- 318 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

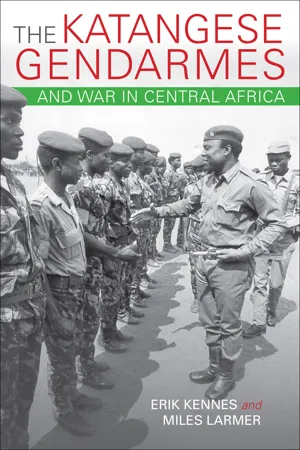

The Katangese Gendarmes and War in Central Africa

About this book

A history of the 1960s unrecognized state's army and their role in Central Africa's political and military conflicts.

Erik Kennes and Miles Larmer provide a history of the Katangese gendarmes and their largely undocumented role in many of the most important political and military conflicts in Central Africa. Katanga, located in today's Democratic Republic of Congo, seceded in 1960 as Congo achieved independence, and the gendarmes fought as the unrecognized state's army during the Congo crisis. Kennes and Larmer explain how the ex-gendarmes, then exiled in Angola, struggled to maintain their national identity and return "home." They take readers through the complex history of the Katangese and their engagement in regional conflicts and Africa's Cold War. Kennes and Larmer show how the paths not taken at Africa's independence persist in contemporary political and military movements and bring new understandings to the challenges that personal and collective identities pose to the relationship between African nation-states and their citizens and subjects.

"A fascinating story which is tied to the colonial development of Katanga province, cold war politics in Central Africa, the crisis of the postcolonial state in the Congo, and the interregional politics in the Great Lakes area." —Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja, University of North Carolina

"A major contribution to our understanding of postcolonial politics in Africa more broadly and sheds light on the survival of militias over time and forms of subnationalism emerging from regional consciousness." —M. Crawford Young, University of Wisconsin, Madison

Erik Kennes and Miles Larmer provide a history of the Katangese gendarmes and their largely undocumented role in many of the most important political and military conflicts in Central Africa. Katanga, located in today's Democratic Republic of Congo, seceded in 1960 as Congo achieved independence, and the gendarmes fought as the unrecognized state's army during the Congo crisis. Kennes and Larmer explain how the ex-gendarmes, then exiled in Angola, struggled to maintain their national identity and return "home." They take readers through the complex history of the Katangese and their engagement in regional conflicts and Africa's Cold War. Kennes and Larmer show how the paths not taken at Africa's independence persist in contemporary political and military movements and bring new understandings to the challenges that personal and collective identities pose to the relationship between African nation-states and their citizens and subjects.

"A fascinating story which is tied to the colonial development of Katanga province, cold war politics in Central Africa, the crisis of the postcolonial state in the Congo, and the interregional politics in the Great Lakes area." —Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja, University of North Carolina

"A major contribution to our understanding of postcolonial politics in Africa more broadly and sheds light on the survival of militias over time and forms of subnationalism emerging from regional consciousness." —M. Crawford Young, University of Wisconsin, Madison

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Katangese Gendarmes and War in Central Africa by Erik Kennes,Miles Larmer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & African History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1Becoming Katanga

THIS CHAPTER, IN establishing the history of the area of central Africa that became Katanga, simultaneously and intentionally echoes and challenges the proto-national narratives underlying the creation of nation-states in Africa in the mid-twentieth century.1 Historians and African leaders sought at that time to retrospectively construct the history of their disparate new territories in order to project a coherent self-conscious national narrative, to encourage national integration, and to discourage alternative and/or competing forms of affiliation.2 There is a well-established literature stressing the “imaginary” or “invented” nature of nation-states generally.3 The particular artificiality of African nation-states, constructed largely along the lines drawn by colonists in the wake of the scramble for Africa of the 1880s and 1890s, is equally well known: the process of nationalist imagining in late-colonial Africa was particularly brief; involved a relatively narrow elite, many of whom were Europeans; and allowed little substantive debate over the composition, character, and culture of the new nation-state.

If this general framework applies to (post)colonial Africa as a whole, then it can be witnessed in its most extreme form in the Belgian Congo and its independent successor. Various factors contributed to the extremely late and partial affiliation of most Congolese people to anything approximating a unified nation-state: the nature of colonial administration, which made no substantive effort to project any form of proto-national identity; the related lack of political reform and establishment of “modern” forms of representative institutions until the rushed decolonization of the late 1950s; the very basic level of mass education provided by the colonial state; and infrastructural development that enabled the export of raw materials but did little to integrate the territory within Congo’s borders. As will be illustrated below, these and other factors contributed to the emergence in the 1950s of African political expression that was, with few exceptions, primarily ethnoregional in nature. The outright ban on territory-wide political parties maintained until the elections of December 1957 meant that ethnoregional cultural associations provided the main basis for anticolonial political expression and the majority of Congo’s political parties in the rapid decolonization process of the late 1950s. This contributed significantly to the forms of political conflict that developed in the run-up to, as well as during and after, independence in June 1960.

