![]()

1Bob Taylor: Stories in Wood and Words

Re-membering, then is a purposive, significant, unification, quite different from the passive continuous fragmentary flickerings of images and feelings that accompany other activities in the normal flow of consciousness . . . A life is given shape that extends back in the past and forward into the future. It becomes a tidy edited tale.

(Myerhoff 1992:240)

Introduction

In the fall of 2013, the Columbus Area Arts Council invited me to present a workshop on “Folk Art and Aging” at the Mill Race Center, an active-senior facility that offers a robust range of classes and workshops for area retirees. I agreed, hoping to solicit feedback on my research and ideas. While going over my presentation at the center before others arrived, a tall, thin man poked his head into the room. I invited him in and introduced myself. “What do you have there?” I asked, pointing to the two boards wrapped in towels that he had brought for the show-and-tell portion of the evening’s program. “I do memory carvings,” he explained as he unpacked the boards. On the surface of each, he had carved detailed scenes from his childhood; the pair of boards visually told the story of a train trip in 1941 that the elder, Bob Taylor, took with his parents to Coney Island in Cincinnati, Ohio. I was impressed at the artist’s mastery of his craft and the narrative details invested in these panoramic panels.

“How long have you carved?”

“Since I was eight years old or so, but didn’t start doing the memory carvings until after I retired.”

My head raced with questions for the carver, but the room was beginning to fill with more workshop participants. “I want to talk to you more,” I said, “but I have to finish getting ready for the program. Can we talk afterward?”

Several seniors brought examples of their needlepoint, quilts, woodcarvings, and other handmade works, which they took turns sharing throughout the evening. Though Bob had brought tabletop stands to display his two carvings, he placed the boards face down on the table, concealing their beauty. When it came time for him to share his work, he stood and addressed the room: “Since I have been retired, I’ve been doing memory carvings of my childhood.” Then he lifted the boards and placed them on the stands, revealing the complex carved scenes (figure 1.2). The audience’s amazement was audible as they oohed and aahed. He then began to tell the story of his childhood trip to Coney Island and his process of researching and making the panels to commemorate it. “The trip that I brought to show was a trip that we took in 1941 in June,” he began. He then outlined the event based in part on his childhood recollections:

We got on a train in Columbus. We went to Cincinnati; they met us with buses; took us down to the docks. We got on a riverboat and we went to Coney Island, which was about fifteen miles east of Cincinnati.

[Cummins] gave us ride tickets. We packed a lunch, which we ate. I think we ate it on the boat . . . but I was eight and a lot of this was really foggy, so I had to go back and do research.

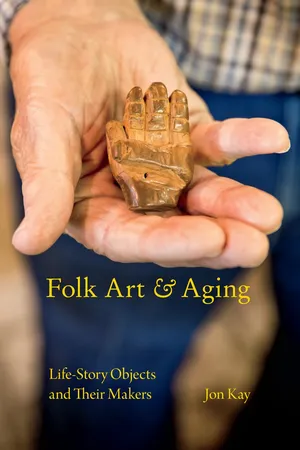

Fig. 1.1 Bob Taylor in his workshop holding his dead whale carving in Columbus, Indiana. Photograph by Greg Whitaker Photography, 2015.

Then he recounted his quest to reclaim the details (and eventually the story) behind his murky childhood memories.

In order to create his scenes, Bob searched for additional information and visual clues about that long-ago trip. He talked with local historians and newspaper columnists, who finally led him to a local woman who had been on the trip and was a few years older. She shared her memories of the day and let him make a copy of a souvenir brochure about the excursion. From his recollections, the brochure, as well as a handful of family photographs from the outing, Bob compiled his set of memory carvings.

Fig. 1.2 Bob Taylor at the Mill Race Center, Columbus, Indiana, 2013.

