- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book is the first to examine oil constraints and tourism, and addresses one of the key challenges for the tourism industry in the future. It provides an estimate of how much oil tourism consumes globally and summarises state-of-the-art information on oil resources, oil data and public discourse. The volume also offers an analysis of the economic implications of increasing oil prices for tourism and discusses key dimensions relevant for tourism in a post peak oil world. It will be useful for tourism stakeholders globally, postgraduate students in tourism and resource management, ecological economists and those researching issues of resource efficiency, carrying capacity and global environmental change.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tourism and Oil by Susanne Becken in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Energy Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

The failure today to bring the potential reality and implications of peak oil, indeed of peak everything, into scientific discourse and teaching is a grave threat to industrial society.

(Hall & Day, 2009: 237)

1.1 Context

This has been called the Century of Declines (Heinberg, 2007). The planet now holds a population of over 7 billion people, and this number is expected to increase to 11 billion by the end of the 21st century. Along with population growth, economic activity and wealth have increased. Global gross domestic product (GDP) per capita has grown tremendously: more than 13 times as fast as the population (Cox, 2012). This growth is amazing and to some even astonishing. In fact, the last century has defied Malthusian predictions of mass starvation and disease as a consequence of accelerated population growth. The reason is that not only has the population grown exponentially, but so has our use of fossil fuels. In the last 100 years cheap fossil fuels have enabled a massive increase in agricultural productivity, evidenced in the heavy use of machinery, fertilisers and pesticides. In conjunction, mobility has increased to an extent that over 1 billion people are now travelling across borders every year.

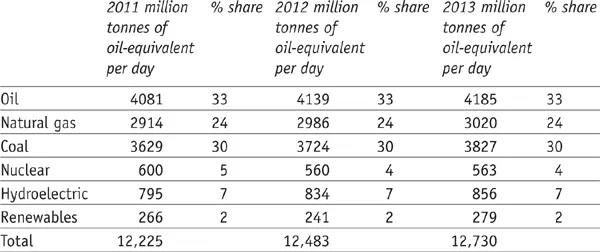

The use of oil, coal and gas has increased, but also that of other natural resources, for example water, copper, phosphate, biomass, grain and meat. Global energy consumption continues to increase, despite the global financial crisis in 2009. As can be seen in Table 1.1, global energy demand in 2012 amounted to 12,730 million tonnes of oil-equivalent (toe) per day. Oil is the most important primary energy source, making up 33% of all use. In 2013, oil consumption amounted to 4185 toe, the equivalent of 91,331 oil barrels per day. The largest increase between 2011 and 2013, however, was observed for coal, with a 5.4% growth. Oil consumption increased by 2.5% between those years – with much of this being met by unconventional oil resources such as tar sands. Natural gas and renewable energy sources have increased by 3.6% and 5.0%, respectively. Renewable energy sources still make up only 2% of all global energy use, and are far from ‘replacing’ fossil fuels.

Table 1.1 Recent global energy consumption: 2011, 2012 and 2013

Note: This table does not include energy extracted from small-scale biomass use, e.g. wood-fired cooking.

Source: British Petroleum (BP) (2014).

In the 1970s, there was a strong interest in population growth and resource constraints, evidenced in a range of scientific publications including the well-known book The Limits to Growth, commissioned by the Club of Rome (Meadows et al., 1974). The oil crises in 1974 and 1979 further highlighted the importance of considering planetary constraints on development. Ecologists were interested in concepts such as carrying capacity, and this was also reflected in tourism and leisure research, where academics focused on growth limitations related to recreational visitation to natural areas. In response to the thinking of that era, a new scientific discipline emerged – ecological economics – that was interested in developing metrics for understanding human environmental footprints and the role of natural capital in economic production. However, as argued by Hall and Day (2009), this focus has changed dramatically, with critical discussions about finite resources and planetary capacities having almost completely vanished from the public and scientific debates.

Instead the focus has moved on to more specific environmental problems, including the impacts of fossil fuel consumption, particularly global climate change. For the last decade (at least), climate change has been central to scientific and political debates on humans’ influence of natural systems. Solutions for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and policy frameworks both for climate change mitigation and adaptation are being discussed intensely by scientists, leading businesses and policymakers. Further, climate change is institutionalised in various formats, including the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate change is a highly prominent issue, and different to resource depletion, of great public interest (Friedrichs, 2011).

More recently, there is increasing evidence of addressing climate change and Peak Oil as joint problems (e.g. Curtis, 2009; Rozenberg et al., 2010). Clearly, both are related to the (excessive) use of fossil fuels. Stoft’s (2008) book Carbonomics. How to Fix the Climate and Charge it to OPEC, for example, highlights the close relationship between climate change and oil security, and seeks to develop effective policy mechanisms to address both. Some have argued that climate change will automatically be solved by shrinking oil resources. Others have pointed to the fact that Peak Oil will only increase climate change risks as we are gradually consuming more carbon-intensive and ‘dirty’ sources of energy. So, while climate chance and Peak Oil seem to be a highly related problem, their solutions often differ – to the extent that climate change mitigation policies could be completely opposite to measures that promote energy security.

