- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In a forthright and uncompromising manner, Olúfémi Táíwò explores Africa's hostility toward modernity and how that hostility has impeded economic development and social and political transformation. What has to change for Africa to be able to respond to the challenges of modernity and globalization? Táíwò insists that Africa can renew itself only by fully engaging with democracy and capitalism and by mining its untapped intellectual resources. While many may not agree with Táíwò's positions, they will be unable to ignore what he says. This is a bold exhortation for Africa to come into the 21st century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

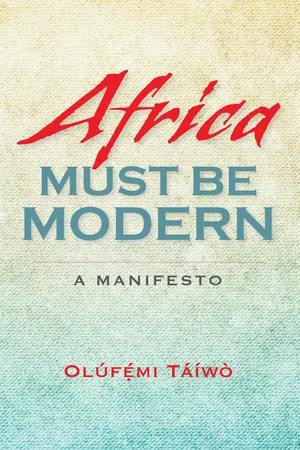

Yes, you can access Africa Must Be Modern by Olúfémi Táíwò in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

TWO

The Sticky Problem of Individualism

Why are Africans hostile to individualism, the dominant principle of social ordering and living under modernity? There are diverse possible answers but, in light of our primary focus on modernity, a case can be made for the fact that much of the hostility directed at individualism originates from the conflicted legacy of modernity and colonialism in the continent.

I WOULD like to begin by offering a variation on a Yorùbá proverb: “If you wish to see the red of an African intellectual’s eye, that is, draw the ire, especially of an academic, merely suggest that the continent and its peoples come to grips with the idea of individualism and all that it entails.” One can only imagine what might follow a suggestion that Africans embrace individualism as a principle of social ordering. What this means is that for African intellectuals, individualism and all that it entails are fighting words, the utterance of which is likely to be followed by testiness, frostiness, hostility, sometimes abuse and, in the worst of cases, verbal violence. Yet, I would like to insist in this chapter that it is way past time that Africans, especially their intellectuals, engaged with and embraced, yes, embraced individualism and some of its manifestations. This looks simple enough. Yet, it is almost impossible to have any decent debate about this among Africans.

Again, I cannot, and I am not inclined, to claim that I would be the first African scholar to canvass a deep understanding of or engagement with individualism. I doubt, though, that there have been too many advocates for the sort of stand taken in this section. I would like to argue that the long-standing opposition to individualism and to most of its ramifications in the African imaginary must abate if Africa is to move forward with the rest of the world.

Why are Africans hostile to individualism, the dominant principle of social ordering and living under modernity? There are diverse possible answers but, in light of our primary focus on modernity, a case can be made for the fact that much of the hostility directed at individualism originates from the conflicted legacy of modernity and colonialism in the continent. African scholars love to tell stories of African communalism, of how Africans are communalistic almost by nature, and how, beginning in the nineteenth century, what they have identified as “the African personality” is so different from other personalities in the rest of the world that they consider the assault on and near destruction of it under the combined onslaught of first Christianity and later colonialism as one of the signal losses suffered by the continent and its peoples under those alien historical movements.

This is how the narrative goes. Before the irruption of Christianity and colonialism into their land and mindscapes, communalism was the dominant and preferred mode of social living and principle of social ordering in much, if not all, of Africa. It is very difficult to locate clear and concise definitions of communalism in much of the writing about the idea. For our purposes, a rough characterisation should suffice. Communalism, in the present context, is the view that a people prefer to and predominantly live in community. Since this is not a peculiarity of any people but almost a defining feature of our basic humanity, it must be the case that communalism is intended to mean more than the commonplace we just stated. On this score, communalism is a mode of social living in which living together, communal living, is to be preferred. As well, it is a principle of social ordering under which, in the relationship between the individual and the community, the community is held superior to the individual, and where their interests come into conflict, those of the community should prevail. And it should not be forbidden to bend the will of the individual or sometimes abridge his or her interests if doing so would serve the ends of the community. In such a setting, the community and its interests are supreme, and it suffices to cite such interests to justify interfering with individual preferences even in those areas that relate to how an individual wants to be in the world and what he or she takes to be the good life and the means for attaining it.

