![]()

PART ONE

Getting Started

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Why Negotiation Matters

People negotiate all the time. We just don’t always realise that we could be doing it, should be doing it, that we are doing it, or indeed how to do it well.

From the renegotiating of terms with a new client to the difficult conversation about missed performance targets with a supplier; from the request to your boss to have your role re-evaluated to the demanding of a lower monthly fee from your broadband provider, almost every interaction in which we are requesting something from someone else is a negotiation.

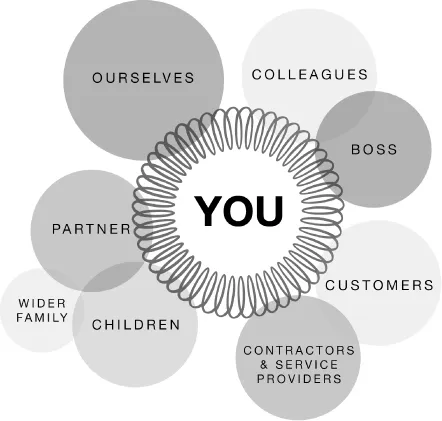

Some negotiations in life are more obvious than others. When my team works with delegates in our workshops, we will always ask them to imagine all the people they might negotiate with over the course of a day, week, month or year.

Let’s start with the most obvious people who come to mind when you think of ‘negotiation’ – the people you work with most closely. What kinds of negotiation might you engage in with them?

Colleagues: Who delivers the difficult message to the boss? Who does what work, gets what desk or pays for the coffee?

Boss: You’re likely to negotiate on a number of issues, from salary to promotion, job title, who’s on your project team, time off and deadlines.

Suppliers, customers, partners or clients: You might negotiate about price, risk, volume, deadline, guarantees and performance indicators. These are what I would call ‘obvious negotiations’; you may even note them in your diary as ‘2pm negotiation with client’.

But we negotiate in our personal lives too …

Salespeople, estate agents and service providers: Outside of work you are likely to engage in negotiations with the suppliers of services or products to you or your family. Examples might include deliberations over the sale price of a new dining table with the furniture store salesperson, trying to agree a speedier completion date for a house sale with your real estate agent or seeking a lower tariff with your energy supplier in exchange for not moving to one of their competitors. Interestingly, many people wouldn’t view buying furniture as an opportunity to negotiate, they would just pay the price on the ticket, whereas others will take great delight in trying to secure a discount, no matter how small. Similarly, some people will never really question the tariffs set by their energy companies and will simply sign up without really considering what could be changed or improved in the standard package.

Of course, a competitive and heavily populated market for energy supply should provide all of us with the incentive to push back and negotiate for better terms. Quite simply, if a provider says ‘no’, it is now easier than ever for us as consumers to find someone else who can provide what we are looking for. Similarly, I once ran a training programme at which one of the attendees was a sales director for a well-known high street furniture retailer. She explained that if a customer ever paid the ticket price for a product at their stores, the salespeople would think they were a fool. Why? Because the sales-people were mandated to offer an immediate 10 per cent discount if asked for one. If the customer demanded more, they would then ‘reluctantly’ go to 12.5 per cent. If the customer still wanted more, they could speak to the manager who in most cases would ‘reluctantly’ offer a further 5 per cent. In short, the discounts are often there to be had and are factored into the list price; you just have to ask for them.

Partner: On an almost daily basis you will have cause to negotiate with your husband, wife, girlfriend or boyfriend. This might be in relation to holiday plans, child-care arrangements, financial contributions or who will do the washing up.

So, I start most mornings (particularly on very cold, wet and windy days) by turning to my husband and saying: ‘If you walk the dog, I’ll get Leo ready for nursery.’ (Leo is my toddler; you’ll hear more about him in a moment.)

What’s important about the proposal I’ve made to my husband? It’s a trade. Why does the fact it’s a trade matter? Well, quite frankly, it’s because I don’t want my husband thinking I’m going to do everything for him. He has to do something in return. The interesting thing is that we often readily trade based on ‘If you …, then I …’ with friends and family. The problem is that we don’t tend to carry that through to our professional lives. Later on in this book, I’ll tell you why that is one of the biggest mistakes we can make at the negotiation table.1

Wider family: We also have to negotiate with wider family members, such as our parents, siblings and extended family over issues such as allowance, curfews, family celebrations and which distant relatives you have to invite to your wedding.

Around August every year I will also start the annual negotiations with my mother-in-law about where we are spending Christmas that year. (This has become much more challenging since our son arrived in the position of first grandchild!) This leads us nicely on to the most effective negotiators.

Children: Those of you who have spent any substantial amount of time around young children will know that they are master negotiators.

I told you I would come back to my toddler … He is an amazing negotiator. Not because I have taught him, but because children just are. The reason for this is because they focus all of their efforts on achieving the desired result (be that second helpings of ice cream, a new toy, watching one more episode of a cartoon, staying up late …), and they will do pretty much anything it takes to get that result.

My team have trained negotiators in big companies around the world, and one of the things that we are frequently told by nervous negotiators is that they are scared of ‘pushing too hard’ when they negotiate in case people don’t like them. Whereas, the interesting thing about children as negotiators is that, up until about the age of seven or eight, they don’t really care that much about what people might think of them. It’s only when we approach our teens that we start to become more self-aware and concerned as to how we might be perceived by others. So, until that happens, children will focus purely on getting the result that they need to ‘succeed’. For my son, this includes stamping his feet, throwing things on the floor and screaming; because of this it’s not uncommon for him to succeed in getting what he wants, particularly if we’re in a busy public place!