In the territory that would become Katanga, there was an equally limited sense of proto-national consciousness, but it was at least as coherent a basis for an imaginable nation-state as the far larger and more disparate Congolese state of which it was a part. This is, then, the precolonial and colonial history of the nation-state of Katanga, a counterfactual history that describes the foundations of the ultimately aborted project of Katangese statehood which, in many ways, closely resembles the parallel projects of nation-making that unfolded simultaneously across postcolonial Africa at this time. This is not to deny that the Katangese nation-state initiative necessitated the artificial projection of unity and belonging onto a highly uneven—geographically, economically, and culturally—territory, the reification of some characteristics of some of its peoples as the dominant features of national identity, and the marginalization or silencing of others. “Katanga” was an elite-dominated project, articulated and instituted by conservative political leaders, chiefly authorities and their European economic and military partners. While the anticommunist orientation of the Katangese political project was distinctive in African terms, it was far from being the only Western-oriented, elite-dominated, or ethnically partial nationalist project in Africa.

The importance of this history is twofold. First, both the precolonial and colonial history of Katanga and Congo shaped these societies in ways that created a strong propensity toward autonomy and even secession among Katangese elites. Second, the reconstructed historical memory of precolonial Katanga, opportunistically asserted with the sudden and largely unanticipated arrival of urban political association and the prospect of self-rule in the late 1950s, was, together with elements directly borrowed from colonial statehood, central to the articulation of a “national” Katanga in the run-up to and during the secession itself. One of the challenges of such an analysis is to distinguish between these two forms of history, that is, the “actual” effect of historical factors on economic, political, or societal change, and the asserted use of history in its memorial and mythical forms. It is suggested that, while the political culture of self-styled “indigenous” Katangese leaders required a highly imaginative interpretation of Katangese history (for example, in its assertion of the so-called Lunda Empire), the political economy of Katanga (particularly the relationship between the territory and its mineral wealth—mining companies almost literally made the state structures in Katanga—made it possible to practically envisage an independent Katanga, created the conditions for hostility toward Kasaian labor migration, and yet placed identifiable limits on the ultimate success of the secessionist project. While Katanga’s alliance with Belgian advisers and capital had the effect of preserving Katanga’s comparatively developed infrastructure development—and, ironically, making possible subsequent Zairianization measures—the practical impact of colonialism on Katanga made it impossible to effectively integrate the territory’s diverse population into a cohesive national project.

“Katanga” before the Congo Free State

The social and political formations present in the area of central Africa that ultimately formed Katanga had for centuries been significantly shaped by their trade-based interactions with the wider world. Metalworking, in iron but also in copper, was central to the growing economies of the region. The area around Lake Kisale was an important center for metalworking, and its prosperous inhabitants produced a food surplus, including dried fish, which they traded for, among other goods, copper mined to the south in the modern Copperbelt. In the fourteenth century a centralized kingdom, under the Kongolo dynasty, developed among a people known as the Luba. The origins of the Luba political aristocracy can be traced back to three clans: one Songye, one Kanyoka, and one Lunda. The oral tradition clearly refers to a link between the Lunda and the Luba: around 1400, the female ruler of the Lunda, the Lueji/Ruej, married Tshibinda Ilunga/Cibind Irung, a member of the Luba aristocracy. Luba political principles were incorporated into the Lunda political system, thereby creating an element of unity between what was later southern and northern Katanga.4

Several waves of westerly out-migration from the core Luba area (located, according to oral tradition, in a place called Nsanga a Lubangu) took place during the early stages of Luba consolidation, commonly associated with intra-aristocratic conflict and the need to address population concentration at a time of famine, probably around the fifteenth century. This led to the distinction between the Luba Katanga (or Lubakat, also known as Luba Shankadi, probably meaning “faithful”) and the Luba Lubilanji in Kasai, a distinction which became increasingly rigid in the subsequent period and which has direct relevance for this history.5

The Lunda kingdom meanwhile developed in the vicinity of the upper Kasai River. A Lunda dynasty developed, the king of which became known as the Mwaant Yav, with his capital at Musuumb/Musumba, near to Kapanga territory. The Lunda political system allowed for integration of non-Lunda communities, while granting them significant autonomy. Local communities retained authority over the land and the people living on it. Integration of autonomous territories was, however, assured through the cilool (kilolo), or tax collector, and the yikeezy, or inspector, who preserved political and economic ties with the central Lunda polity. The Mwaant Yav was lord of all land (ngaand) as well as the supreme tax collector. A second integrative element was the assertion of nonbiological kinship between the Lunda and non-Lunda groups, creating a meaningful fiction that the successor to any title of authority, whether related to them or not, was identified with the original titleholder.6 Affiliation to this system was attractive not only for economic reasons but also for the authority gained via association with the prestigious kingdom: this partly explains the willingness of non-Luba peoples to recognize the authority of and pledge allegiance to Tshombe during the secession.