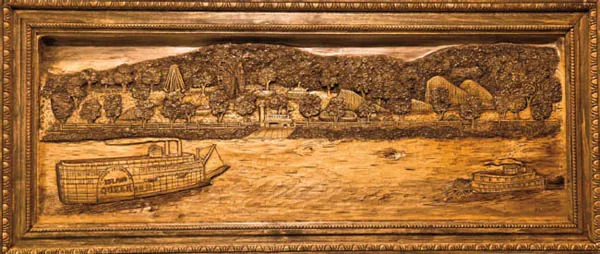

The pair of panels tells the two phases of the Coney Island trip. The first shows his family ready to board the train behind the Cummins Building in Columbus. His grandfather, brother, mother, and father are waiting with him, while a brass band plays (figure 1.3). The second panel shows them arriving at Coney Island and includes the Island Queen, the steamboat that ferried them on the river; the Ferris wheel, rollercoaster, swings, and a merry-go-round in the amusement park are shown in the distance (figure 1.4). He even includes a coal barge that his father just happened to snap a picture of that day. The artist’s scenes are beautiful compilations of remembered moments and discovered images.

After the presentation, Bob gave me his telephone number, and a week later, I was sitting in his workshop in the basement of his Tipton Lake home in Columbus. He talked about growing up in the midsize town, his lifelong practice of carving, and the personal panels he creates to record childhood memories.

Carver of Memories

As Mary Hufford and other scholars have noted, not all autobiographies “take the form of books,” but rather some of the folk-art projects of older adults are “a kind of three-dimensional reminiscence for their makers whereby the past bursts into tangible being” (1984:33). But these works are not just “reminiscence” or the recalling of the past, but rather thoughtfully constructed material life-stories. In many ways, Bob Taylor’s art is the product of a life of carving and remembering. He blends his gift of storytelling with his love of woodcarving to produce striking narrative scenes about special moments when he was young.

Fig. 1.3 Bob Taylor’s Excursion Train to Coney Island displayed at the Mill Race Center, Columbus, Indiana.

Fig. 1.4 Bob Taylor’s Coney Island river trip panel displayed at the Mill Race Center, Columbus, Indiana.

While just a boy, Bob received his first pocketknife from his grandfather. He recalls:

My grandfather gave me my first pocketknife. It’s a red-handled knife. I could get it out of my case there [pointing to his workbench]. Eight years old—I don’t know how many people today give their child a knife when they’re eight years old—probably not too many . . . [My grandfather] could see that I was interested. I had already made a little animal or two. So for Christmas one year he gave me a red-handled pocketknife.1

Although receiving the red-handled pocketknife started the youth down the path of becoming a woodcarver, his grandfather was not Bob’s only carving influence.

Around eleven years old, Bob met legendary carver Mooney Warther.2 Known for his speed at making wooden pliers and for carving intricate scale models of steam locomotives, Warther set up his traveling woodcarving museum at the Bartholomew County Fair. Bob tells of the carver’s demonstration and exhibit that he saw nearly seventy years ago:

We used to go to the fair . . . and just inside the gate, the year that I remember, there was a man. He had a truck and it had a board that let down from the side to make like a stand that he could come out, or a platform where he could come out and talk to the people—a little bit higher than what the people were. And he would come out on the platform with his pocketknife and piece of wood and he would make a few cuts in his piece of wood and make a pair of pliers. And I thought that was cool. I really liked that. I wanted to see him do that again. Well, my folks said, “No, we’re going to go look at the 4-H exhibits,” which weren’t too far from there. And they said, “Okay, well, you just stay right here and we’ll pick you up once we come out of the exhibits.”

Okay. So I’m waiting for this gentleman to come out again onto the platform. The people that had been in the crowd had gone through the exhibit then and paid a nickel or a dime, whatever it was, to see what was in the truck. And so as they left, a few minutes later he came back out on the platform and saw me standing there. He said, “Can I help you, son?” And I said, “Well, I want to see you do that again.” And he said, “Well, would you like to see what’s in the truck?” And I said, “I’d love to.”

So he came down off the truck, took my hand, led me through the exhibit. And it was the most [unbelievable] things I had ever seen that anybody could do. These were train models that were made out of ebony and ivory and walnut and bone. And so I came back to the front of the exhibit there and met my folks, and of course it worked well because then once I told them what was in the trailer, they had to go, too. And they had to pay the nickel or dime, whatever it was. So, but it was well worth it.

