1

Existing Approaches to Change in and beyond the Wine Industry

Wine has inspired a vast literature in the social sciences, particularly in sociology, history, and geography. There is much to be taken from this research. In analyses of recent change, however, most existing publications raise and reflect the deep analytical problems of academics working on this and many other parts of economic life. The following critique of existing literature critically discusses not only the research that specifically concerns wine but also the approaches to economic change that underpin it.

To date, several broad theories of change have been used in analyses of the wine industry. The most basic debate is between approaches that emphasize the agency of wine firms and those that give material structures a determining role. Other schools of thought have developed in order to move beyond this opposition. While they have each contributed to knowledge about what determines economic activity in general and the wine industry in particular, they all have analytical limitations which this book seeks to move beyond.

Agency versus Structure: Economics (Still) in Search of Its Actors

The opposition between agency and structure has been the subject of a great deal of thought in social science (Lizardo 2010). When it is transposed into analyses of economic exchange, it generally takes the form of a cleavage between institutionalist economics and regulationist economics. The former stresses choices, calculations, and the contracts firms enter into, while the second focuses on the accumulation regimes and social hierarchies that (it claims) constrain choices, calculations, and contracts. However, both provide a restricted viewpoint that hinders comprehension of the deep causes and consequences of change.

Institutionalist Economics: Calculation and Contracts

Institutionalist economics is the theoretical lens most frequently used, both in general and for the wine industry. According to the originator of its central concept of “transaction costs,” Oliver Williamson (1975), economic actors are above all opportunists whose self-interested and short-term-oriented behavior generates uncertainty that has costs. These costs encourage actors, often aided by the state, to collectively produce institutional safeguards to protect themselves from attacks from their competitors. In their purest form, these measures create an institutionalized hierarchy that is an alternative to pure markets. Those who subscribe to institutionalist economics contend that hybrids of markets and institutions are what structure economic behavior. More precisely, those who defend this theory argue that economic actors put in place explicit or implicit contracts that they rationally follow in order to protect and enhance their material interests. The assumption here is that actors enter into this contractual environment in full knowledge of its constraints and opportunities, as well as what is in their own best interest.

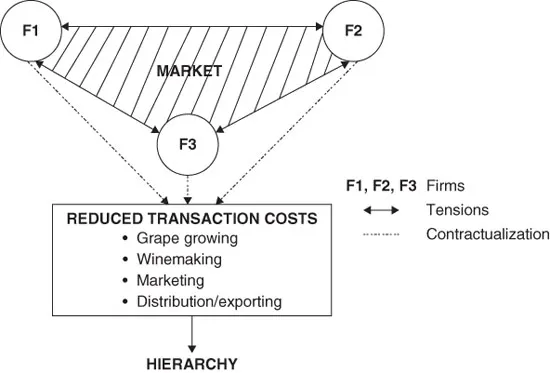

Accordingly, institutionalist economists explain the success of New World wine companies as the result of their high capacity to reduce transaction costs by closely aligning the production of grapes with their processing, marketing, and distribution (see figure 1). For example, they depict straightforward and transparent contractual arrangements between grape growers and large wineries in the United States and Australia as characterized by strict and verifiable growing and processing norms (Rousset and Traversac 2004; Rousset 2005). This set of institutions flows into another set that involves export strategies whereby New World suppliers commit to long-term supply contracts with supermarket chains backed by enforcement mechanisms that reduce transaction costs still further (Traversac 2011). Proponents of this interpretation of the rise of New World wines have a strong tendency to believe that the 2008 reform of the EU’s wine policy was inspired and promoted by European wine companies who saw policy change as a straightforward adjustment measure. The goal was to facilitate change in the hierarchy of the various actors involved in Europe’s wine industry by encouraging the restructuring of grape farming (through the subsidized grubbing out of vines and the end of plantation rights) and introducing new ways of classifying wines (e.g., by reforming product specifications for wines produced in designated areas) (Cafaggi and Iamiceli 2010). Consequently, institutionalist economists see the EU’s new wine policy as simply the result of pressure exerted by the European companies that were best placed to improve their position in this hierarchy, and thus to compete most efficiently with their opposite numbers in the New World (Corsinovi, Begalli, and Gaeta 2013; Gaeta and Corsinovi 2014). This view resonates with an increasingly popular but deeply problematic (Oatley 2011) approach to open-economy politics (Lake 2009) that reduces analysis to making assumptions about the preferences of private actors, mapping how they organize in national settings and only then raising questions about the structuring effects of international institutions.