The Lunda system’s capacity to absorb neighboring polities under its federal umbrella without requiring their political reconstitution was, Vansina argued, central to its success.7 In particular, the adoption by the Lunda of Luba political principles not only enabled successful incorporation: it was later suggested that this made for a degree of precolonial unity in what later became “Katangese” territory.8 Bustin, however, concludes that, although its federal nature aided its successful growth and expansion, the resultant factionalism that arose over succession to the Mwaant Yav title also prevented the Lunda kingdom becoming a more stable state-like system.9

Nevertheless, during the seventeenth century the Lunda kingdom grew to become one of the dominant political forces in central Africa. The Lunda developed trading links with the Portuguese in Angola and trade routes to the Atlantic coast which connected them with global trade and, among other benefits, enabled the import of American crops such as cassava and maize.10 Cassava in particular enabled food surpluses to be produced, leading to population growth and an expansion in the land under harvest. Tribute payments, often in the form of ivory, were redirected to the western trade routes, with guns and other manufactured goods being imported; slaves also became a major export. The possession of firearms strengthened the Mwaant Yav’s authority and the kingdom’s capacity for slave raiding. Backed by this increasingly powerful central authority, Lunda tribute collectors established new states in the seventeenth century, subordinating and taxing the existing inhabitants, particularly in areas producing attractive goods, such as in the Copperbelt area to the south and east. The most important of these was the Lunda Kazembe in the Luapula valley, which by the end of the eighteenth century had become a major trading center in its own right, linking the Lunda to Indian Ocean trade routes. The Kasanje kingdom, established on the upper Kwango River in modern Angola by Lunda leaders, enjoyed successful trading relations with both the Lunda and the Portuguese.11 Through these links, the Lunda traded and established relations with coastal societies such as the Bakongo, with whom they would subsequently be integrated into the colonial state of Congo. While this familiarity should not be conflated as constituting a meaningful building block for the emergence of a proto-national identity, Lunda and Bakongo shared a federalist tendency that in the late colonial period reasserted itself in the parallel approaches of the Alliance des Bakongo (ABAKO) and the Confédération des Associations Tribales du Katanga (Conakat) to the future Congolese state.

Long-distance trade expanded throughout the nineteenth century, but as the West African route declined in importance in relation to its East African equivalent (where slave exports had not been effectively outlawed), established central African powers were destabilized by the activities of societies of armed raiders with their origins in or linked to creole Swahili coastal societies, such as the Nyamwezi. Msiri, one such Nyamwezi trader, was able in the 1880s to extend his control over a large part of Luba and Lunda territories between the Lualaba and Luapula Rivers and to establish a fully fledged state in this area.12 A small BaYeke core population established a wider polity via the appointment of local chiefs and, crucially, intermarriage with societies indigenous to the territory that would become Katanga.13 The newly established BaYeke conquest state of Garenganze flourished until the 1890s, trading in copper and ivory and defending its position by force of arms. In comparison, the Lunda kingdom drastically declined, primarily because of the success of its former subject peoples, the Tshokwe, in disrupting and taking over its Atlantic trading routes through military means in the third quarter of the nineteenth century.14 Lunda chiefs in what would soon become the colonies of Angola and Northern Rhodesia nevertheless retained their fealty to the Mwaant Yav. Memory of this powerful kingdom would, as we shall see, cast a long shadow over the subsequent political history of the region. Similarly, historical conflict between the Bayeke and the Baluba, and the animosity between the Lunda and Tshokwe, would be reconstructed in late-colonial and postcolonial political conflict: as Lemarchand observed in 1964, “memories of past onslaughts tend to fuse with recent experience, thereby intensifying contemporary political cleavages.”15

The Colonial Takeover

The diverse responses to the colonial invasion of what would become Katanga were shaped by African societies’ preexisting relationships to the region’s peoples, resources, and trading links. Lunda royalty, having been defeated and driven out of their capital by the Tshokwe in 1888, had effectively collapsed and consequently did not offer a meaningful response to colonization.16 The smaller but militarily more powerful BaYeke state was somewhat better placed to respond, but it too had been weakened by the 1891 rebellion by the Sanga, one of the indigenous subject peoples under the yoke of Msiri’s autocratic rule. It was precisely the mineral resources controlled by the BaYeke (together with persistent rumors about vast gold deposits) that attracted Belgian and British agents to this area in the late nineteenth century.17 The British South Africa Company (BSAC), established by royal charter in 1889, was frustrated in its efforts to claim Katanga for Britain via a treaty with the Msiri by some skillful reinterpretation by King Leopold of the concession he had been granted by the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885. The founding of the BSAC had provided a stimulus to Belgian surveying of mineral wealth, and the 1889–1891 period witnessed intense competition between British and Belgian agents before the Free State was able to claim Msiri’s capital. Copper mining had been carried out in this region since the fifth...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Becoming Katanga

- 2 The Katangese Secession, 1960–1963

- 3 Into Exile and Back, 1963–1967

- 4 With the Portuguese, 1967–1974

- 5 The Katangese Gendarmes in the Angolan Civil War, 1974–1976

- 6 The Shaba Wars

- 7 Disarmament and Division, 1979–1996

- 8 The Overthrow of Mobutu and After, 1996–2015

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index