![]()

Part 1

Tourism and Development: Conceptual Perspectives

![]()

1 Tourism: A Vehicle for Development?

Richard Sharpley

Introduction

Tourism is, without doubt, one of the major social and economic phenomena of modern times. Since the early 1900s when, as a social activity, it was largely limited to a privileged minority, the opportunity to participate in tourism has become increasingly widespread. At the same time, distinctions between both tourism destinations and modes of travel as markers of status have become less defined; tourism, in short, has become increasingly democratised (Urry & Larsen, 2011). It also now ‘accounts for the single largest peaceful movement of people across cultural boundaries in the history of the world’ (Lett, 1989: 277), an international movement of people that, in 2012, reached over 1 billion arrivals for the first time (UNWTO, 2013b). In 2013, international arrivals reached 1087 million, a 5% increase on the 2012 total (UNWTO, 2014). Moreover, if on a global basis domestic tourism trips are also taken into account, this figure is estimated to be between six and 10 times higher.

Reflecting this dramatic growth in the level of participation, what has long been referred to as the ‘pleasure periphery’ (Turner & Ash, 1975) of tourism has also expanded enormously. Not only are more distant and exotic places attracting ever-increasing numbers of international tourists – as noted in the introduction to this book, more than 70 countries, including Jordan, Cuba, Peru, Chile, Costa Rica, Vietnam and Cambodia, now receive in excess of 1 million international visitors each year – but also few countries have not become tourist destinations. Even the world’s most remote or dangerous areas are attracting increasing numbers of visitors. For example, in 1997 some 15,000 tourists visited the Antarctic, a figure that had reached 37,552 by 2006–2007 (British Antarctic Survey, 2011), while, prior to the 2003 war, Iraq was promoting itself as a tourist destination, ironically using the slogan ‘From Nebuchadnezzar to Saddam Hussein: 2240 years of peace and prosperity’ (Roberts, 1998: 3). By 2009, tour operators were again officially escorting tourists to that war-torn country and recent reports point to a resurgence of tourism there. Moreover, as evidence of this emergence of tourism as a truly global activity, the United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) now publishes annual tourism statistics for about 215 states.

However, tourism is not only a social phenomenon; it is also big business. Certainly, ‘mobility, vacations and travel are social victories’ (Krippendorf, 1986: 523), yet the ability of ever-increasing numbers of people to enjoy travel-related experiences has depended, by necessity, upon the myriad of organisations and businesses that comprise the ‘tourism industry’. In other words, tourism has also developed into a powerful, world-wide economic force. International tourism alone generated over US$1.075 billion in 2012 (UNWTO, 2013b) whilst, according to the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC), if both direct and indirect expenditure is taken into account then global tourism – including domestic tourism – is a $7 trillion industry, accounting for over 10% of world gross domestic product (GDP) and around 9% of global employment. Such remarkable figures must, of course, be treated with some caution; as Cooper et al. (1998: 87) once observed, ‘it is not so much the size of these figures that is so impressive, but the fact that anybody should know the value of tourism, the level of tourism demand or to be able to work these figures out’. Nevertheless, there can be no doubting the economic significance that tourism has assumed throughout the world.

Owing to its rapid and continuing growth and associated potential economic contribution, it is not surprising that tourism is widely regarded in practice and also in academic circles as an effective means of achieving development. That is, in both the industrialised and less developed countries of the world, tourism has become ‘an important and integral element of their development strategies’ (Jenkins, 1991: 61). Similarly, within the tourism literature, the development and promotion of tourism is largely justified on the basis of its catalytic role in broader social and economic development. Importantly, however, prior to the early 2000s, relatively little attention had been paid in the literature to the meaning, objectives and processes of that ‘development’. In other words, although extensive research had been undertaken into the positive and negative developmental consequences of tourism, such research had, with a few exceptions, been ‘divorced from the processes which have created them’ (Pearce, 1989: 15). Over the last decade, of course, increasing academic attention has been paid to the relationship between tourism and development, including the first edition of this book. Nevertheless, tourism’s alleged contribution to development generally continues to be tacitly accepted whilst a number of fundamental questions remain unanswered. For example, what is ‘development’? What are the aims and objectives of development? How is development achieved? Does tourism represent an effective or realistic means of achieving development? Who benefits from development? What forces/influences contribute to or militate against the contribution of tourism to development?