It is said that the individual was not only recognised but was also accommodated and her interests and well-being were well protected and taken care of. We must not make light of this contention. Each one was her fellow’s keeper. Strangers were welcomed and provided with victuals and a place to lay their heads. Mothers took care of children. Actually, strictly speaking, what I just said is incorrect. The rearing of children was not tied to the matter of who bore them. Everyone, or at least every adult in the neighbourhood, took responsibility for the rearing of children in their vicinity, regardless of who bore them. Young mothers were not left alone to take care of themselves and their infant children. Wives took care of their husbands and their families; husbands did the same for their wives and the latter’s families. Building houses, clearing land, planting and harvesting crops were never the sole responsibility of any single individual. Each went to help others execute such tasks, and they in turn were there for each other when each individual’s own time came for help. In short, it is hard to argue that anyone would be left untaken care of in a context in which everyone was required to look out for and take care of other people in the community.

You are right to wonder, dear reader, where is the individual in all this? Of course, and this is the crux of communalism as a principle of social ordering, the individual is somewhere there in the mix. It is just that she is lost in the collective thicket. She is palpably inferior to the collective and few were those circumstances in which her interest or preference or say-so would trump those of the group or community. It is almost as if there is a pact between the individual and the community under which, in return for being taken care of by everyone else, the individual forgoes any significant exercise of will in the ordering of his life. In other words, the individual is accommodated insofar as he is willing to be subsumed in the embrace of the group. Meanwhile, all the other attributes of the individual remained intact: individual names, mine and thine, heroism, and so on. But, when all is said and done, the community rules and that’s that.

If Africans are to be believed, the arrangement worked quite well. Great nations rose and fell as in other areas of the world; people lived well and their communities prospered. There was very little, if any, destitution because when there was abundance it was shared, and when there was scarcity, it was shared as well. Everyone pulled for the success and prosperity of their communities. This pretty much is the story that Africans love to tell of their forebears before the killjoy foreigners came and put paid to the good old days.

Before we go on to consider in detail the new mode of social living and its attendant principle of social ordering that shook the African world out of its orbit, I would like to suggest that, no matter one’s preference, the story that we have been considering sounds too good to be true. Indeed, it is easy to see that it could only have been true of the simplest of societies marked by small size, undifferentiated populations and unanimity of opinions. That is, in the name of underscoring how different Africans and their culture are from the rest of common humanity, African scholars actually end up providing needless fodder for the cannons of anti-African racism. How do they do this? It is a fundamental pylon of racial supremacist discourse that Africans and their descendants in different parts of the world are either not a part of the human race or are so different from other humans that they are considered barely human. Every time African scholars and their overseas sponsors or sympathisers play what we call the “difference game” they reinforce this racist mentality. It is time to get rid of this game.

Once we get past the game and its surrogates, we find that there is no human society that, at a time closest to its inception, was not communalistic in its mode of social living. But any society with any degree of complexity would have begun to distance itself from the undifferentiated totality once it evolved a distinction between mine and thine. Does this mean that individualism immediately supplanted communalism as a mode of social living? By no means. The emergence of more advanced forms of social differentiation beyond that of mine and thine meant that even when communalism remained the dominant mode of social living, it did not remain the only principle of social ordering.

This is not the place to cash out the philosophical niceties suggested by these distinctions. What is of moment here is that in societies marked by high levels of social differentiation sometimes manifested in hierarchies marked by superordinate/subordinate relationships, it rings less true to speak only of horizontal relations marked by mutual concern and coordinate or complementary status. In such situations, we must expect some relationships characterised by inequality, marked by exploitation of some by others, whereby many produced surplus enough to enable some to live without having to work, and so on. If indeed Africans built complex civilisations that included sophisticated systems of governance, socio-economic division of labour, not to talk of complicated ideological structures, it stands to reason that even if they retained communalism as their principal mode of social living and dominant principle of social ordering, they must have embodied significant heterodoxy and difference among their diverse populations.

