![]()

1

ART

The expressionists’ initial battle cries ring out: Impressionism conveys photographic realism, tinged with sentimentality (in varying degrees of delicacy), and decorated with appeal (in varying degrees of talent). Precisely this represents a decline into conventionality. The world of the practical man is a characterless means of communication: between the natural object and the art object there exists an unbridgeable vacuum.

For the artist, everyday reality is coincidental. The natural object is created anew in the realm of art, without obligation to its original form. Similarity, when viewed in this light, is an extra-artistic term. Henri Matisse, in his 1908 “Notes of a Painter”, strove to interpret the intellectual process thus: “From the standpoint of subjectivity, we have seen the thought, or nature as viewed through temperament, replaced by the theory of the equivalent or the symbol. We formulate the rule that the sensibilities and conditions of the soul, which are called forth by a certain process, impart signs or graphic equivalents to the artist, by which he is able to reproduce the sensibilities and conditions of the soul, without the necessity of providing a copy of the actual spectacle”.

No copy of the actual spectacle. Thereon lies the emphasis. The artist takes in nondescript data, which he allows to take shape through his creative activity. Expressionism does not represent the object’s tangible reality: it is concerned with a fundamentally different plane of existence. The artistic world is pushed back into the consciousness of the artist, who then articulates his subjectivity with an absoluteness that wrests all subject matter from it – that renders it empty. But it is the distinguishing characteristic of art that that which is most personal to the artist must be strictly objective – otherwise his art is false. Purely aesthetic conditions determine whether a seemingly straight line changes course when an artist is creating a photograph, or whether a group of words or series of sounds is antithetical to regular speech.

The important thing is to recognize that we are dealing with the artist’s necessary state of being. If this condition is lacking, we are left with an empty formalism that cannot get beyond anemic, decorative attractions.

LITERATURE

As we consider Expressionism’s impact on literature, it will become apparent to what extent Expressionism is a general state of mind, rather than a special case in the visual arts.

Many have smiled at the broken syntax of modern poets. August Stramm, who died in the war, published verses in which isolated, melodious, strongly meaningful words supported the lyrical texture: they were labeled the ravings of a lunatic. [Carl] Sternheim’s pronoun-free, newly-constructed dramatic phrases, and Georg Kaiser’s bold word architecture have been regarded as talented “aestheticism” at best.

But the recognition that spoken expression in art takes place on another level than that of communication through words as they are commonly spoken – that a completely new complex of laws and possibilities comes alive – has indeed become accepted by the general public. Georg Kaiser’s From Morn to Midnight stands henceforth as the representative work of an era. What was once considered absurdist diction has now been legitimized as an artistic constraint. Kaiser portrays a man’s attempt to leap from a dull bank cashier’s existence to the big wide world. He ends with a revolver shot. So that we may be made keenly aware of the novelty of this, let us consider how an embezzler’s suicide would have transpired in an impressionist drama. It would take place in some quiet corner and involve ironic or accusatory self-mutilation; a face would be turned up toward heaven, with one eye on Browning. Georg Kaiser’s cashier, however, stands in the Salvation Army Hall of Repentance, left hand …

Cashier

(Feeling with his left hand in his breast pocket, grasps with his right a trumpet, and blows a fanfare toward the lamp):

Ah! – Discovered. Scorned in the snow this morning – welcomed now in the tangled wires. I salute you. (Trumpet.) The road is behind me. Panting, I climb the steep curves that lead upward. My forces are spent. I’ve spared myself nothing. I’ve made the path hard where it might have been easy. This morning in the snow when we met, you and I, you should have been more pressing in your invitation. One spark of enlightenment would have helped me and spared me all trouble. It doesn’t take much of a brain to see that – Why did I hesitate? Why take the road? Whither am I bound? From first to last you sit there, naked bone. From morn to midnight, I rage in a circle … and now your beckoning finger points the way … whither? (He shoots the answer into his breast, the trumpet blast fading out on his lips) [English translation by Ashley Dukes. New York: Brentano’s Publishers 1922].

This excerpt from a thoroughly formalized world would be a caricature if integrated into our everyday reality. The drama’s concept, meaning and locution make up a unique world which, when compared with reality, seems no less contorted and arbitrary than an expressionist landscape. This man, who turns his face toward the lamp, parodying his readiness for death with a grotesque musical instrument, who lets the stages of his life roll over him in fragments, accentuating them with abrupt trumpet blasts, would be incomprehensible, even laughable, in a world arranged psychologically. But the structure of this work organizes his loops, reductions, and fragmentations into a prepared mental visual space: and thus this atonal sally to the great god of the Salvation Army is portrayed no less logically than that moody suicide in the Impressionist scenery.