The overall purpose of this book is to address these and other questions by, in particular, establishing and exploring the links between the discrete yet interconnected disciplines of tourism studies and development studies. In this first chapter, therefore, we consider the concepts of and inter-relationship between tourism and development, thereby providing the framework for the application of development theory to the specific context of tourism in Chapter 2 and the more specific issues in subsequent chapters.

Tourism and Development

As suggested above, tourism is widely regarded as a means of achieving development in destination areas. Indeed, the raison d’être of tourism, the justification for its promotion in any area or region within the industrialised or less developed world, is its alleged contribution to development. In a sense, this role of tourism has long been officially sanctioned, inasmuch as the then World Tourism Organisation (now UNWTO, to distinguish it from the World Trade Organisation) asserted in its 1980 Manila Declaration on World Tourism that:

world tourism can contribute to the establishment of a new international economic order that will help to eliminate the widening economic gap between developed and developing countries and ensure the steady acceleration of economic and social development and progress, in particular in developing countries. (WTO, 1980: 1)

Interestingly, and reflecting the organisation’s broader membership and objectives, the focus of the UNWTO continues to be primarily on the contribution of tourism to development in the less developed countries of the world. In this context, tourism is seen not only as a catalyst of development but also of political-economic change. That is, international tourism is viewed as a means of achieving both ‘economic and social development and progress’ and the redistribution of wealth and power that is, arguably, necessary to achieve such development. (It is, perhaps, no coincidence that, in 1974, the United Nations had also proposed the establishment of a New International Economic Order in order to address imbalances and inequities within existing international economic and political structures). This immediately raises questions about the structure, ownership and control of international tourism, issues that we return to throughout this book.

The important point here, however, is that attention is most frequently focused upon the developmental role of tourism in the lesser developed, peripheral nations. Certainly, many such countries consider tourism to be a vital ingredient in their overall development plans and policies (Dieke, 1989; Telfer & Sharpley, 2008) and, as Roche (1992: 566) comments, ‘the development of tourism has long been seen as both a vehicle and a symbol at least of westernisation, but also, more importantly, of progress and modernisation. This has particularly been the case in Third World countries’. Not surprisingly, much of the tourism development literature has long had a similar focus, with many texts and articles explicitly addressing tourism development in less developed countries (for example, Britton & Clarke, 1987; Brohman, 1996b; Harrison, 1992b, 2001a; Huybers, 2007; Lea, 1988; Mowforth & Munt, 1998, 2009; Singh, T. et al., 1989; Weaver, 1998a).

However, the potential of tourism to contribute to development in modern, industrialised countries is also widely recognised, with tourism playing an increasingly important role in most, if not all, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. In Europe, for example, there has long been evidence of national government support of the tourism sector, in some cases dating back to the 1920s and 1930s, and more recently ‘tourism – along with some other select activities such as financial services and telecommunications – has become a major component of economic strategies’ (Williams & Shaw, 1991: 1). In particular, tourism has become a favoured means of addressing the socio-economic problems facing peripheral rural areas (Cavaco, 1995a; Hoggart et al., 1995; Phelan & Sharpley, 2011; Roberts & Hall, 2001) whilst many urban areas have also turned to tourism as a means of mitigating the problems of industrial decline. Indeed, government support for tourism-related development is evident in financial support for tourism-related development or regeneration projects. For example, one method of disbursing European Union (EU) structural funds for rural regeneration in Europe has been through the LEADER (Liaisons Entre Actions pour la Développement des Économies Rurales) programme. Of 217 projects under the original LEADER scheme, tourism was the dominant business plan in 71 (Calatrava Requena & Avilés, 1993). Thus, just as tourism is a global phenomenon, so too is its developmental contribution applicable on a global basis. What varies is simply the contextual meaning or definition of ‘development’, or the hoped-for outcomes of tourism development.