Hence, we must expect that in spite of all the good that is attributed to communalism over time, there must have been a minority of individuals who didn’t care much for the play of community and its overwhelming influence in their lives. That is, we can imagine that in those days of yore there were Africans who were contrarians, who sought to do things differently, who did not think that the ways of the community were the only or even the best ways of doing things, who desired to have a social arrangement that was more accommodating of individual preferences, and who could not wait to jump at the opportunities for these alternative ways of being human when first Islam and then the second wave of Christianity came ashore in their communities.

Certainly, the history of Christianity in Africa goes back to the very inception of the faith itself. But on the coast of West Africa and the rest of the continent outside of North and Northeast Africa, the introduction of Christianity followed different trajectories. The first wave of Christianity landed on the West and Southwest coast in the fifteenth century and fizzled out after a while. At that time, too, the missionaries tried to take advantage of the then communalism of African societies by converting African rulers in the hope that where the leaders led the rest would follow. It is a testimony to the resident heterodoxy in those societies that the project failed in all the places where it was tried.

Then came the nineteenth century and, in the aftermath of the abolition of Slavery and the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, a new wave of missionaries landed on the west coast of Africa. There were some fundamental differences between this latter movement and the former one described above. In the first place, the new Christianity is a post-Reformation variant which meant that instead of the previous Catholic version characterised by monopoly, there was a variety of protestant denominations competing for the souls of the African natives. Secondly, as a result of development during the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and the evolution of New World Slavery as well as the activities of the Humanitarian and Abolitionist Movement, there was a veritable African component in the new cohort of missionaries desirous of fishing for native souls. That is, a good part of the evangelisation undertaken from the nineteenth century on was driven by native agency which may, in part, explain its widespread and stupendous success.

Finally, this new variant of Christianity formed a good part of the genesis of, and in fact was barely distinguishable from, a larger movement: modernity. By that time, the modern age had come into its own and the basic tenets of modernity would become the ideological template for social transformation that the new evangelisation brought in its wake. These three characteristics are: (1) the principle of subjectivity; (2) the centrality of reason; and (3) the idea of progress. They combined to herald a new reality shaped by modernity and which, we argue, was stymied when colonialism was imposed on the continent beginning in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

One of the core tenets of modernity is the preference for individualism as a mode of social living as well as a principle of social ordering. It is this individualism that is at issue in the present discussion. This is the individualism that constitutes a sticky problem in African discourses, theories, and social practices. The mentioning of this idea is the equivalent of fighting words in discussions with African scholars. Although hostility is rife among Africans towards the ideas associated with individualism, there is little evidence that African scholars and sundry intellectuals have ever cared to unpack what these ideas entail and what might be good about them.

As is the case throughout this work, it is my contention that Africa would do very well indeed, first, if its peoples were to familiarise themselves with the idea of individualism and, second, embrace it in some measure as both a mode of social living and a principle of social ordering. Again, consonant with the general tenor of this manifesto, I take it that Africans do not need me to educate them on the ills and evils that attend individualism: they know them too well already and this knowledge explains their unease with and hostility towards it. Africans already know that under a mode of social living characterised by individualism, individuals are ravaged by loneliness, mutual hostility, lack of other-regarding concern, excessive pursuit of individual fulfilment even at the expense of the community and, in the twilight of their lives, such individuals are herded into old people’s homes where they are at the mercy of stranger caretakers who abuse them or, at a minimum, fail to extend to them the kind of loving tenderness that would have been theirs in a communalist-oriented social setting.

What is more, where individualism is the principle of social ordering, in the Africans’ understanding of it, the individual is prior and superior to the community and the interests of the community are routinely sacrificed to those of the individual. Where there is a conflict between the individual and the community, the individual often wins; the community is not permitted to bend the will of the individual to conform to communal preferences and the individual in her person, place, or plan of life may not be interfered with except at the invitation of the individual concerned.

Just as in the case of the communalist story, the story that Africans tell themselves of individualism, too, is somewhat off the mark. But let us even assume that the story is partly true—and I concede that it is—it does not in any way encompass the whole of individualism as both a mode of social living and a principle of social ordering. Here I would like to offer my fellow Africans an account of individualism as a core tenet of modernity that endeavours to present it in positive light and shows how Africa, as part of a positive critical engagement with modernity, will be prospered.