With the knife his grandfather gave him and the inspiration from Warther’s traveling museum and show, carving became a passion for the fledgling artist.3 Bob learned to carve in a variety of styles. As a young Boy Scout, he practiced making neckerchief slides and whittling animals, which helped him develop as a carver.

Once grown, Bob apprenticed as a patternmaker and spent more than twenty years working “on the bench” as a master patternmaker. From engineers’ drawings, he carved wooden, three-dimensional prototypes of truck parts, missile components, and many other products. From these patterns, manufacturers produced the molds needed to make metal castings. The last twenty years of his working life, the carver sold patterns internationally for Badger Pattern Works in Milwaukee. However, whether on the bench or off, Bob continued to carve for his own enjoyment.

When his children were young, Bob served as a Boy Scout leader and whittled whimsical neckerchief slides that were even more elaborate than the ones he made when he was young. He remembers, “I always had a sharp tool in my hand doing something, and still do today.” Having retired from patternmaking in 1999, he now dedicates much of his carving time to researching and making his memory projects.

Landscape Relief Carving

Bob invests months into researching and designing each memory carving before he ever puts chisel to wood. He enjoys researching the forgotten facts and visual elements that he incorporates into his scenes. An important part of his creative process, the time spent researching locations, people, and events not only informs his designs, but also provides him with additional stories to tell about his panels. As the narrator of his completed carvings, he easily shifts from sharing a childhood memory to talking about uncovering additional information for his scenes.

As I will show throughout this book, elders who make life-story objects often engage in a process of personal discovery and creative expression, frequently followed by a series of presentations or narrations of their creations. Joanne Stuttgen observed:

By making things, men and women review, reshape and reorder their lives and themselves. The process of manipulating physical materials to reshape disrupted lives is a reversal of ritual, a process in which chaos is inverted and systematically and symbolically arranged. (1992:304)

In Bob’s memory carvings, he unites the disparate shards of memories and discovered details into a cohesive recalled world through which he constructs his tight narrative scenes and tells his personal stories.

Once Bob has researched the facts and found period photographs or other relevant visual data, he makes several detailed sketches of his scene. From these illustrations, he compiles a master drawing that renders all of the buildings, cars, trees, and other visual elements to the size they will appear in the completed carving. He tapes this pattern to the top edge of the board to be carved, so that he can easily lift the paper as he works on his relief carving. Using carbon paper, he then traces the complete drawing onto the board and begins to carve. With a gouge and chisels, he removes the traced lines from the wood, first taking away the deepest sections to develop the different depths in the scene. Once he develops these visual levels, he resketches his pattern onto the panel, adding the final elements to his scene. With his chisels, gouges, and mallet, he then painstakingly carves the fine details of his remembered landscape.

Bob’s aesthetic aim through this complex process is to make an attractive panel that contains the necessary elements of his story; however, the image must also be as visually accurate as possible. Whether the St. John’s Church at White Creek or the Cummins Building in downtown Columbus, each panel evokes the essence of a place so that others can recognize its location. He explains that while the carvings are not “an exact perfect scale model,” they do capture “what people remember in their minds.”

Although Bob works in a variety of genres, his memory pieces employ a relief style of carving appropriate for landscape scenes. Rupert Kreider (1897–1983), an itinerant carver from Pennsylvania, inspired Bob’s approach. Kreider often passed through Bartholomew County, Indiana, where he found work on local farms. Bob never met the carver, but he bought one of his wooden scenes from an antique shop in Hope, Indiana, in 1981. The panel profoundly changed Bob’s approach to carving. He recalls:

It was the inspiration of looking at that piece that gave me the desire to want to figure out how he was doing what he was doing . . . I studied the piece, made some tools, studied some more, did some samples and so forth, and finally figured out what Rupert was doing to make his carvings.

Kreider’s art piqued Bob’s creative interest, and he wanted to find out as much as he could about the artist and this distinctive technique, and hoped to see more of his work.

The woman who sold the carving to Bob told him her memories of Kreider’s time in Indiana. She recalled that one time when the carver was passing through Bartholomew County, he stopped at her family’s farm to ask for a drink of water. Her mother offered him food, and her father let him stay in the barn overnight. Kreider e...