the philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi and its advocacy of peace.

For us, in the religious syncretism of Candomblé, it is Oxalá who is our chief god. Oxalá is he who wears white, who advocates for peace. And Mahatma was a pacifist who sought peace. So, together, we associate Mahatma Gandhi with Oxalá, who is the chief god for us.

Filhos de Gandhy venerate the Yoruba god Oxalá by playing afoxé music, bringing Candomblé sounds and praise songs out of the terreiro temple into the streets, and, in particular, by playing the rhythms of ijexá, a set cadence associated with specific orixás, including Oxalá. The chief god of the Yoruba pantheon, the creator of the world, known as Obatala in Nigeria and Oxalá in Brazil, gains visual presence through the possessed bodies of his worshippers—his sons and daughters—for the initiates consider the orixá their father, referring to him as “my father Oxalá”—o meu pai Oxalá. This principal god is always shown in white vestments, hunched at the waist, since he bears the burden of the world on his shoulders. He is committed to peace and renounces violence. In his hand he carries the paxoró, a staff resembling a multi-stacked umbrella, and his symbol is the white dove.10 His association with peace makes the connection to Mahatma Gandhi obvious. In a large painting by Francisco Santos, Gandhi is held on the shoulders of the male orixás of war and thunder, Ogum and Xangô. Gandhi, as Oxalá, wears a white robe and the blue and white beads of Filhos de Gandhy; he carries the globe in his right hand, the paxoró in ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction Special Clothing for Extraordinary Contexts

- 1 Festive Spirit Carnival Costume in Brazil

- 2 Heritage Folk Costume in Sweden

- 3 Play The Society for Creative Anachronism

- 4 Reenactment Reliving the American Civil War

- 5 Living History Colonial Williamsburg

- 6 Art Costume and Collaboration on the Theater Stage

- Conclusion Costume as Elective Identity

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index