The modern idea of individualism, understood as a mode of social living, is built on a philosophy of separation. Communalism is founded on the affirmation of an organic connection among those who make up a human community. In the view of some African communalists such is the nature of this connection that to be an individual, a person, requires that one be connected with the community. Absent it, one is a nonentity. In the modern conception, on the contrary, individuals are fundamentally separated from one another. What is more, these separated individuals come to the world as persons who, to that extent, are not needful of other individuals for being what they are: persons. Of course, they live in communities and their social living is made up of relations among individuals that are no different from those that mark communalist societies. The critical difference is that whereas in the latter those relations are adjudged necessary, in modern individualism, they are considered contingent, products of negotiations—hence, the dominance of the idea of contract—among and between individuals. The underlying assumption here is that even though individuals may and do cooperate with one another, such cooperation is not essential to their personhood in both its constitution and its action in the world. Certainly, the individual needs others. But it satisfies this need based on its calculation of its interests and how best to attain or advance them. This is a fundamental difference between modernity-inflected individualism and other types of individualism.

There is an irony here that deserves some airing. Precisely because there is no entitlement in the relationship that individuals have with one another in an individualist setting, each knows that she must cultivate the other if they are going to have a mutually rewarding relationship. The upshot is that the problem of free riding is pushed to the surface and seriously and continually addressed in both theory and practice. In theory at least, each always considers the impact of his actions on his fellows. Of course, we have enough incidence of self-preferential behaviour in such societies. The difference is that no one thinks that another owes her anything that is not a product of their mutual consideration of what such behaviour will add to their respective self-interests.

In communalist society, on the other hand, as individuals, we take one another for granted. Because many of us have been socialised into thinking that individuals don’t matter or, when they do, this must not be openly acknowledged or solicited, we end up not cultivating one another as we should. Family members think that their successful members owe them something for the sheer fact of their being members of the same family. Damn the family member who withholds help to another member on account of the latter not having earned the former’s consideration in the sharing of his fortune. We take advantage of each other, and we dare not complain when we are victims!

It is not only in its account of the nature of the relationships between and among individuals, and those between individuals and the groups to which they belong or in which they participate, that this individualism differs from its other versions. The individual who is not organically connected to any other is for this reason adjudged free. In fact, it is a basic claim that the modern individual is a free being whose nature is typified by freedom. He is free to be whatever he wishes to be as long as he does not in the process impair the ability of others to similarly display or exercise their freedom. This means that we may not force another to our point of view, even when, especially when, it is within our power to do so whether as individuals or as groups. That is, we are enjoined to let the individual be—in all his utter difference from or with what we might prefer as an identity, a way of life, and so on. This emanates from that attribute of the modern individual that is at the core of that philosophical orientation: autonomy.

Thanks to this attribute, we are disabled from telling the individual how to lead her life, what to do with it, even when it is obvious that the choices being made by the individual concerned are unlikely to enhance her welfare. Yes, we may counsel and remonstrate with her, do our best to persuade her that her choices are injurious to her interests as we understand them from relating with her. But she is the ultimate judge of what to do with our advice; whether or not to accept it. We must never deign to be the best judge of what is good for any individual other than ourselves. We shall be examining momentarily some implications of what we have so far described as the individualist mode of social living.

We do not respect individuals because we love their choices or agree with them or even find them agreeable in the least. Indeed, we are required to respect them more so when we hate their choices and are repulsed by who they are or what they do. Respecting t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface to the U.S. Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- One Why Africa Must Get on Board the Modernity Express

- Two The Sticky Problem of Individualism

- Three The Knowledge Society and Its Rewards

- Four Count, Measure, and Count Again

- Five Process, Not Outcome: Why Trusting Your Leader, Godfather, Ethnic Group, or Chief May Not Best Secure Your Advantage

- Six Against the Philosophy of Limits: Installing a Culture of Hope

- Index