Now of course, the advice here is not to stamp your feet and scream every time you get to the negotiation table. I’m not convinced that is going to help you bag that promotion or salary increase. But what we can learn from children is that sometimes we should think more about what we need to do to get the result, rather than dwelling too much on what people might think about us. I am not advocating that you shouldn’t care at all about whether people like or loathe you; as you will see in Chapter Five, this can have an impact on the outcome of your negotiations. But it shouldn’t be the only thing you are concerned about. You still need to have the right facts and information at your fingertips, the ability to stand firm, and almost certainly the confidence to say ‘no’ in order to get the right result. In short, you need to get the balance right.

We might be familiar or experienced in negotiating with all of these groups, but we haven’t yet looked at the most challenging of negotiators, the one we have to face alongside every other counterparty.

Ourselves: Ladies and gentlemen, I would like to introduce you to the little voice in your head. The little voice in your head is the forgotten party in many negotiations, and yet it has the ability to derail the most prepared and intelligent of people. It can make you sell yourself short, lose your confidence or assume you are in a far weaker position than you really are.

It’s easy to recognise that little voice. It often sounds something like:

‘Don’t ask for that, it sounds greedy.’

‘You can’t go that high.’

‘You don’t really know what you are talking about do you?’

‘They will never agree to that.’

I routinely work with clients who are smart, intelligent people, who have studied the facts, numbers and details, and who have a plan for how they want to negotiate; yet as soon as they get to the negotiating table that little voice kicks in and preys on their stress and anxiety. And it’s amazing how regularly people are swayed by it. They hear it and panic; then they ask for less, offer more or don’t bother asking at all.

We all have that little voice in our heads. Whether you are young or old, male or female, recent graduate or CEO. It’s there. It’s just that the voice speaks so loudly to some people that it clouds their judgement, erodes their confidence and ultimately prevents them from negotiating as effectively as they could.

How do you stop yourself from being a victim of the little voice in your head?

1. Get to know your little voice. One of the most powerful ways to combat that little voice is simply to recognise it’s there! By accepting and recognising its existence, you have already taken away some of its hold over you, as it is then less likely to be able to pop up and derail you unexpectedly.

2. Listen to it. Try listening to what the little voice is saying. Reflect on the messages you hear in your head when you are in a high-stakes or stressful negotiation. Annoying and limiting as that little voice is, it also reflects your inner concerns, apprehensions and fears. By simply writing down what that little voice says to you at high-pressure moments, you can prepare to fight back next time.

3. Counter it. Once you have identified the negative messages, you can start to build robust responses. If in preparing for a salary negotiation that little voice whispers, ‘They will never agree to that figure’, or, ‘You’re not worth that much’, use this insight to your advantage by researching why you are worth that much or what other employers are paying for your level of expertise. We are most vulnerable when we haven’t prepared or don’t have supporting information, so listen to the fears being voiced in your head, and then go and find out all the information you need to answer back.

4. Drown it out. So much of effective negotiation is about confidence. Negotiation can be challenging, awkward and uncomfortable, and this impacts our performance. One tip is to start to drown out the negative messages before you even get to the negotiation table. Before that little voice is able to kick in, take the time to tell yourself what you really want to hear: that you are valuable, worth it, well prepared, confident, compelling … and keep telling yourself that.

5. Recognise they have one too. Guess what? It’s not just you who has the little voice. Your counterparty does too. And their little voice is whispering to them about their pressures and anxieties. A smart negotiator realises that if all they focus on is their own little voice then they are missing a huge opportunity to tip the balance of power and gain valuable insight as to the key issues in the negotiation. While doing your research, take the time to think about what the concerns and fears of your counterparty might be. By understanding those, you can use the information to your advantage. Check out the next chapter to find out more about this.

This gives you some insight into just some of the negotiations that happen in our lives. We’ll get into the details of how to negotiate with each of these counterparties later. First, let’s demystify the idea of negotiation itself.

When my team are training businesspeople on how to negotiate, we use the following definition:

‘Negotiation is two or more parties discussing differences in order to try to reach an agreement.’

We use this definition because it is broad and not too prescriptive.

First, notice that the definition does not mention money. There is no reference to pounds, euros, dollars or yen. We do this very deliberately because we don’t want you to think that the only negotiations that matter are the ones relating to cost, fee or price. Not everyone will negotiate on financial matters all the time. Indeed, some people may never negotiate on those things. Some people might negotiate on risk, deadlines, volume, policies, positions, points of view, politics or location, and they just won’t be exposed to financial negotiations. These negotiations are no less important or influential in our lives. We should not be dismissive of negotiations just because they don’t contain discussions on mega-bucks.

Secondly, this definition does not present boundaries as to what negotiation might look like. There is no one ‘type’ of negotiation, just as there is no one type of counterparty. We negotiate a great number of different things and as a result our negotiations can ‘look’ very different. A negotiation could look like you and me having a conversation over a coffee. Or it could look like a multi-party, multi-variable, cross-jurisdiction, politically sensitive, disputed contract renegotiation. And everything in between.

Thirdly, this definition of negotiation makes reference to the fact that you might not reach agreement. Not all negotiations end in a handshake or a signature. Some negotiations will end in deadlock, dispute or a very pleasant acceptance of the fact that the numbers just don’t add up on this occasion.

So, we begin this book by being clear that negotiation is a fundamental part of what it is to be human. It’s the skill that is going to allow us to get what we want, need or deserve because, despite the old saying, good things don’t always come to those who just wait … and wait … and wait. You need to take the initiative, be in control and ask.

What’s the problem?

Despite the fact that we negotiate every day, the reality...