Therefore, it is important to understand what is meant by the term ‘development’ and how its meaning may vary according to different contexts. First, however, it is necessary to review the reasons why tourism, as opposed to other industries or economic sectors, is seen as an attractive vehicle for development.

Why Tourism?

Throughout the world, the most compelling reason for pursuing tourism as a development strategy is its alleged positive contribution to the local or national economy; as Schubert et al. (2011: 377) summarise, ‘international tourism is recognised to have a positive effect on the increase of long-run economic growth through different channels’. First and foremost, international tourism represents an important source of foreign exchange earnings; indeed, it has been suggested that the potential contribution to the national balance of payments is the principal reason why governments support tourism development (Opperman & Chon, 1997: 109). For many developing countries, tourism has become one of the principal sources of foreign exchange earnings whilst even in developed countries the earnings from international tourism may make a significant contribution to the balance of payments in general, and the Travel Account in particular. For example, in 2010, the UK attracted 29.8 million tourists who collectively contributed to international tourism receipts of £16.9 billion. Whilst this represented just 6.5% of total exports, it offset around 53% of the £31.8 billion spent by UK residents on overseas trips that year (VisitBritain, 2011). It should also be noted that domestic tourism in the UK generated almost £70 billion in direct expenditure, pointing to the importance of domestic tourism in national development and the reason for the government wishing to encourage British people to take domestic holidays rather than travelling abroad. By 2013, overseas visitors spent £20.99 billion, 13% more than in 2012 and it was the first time the £20 billion mark was passed (VisitBritain, 2013b).

Tourism is also considered to be an effective source of income and employment. Reference has already been made to the global contribution of tourism to employment and GDP and, for many countries or destination areas, particularly with a dominant tourism sector, tourism is the major source of income and employment for local communities. In the Maldives, for example, about 26% of the workforce is employed directly in tourism and a further 27% indirectly. In the UK as a whole, tourism directly and indirectly accounts for around 8% of employment although in tourism-intensive areas, such as the English Lake District, well over 50% of employment is tourism related (Sharpley, 2004). It is also one of the reasons why tourism is frequently turned to as a new or replacement activity in areas where traditional industries have fallen into decline. Schubert et al. (2011) suggest that tourism is also pursued as a source of economic growth because, in addition to foreign exchange earnings and income and employment generation, it stimulates local competition and investment in infrastructure, it encourages other economic sectors to develop and may encourage technical and human capital development.

The economic benefits (and costs) of tourism are discussed at length in the literature, as are the environmental and socio-cultural consequences of tourism. Many of these are considered in the context of development in later chapters. The main point here, however, is that the widely cited benefits and costs of tourism, whether economic, environmental or socio-cultural, are just that. They are the measurable or visible consequences of developing tourism in any particular destination and, in a somewhat simplistic sense, tourism is considered to be ‘successful’ as long as the benefits accruing from its development are not outweighed by the costs or negative consequences. What they do not provide is the justification or reason for choosing tourism, rather than any other industry or economic activity, as a route to development.