Notwithstanding the apparent coherence of the theories of economic change of institutionalist economics, they have been hotly contested. The first alternative theory incorporates other institutions that are more distant from economic calculation but are seen as central to the regulation of economic activity.

Regulationist Economics: Accumulation Regimes and Social Hierarchies

Critiques of the overemphasis on calculation in economics abound, but the most sustained of these originated in this discipline itself around the regulationist school of economics. Founded in France by a group of neo-Marxist scholars (Aglietta 1979; Boyer and Saillard 2002), regulationist theory begins from the premise that economic activity takes place in accumulation regimes that structure the relationship between production and consumption, which themselves are reproduced by types of political and social organizations. Consequently, in contrast to institutionalist economists, regulationists claim that extra-economic norms and historically shaped hierarchies are what explain the stabilization of productive and commercial activity at any given period (Goodwin 2009). This approach has been extended by researchers who think in terms of transnational historical materialism, in particular members of the Amsterdam Research Centre for International Political Economy (Overbeek 2000; Van Apeldoorn 2004). These researchers focus on the concepts of control that, they maintain, explain the development and reproduction of capitalism at the global scale. They see these concepts as the mechanisms through which the ideas and practices of the ruling class define the space of possible action for a society. Although for centuries these ideas and practices have been shaped at the national scale, regulationists argue that they have broadened in scope as a transnational ruling class has emerged. Indeed, the latter has come to possess a specific form of class agency that entails operating simultaneously in several national spaces. Regulationists explain this shift as the result of a transformation of the relations between capital and labor and the evolution of different forms of capital (financial or productive).

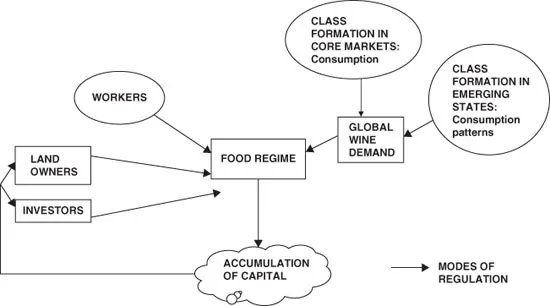

In the context of the study of agri-food industries, the initial aim of research using regulationist economics was to identify food regimes. Using this concept, for example, Harriet Friedman and Philip McMichael identified a mode of relations between farmers and consumers that has stabilized at the global scale as a specific way of accumulating capital. To support this claim, they pointed to a range of materially determinant factors and data, such as modes of imperialist organization, customs tariffs, land rights, and consumption patterns in industrial centers. They explained regime collapses as what happens when a disjunction between these factors precipitates a crisis (Friedman and McMichael 1987).

When applied to wine (see figure 2), variants of regulationist theory postulate that a global industry is shaped by numerous structural factors. Change and stability in that industry is attributed to dynamics caused by “the differing fortunes of consumers, investors, landowners and workers.” Consequently, the task of researchers is to study the “relationship between capital, class formation and accumulation across and within different scales” (Overton and Murray 2013, 703); that is, “the relationship forged between key buyers (and/or owners) in the core country markets and the producers and suppliers in the countries of the global semi-periphery” (Gwynne 2008b, 98–99; see also Goldfrank, Korzeniewicz, and Korzeniewicz 1995). Regulationists thus see relations between growers and wineries as crucial to the external positioning of products in the “global wine consumption space” (Pritchard 2002, 187). Authors who develop and promote such interpretations highlight increases in the global demand for wine and shifts within that demand (Anderson, Norman, and Wittwer 2003, 2004). Their research often seeks to identify change in consumption habits in states where historically high quantities predominated (e.g., France). They generally attribute such change to exogenous shifts in social hierarchies and ways of life. But such research also closely examines new markets for wine, in particular those linked to the development of a middle class in emerging states such as China (Banks and Overton 2010; Parcero and Villanueva 2011; Overton, Murray, and Banks 2012). The overall conclusion regulationists draw is that companies based in the New World have taken advantage of globalization by adjusting their strategies appropriately. In so doing they have deepened a position of comparative advantage based on the availability of suitable land and technologies that enables them to produce wine of standardized qualities while reducing production costs (Campbell and Guibert 2006; Campbell 2007; Cox and Bridwell 2007; Gwynne 2008a, 95), thereby benefiting mechanically from upscaling (Gwynne 2006; Gwynne 2008b; Overton and Murray 2013). From this angle, regulationists see the reform of the EU’s wine policy as simply an adaptation of European production and processing to a regime change that had already occurred in the global economy of wine (Meloni and Swinnen 2012).