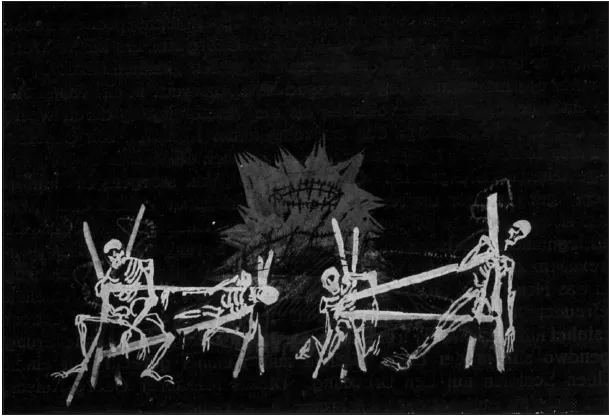

Figure 3. [Robert Neppach,] design for Ernst Toller’s play Transfiguration.

Kaiser’s work stands at a crossroads. From a distance, it seems to deal with the struggle between the two generations; introspection and structured life fight their final duel, sparks flying. If the expressionist speech structure falls short of clear realization, this can be traced back to the attitude of direct speech in drama, which tries to distance itself from formative principle, aligning itself to the very end with the natural object. Intellectual attitude in poetry is completely transparent, since it essentially stands outside of contact with reality as we know it, attempting to be nothing more than a literary creation. Kasimir Edschmid, the most adept expressionist in Germany, describes the attitude of the expressionist artist in a popular tone. “He doesn’t see, he looks. He doesn’t describe, he experiences. He doesn’t reproduce, he creates. He doesn’t take, he seeks. The chain of facts no longer exists: factories, houses, sickness, whores, screaming and hunger. Now we have visions of those things. Facts have a meaning only insofar as the hand of the artist reaches through them to grasp for what stands behind him.” Though these words are quite generic, they do capture the tone of the sentiment. The fundamental disinterestedness between natural object and art object must be expressed in expressionist poetry – if there is even any other kind. Johannes R. Becher creates a “Japanese General”:

A visage broad spattered in bright day

Where among lotuses bobbing barges turn.

The zigzag eyes (… of a highly ranked

Decaying pit …) swell osseous spumes.

As though hollowed out by cartridges.

The formal elements do not grow out of psychological appeals, emotional memories, or vague experiences, but get their meaning and order from a precise, stylistic concept. There is no question of a portrait in the conventional sense of the word. A parallel to the pictorial approach is immediately evident: this poetry likewise attempts to construct the great, definitive moments of the subject’s existence – whether of an intellectual or a physical nature. Slaughter, decay, battle, escape and rescue have grown into a composition in and through this face. This is not the amorphous simultaneity of futurism, which, concerned only with synchronicity, paints birth, marriage and death in one, hoping thereby to comfortably achieve a creative form. Becher’s verse, on the contrary, thrives on its austerity of form. Perhaps it does not bear it effortlessly, but it willingly accepts it as its highest principle. It may easily be said that in this poem, the connecting links have simply been left off. It is only through the impact of its intrinsic attributes that a nondescript feeling is created, which hovers between the memory of a brightly-coloured Japanese woodcut and the typical life of a general. But the concept is not nondescript: it is created very precisely. The construction of the dynamic figure, with its reserve of vital motion, of life force, is not the result of sentimental dreams, but rather of an admittedly poetic understanding of proportion and accentuation. But here we can only verify this completeness of form, not explore it in depth. The sole purpose of the natural object is to act as an initiator. The beginning of a poem by Gottfried Benn will demonstrate how a portrait becomes visible, based on elements that are in principle foreign to the natural object:

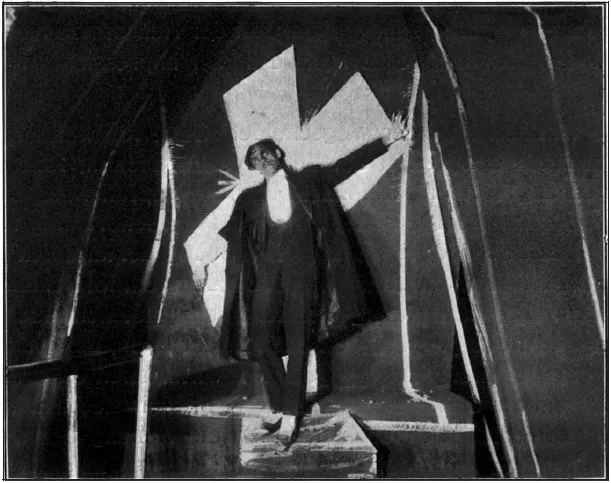

Figure 4. [Karlheinz Martin,] From Morn to Midnight (Ilag-Film).

To a Danish Girl

Herms or Charon’s Ferry

or maybe a Daimler in flight

what from the stars’ assembly

breathed you in deep delight,

a grove was your mother’s playground,

with the south, thalassa, she grew

and alone bore you spellbound,

you, the Nordic dew –

[Translation by David Paisey. Manchester: Carcanet 2013]

What is here a means of composition is drawn from poetic consciousness itself. Temporal development, spatial depth, the heroic element of fate and the splendour of existence take shape, based not on the dimensions of the natural object, but on a concept of aesthetic awareness. It is the artist who speaks, and only the artist. It is not the world of business, it is not the world of everyday pleasantries, it is not the world of family celebrations. This kind of reality is simultaneously highly ambiguous and highly explicit. If one acknowledges the poetic world, it unfolds with compelling clarity. If one rejects it, what remains is a phantom, an echo, a word, a grimace.

The difficulty lies primarily with the belief in psychology. The highly questionable hypothesis that people understand each other because similar causes produce similar reactions is arbitrary. Though it serves only the practical purpose of classification, this assumption has secured psychology its primacy. People believe that, without having to change position, they can fit every possible level of the soul into the space of a very limited way of thinking, by means of empathy, by relating, by savouring understanding. They are not conscious of the fact that a leap is required – a nearly impossible leap in fact, into a new dimension. If the artist creates with a metaphysical purpose, his work cannot be perceived as art if he fails to change his position.

This forgoing of psychology, or any sympathy with nuance, is evident with programmatic clarity in an older novel by Carl Einstein: Bebuquin or the Dilettantes of Wonder [1909]. It is a work of very deliberate intellectual architecture, borne by a strong determination to personally construct reality. Its content-related determination may indicate Bebuquin’s avowal to get beyond temporal and spatial continuity, and beyond definitive psychological consistency. “He went into the empty parlour: I don’t want to be a copy, no influence, I want myself, I want some-thing unique from my own soul, something individual, even if it is only holes in the private air. I can’t start anything with things, one thing involves all other things. It stays in flux and the infinity of a point is a horror.” [Translation by Patrick Healy. Dublin: Trashface Books 2008] If the metaphysical location, so to speak, is provided here, then the novel’s composition and mode of expression must be organized appropriately. Psychological empathy is dispensed with; little value is placed on colourful effects. The only important thing is the intellectual architecture, the relationship in space, the conscious direction of the dynamic. From the description comes the construction of reality according to its own laws. A circus scene. “People ignorant of each other traipsed in spoonfuls into the circus, a colossal rotunda of amazement, sat packed together and waited for Miss Euphemia. The ornaments of excited hands ran along the railings, and the globe lamps swung their milk buckets.” The spatial aspect is represented according to its inner tension, with the aim of detaching meaning from the unique. The passive image of impression has become a constructive new creation. The point is not whether “passive image of impression” is a polemic phrase with no counterpart in reality. In this prose, the compositional takes precedence. Structure possessing lopsided rhythmic and dynamic qualities emerges as a programmatic challenge, which may be seen as a contextual characteristic of the attitude. This is the “mind-set” of a new generation preparing to accomplish its historical task.

VISUAL ARTS

The young generation’s battlefield were art exhibits and painters’ ateliers. The charge was sounded against what the great French post-impressionist Paul Signac praised as the strongest quality of his masterly predecessors: “They are becoming the glorious painters of fleeting emotions and cursory impressions”. The painters surrounding Manet were of course not interested in naturalism; they were following their artistic conception. What is important to them is the essence of appearance, and that which renders it unique, transitory, irreproducible. Their pictorial methods become refined so that they might realize this. But during the transformation of that which is seen to be the essence of the appearance, history takes place. The neo-im...