From a perhaps cynical point of view, the answer might lie in the fact that, frequently, there is simply no other option (F. Brown, 1998: 59). For many developing countries with a limited industrial sector, few natural resources and a dependence on international aid, tourism may represent the only realistic means of earning much needed foreign exchange, creating employment and attracting overseas investment. Certainly this is the case in The Gambia, one of the smallest and poorest countries in Africa. With an estimated average annual per capita income of US$310 amongst its population of 1.6 million, The Gambia lacks any natural or mineral wealth and its economy is largely based on the production, processing and export of ground-nuts. As a result, the country remains highly dependent upon international aid. However, with its fine Atlantic beaches and virtually uninterrupted sunshine during the winter months, The Gambia has, since the mid-1960s, been able to take advantage of the European winter-sun tourism market. Tourism now represents around 11% of GDP and directly provides some 10,000 jobs (Sharpley, 2009a; Thomson et al., 1995). However, because of the extended family system prevalent in Africa, up to 10 Gambians are supported by the income from one job. At the same time, local schools, charitable organisations and environmental projects rely heavily upon income derived directly from tourists whilst, in the absence of scheduled services, regular charter flights to northern Europe provide essential communications and freight services. Thus, despite the fragility of the tourism sector in The Gambia, as evidenced by the collapse of the industry following the military coup in 1994 (see Sharpley et al., 1996), the country had no other realistic choice other than to develop tourism and it now makes a significant contribution to the economy of The Gambia.

More positively, however, a number of reasons may be suggested to explain the attraction of tourism as a development option (see Jenkins, 1980; 1991).

Tourism is a growth industry

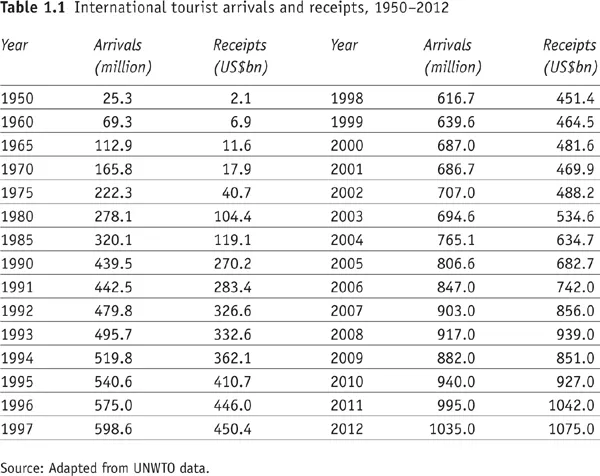

Since 1950, when just over 25 million international tourist arrivals were recorded, international tourism has demonstrated consistent and remarkable growth. Indeed, over the last 60 years it has sustained an overall average annual growth rate of 6.2% in terms of international arrivals and over 10% annual growth in receipts (see Table 1.1).

Interestingly, between 1950 and 2000 the rate of growth in arrivals and receipts declined steadily. For example, during the 1990s the average annual growth in global tourist arrivals was 4%, the lowest since the 1950s (Table 1.2).

Since the start of the new millennium, however, the average annual increase in arrivals has levelled off at around 4.5%, and it would appear that the UNWTO’s long-standing and perhaps rather daunting forecast of 1.6 billion arrivals (and receipts of US$2 trillion) by 2020 will be easily met, if not exceeded (WTO, 1998c), although rises in the cost of oil along with potential ‘green’ taxation on aviation may lead to significant rises in the cost of air travel and, hence, serve to dampen demand in the future, at least for international travel. It must also be questioned whether such growth over the coming decades is sustainable both environmentally and in terms of the enormous investment in infrastructure that would be required. Nevertheless, at first sight tourism as an economic sector has demonstrated healthy growth and, hence, is considered an attractive and safe development option.

Table 1.2 Tourism arrivals and receipts growth rates, 1950–1998

| | Arrivals (average annual increase %) | Receipts (average annual increase %) |

| 1950–1960 | 10.6 | 12.6 |

| 1960–1970 | 9.1 | 10.1 |

| 1970–1980 | 5.6 | 19.4 |

| 1980–1990 | 4.8 | 9.8 |

| 1990–1998 | 4.0 | 6.5 |

Source: WTO (1999b).

However, the overall global figures mask two important factors. First, although international tourism can claim to be a growth sector (and, indeed, has proved to be remarkably resilient to eternal events), certain periods have witnessed low or even negative growth. The OPEC crisis of the mid-1970s, the global recession in the early 1980s and the Gulf conflict in 1991 all resulted in diminished growth figures and, for some countries, an actual drop in arrivals. For example, although worldwide international arrivals in 1991 grew by just 1...