Notwithstanding the commitment by regulationists to analyzing economic activity by underlining the importance of a wide range of institutions and social hierarchies, their mechanistic account of change or stasis is deeply problematic. Positing that the structures of the global economy shift as a result of forces that are separate from individual and collective actors has led, for example, to descriptions of national and EU administrations as simply writing up a change that was brought about elsewhere. Such an account is wrong in the case of the wine industry. More fundamentally, it seriously underestimates the role of agency in all economic activity: the class agency that this approach concentrates on is merely the product of autonomous economic forces that leave no room for contingency.

More generally, the polarization of debate between institutionalist and regulationist economists has led to a simple and straightforward cleavage between agency and structure. Institutionalists emphasize the strategies individual firms use, while regulationists emphasize macrostructural factors. However, two other schools of thought have attempted to overcome this opposition by putting forward new proposals based on an interactionist approach. They themselves clash on a different level and mark out a new set of theoretical divisions that have their own significant omissions.

Beyond Agency and Structure via Networks? The Limits of Interactionism

Promoters of sociological institutionalism have attempted to move beyond the division between agency and structure by explaining that the two are inextricable. They emphasize embedded agency and thus contend that the strategic action of economic actors takes place in a partially constraining social context. In contrast, researchers who subscribe to actor-network theory propose a move beyond the distinction between structure and agency and argue that the terms of the structure-agency equation do not make sense. Because they refute all forms of structural analysis, they dismiss the very existence of a social context as being outside of, and therefore anterior to, action, reject classic conceptions of agency, and concentrate on the material arrangements that support actors’ economic thought and make coordination between them possible. The tools these two schools provide have been used to analyze the construction and evolution of the wine economy. Despite their differences, they share the same disadvantage of only explaining how markets evolve in terms of interactions between individuals and groups (or objects). They thus limit analysis to the activities of businesses, without taking into account partially autonomous dynamics at work in other spaces that also cause economic reproduction or change.

Sociological Institutionalism: Organizational Networks and Embedded Agency

Sociological institutionalism has positioned itself against institutionalist economics and transaction costs theory without discarding agency (Emirbayer and Mische 1998; Schneiberg and Clemens 2006; Convert and Heilbron 2007; François 2008; Steiner and Vatin 2009; Mische 2011). Indeed, it emerged as a hybrid of two alternative approaches.

One of these approaches is social network analysis. Following Harrison White, authors who adopt this approach postulate that actors use information they draw from their networks of relations through monitoring the behavior of others (White 1970; White, Boorman, and Breiger 1976). This approach interprets markets as frameworks actors refer to when they assess and compare themselves against their respective competitors (their “mutual comparability”: White 1981). This approach was extended by the concept of embeddedness, the idea relationships are not the product of utilitarian calculations of transaction costs but are instead strongly embedded in social contexts (Granovetter 1985, 482). Social network analysts distinguished these networks from both markets and hierarchies because they feature repeated exchanges that generate mutual expectations and relationships of trust. By interacting with each other, firms develop forms of collaborative learning. Their development is thus embedded in social context, a key element that institutionalist economics does not take into account.

Organizational analysis is the second approach that underpins sociological institutionalism. Paul DiMaggio and Walter Powell, its initial main proponents, see institutional organizations as relatively stable social forms that define acceptable actions and place limits on individual expectations. In seeking to clarify the reasons why forms of organization converge, organizational analysts focus on interactions between actors and the relationships between organizations and their environment. The principal argument they put forward is that a quest for legitimacy takes priority over profit seeking. In order to obtain this legitimacy, organizations that are exposed to the same institutional pressures tend to adopt the same visions of reality and the same routines. This concept is referred to as the organizational field. Those who study organizational fields look at “organizatio...