In a recent study, McGlade and Ekins (2014) undertook detailed modelling to understand the climate impacts of burning all the fossil fuel that could be exploited. They concluded that the political goal of keeping global warming under the ‘dangerous’ level of 2 degrees Celsius is incompatible with the exploration of carbon-intensive oil resources, such as tar sands or deepwater resources. They argued that if we were serious about climate change, we should not waste economic resources on exploratory drilling of resources that should never be exploited. While discussions of this type are emerging, at this present point they are largely confined to a limited number of academic specialists or advocates. It is not uncommon that ‘anti-oil’ campaigns bring together a number of activists that are either concerned about climate change, Peak Oil, threats to wildlife and the marine life in particular, and other societal issues related to ‘consumption’ (see Figure 1.1).

In the mainstream literature, including elite magazines such as The Economist (Becken, 2014), issues surrounding oil supply and demand are largely addressed by economists and by institutions such as the International Energy Agency (IEA). Mainstream neo-classical economists’ views are built on the premise that ‘something will turn up, when the price of oil is high enough, because something always does’, even though it is known that ‘there isn’t anything conceivable that could replace conventional oil, in the same quantities or energy densities, at any meaningful price’ (BP Exploration Manager Richer Miller, in Newman, 2006: 2). Only a few scientists have pointed to the critical role of energy and the problems associated with its ‘finite’ substitutability (e.g. Daly, 1978, 2008). As a result, Peak Oil is not widely debated as a global economic and environmental risk (Wicker & Becken, 2013). The limited discourse and attention means that many decision-makers (including those related to tourism) may have difficulties conceptualising the idea of Peak Oil.

Figure 1.1 Advertisement for a summit to discuss (and protest against) deep oil exploration in the southern waters of New Zealand, organised by Oil-Free-Otago

Source: http://oilfreeotago.com/links/#

At the same time as the world worries about global financial systems, climate change, and maybe biodiversity loss, many of the resources that we are depending on are reaching capacity – or peak. The peak in oil production is probably the most widely discussed resource peak – and it is the focus of this book. However, other peaks have been identified as well, including peak coal and uranium (Höök, 2010), peak water (Bell, 2009), peak phosphate and minerals (Prior et al., 2012), peak globalisation (Curtis, 2009), and even peak wireless space (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Organisation (CSIRO), 2014). Sometimes the imminence of several peaks requires difficult and precarious trade-offs. For example, the water–energy nexus is increasingly discussed as a challenge, where energy supply depends on water (e.g. for cooling in power plants) and water supply depends on energy (epitomised in desalination plants). It will become increasingly challenging to meet both demands for water and energy.

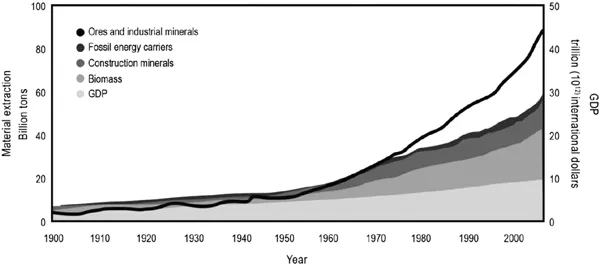

Thus, numerous challenges for maintaining growth and development – including tourism development – are manifesting themselves. Decoupling growth from resource use has been heralded as the approach to overcome physical constraints (see Figure 1.2). Thus, thanks to ever-increasing resource efficiencies, it is argued, continuous growth can be achieved. That means that less resource input is required to achieve the same, or growing, levels of output. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) defines decoupling as a critical step towards a Green Economy in which well-being and equity can be improved while reducing environmental risks and scarcities.

Figure 1.2 Global GDP, biomass and resource extraction in billion tonnes from 1900–2005 – is decoupling possible?

Source: After Krausmann et al. (2009), in UNEP (2011).

One challenge of decoupling is that increasing efficiencies are usually more than compensated for by increases in economic activity, thus leading to overall growth (Tienhaara, 2010). This rebound effect is well-established in the field of energy efficiency, where more efficient devices lead to greater usage and an overall increase in energy use. Should the world not achieve a decoupling and continue business-as-usual, then global resource extraction would triple by 2050 (UNEP, 2011). Others have argued that the 2009 financial crisis highlighted that the current growth model is unsustainable and requires a fundamental change (in Tiernhaara, 2010). Such change is not predicated in the concept of the Green Economy, which has to be seen as a ‘paradigm nudge’ as opposed to a much needed ‘paradigm shift’ (Weaver, 2009).

Peak Oil is one of the most imminent and pervasive challenges to humankind and its existing economies and societies (Hall & Day, 2009). Ninety-five percent of all goods produced around the world depend on the input of oil. Oil is not only used directly as an energy source, but often as the base material of lubricants, plastics, pharmaceuticals, textiles and paints (Zentrum für Transformation der Bundeswehr, 2010). Heinberg (2011: 112) noted ‘Quibbling over the exact meaning of the word “peak”, or the exact timing of the event, or what constitutes “oil” is fairly pointless. The oil world has changed.’

Most people take energy for granted and have little appreciation for the uniqueness and usefulness we extract from fossil fuels. Colin Campbell, one of the leading scientists in the Peak Oil debate, summarised this point as follows:

It was as if oil provided us with an army of unpaid and unfed slaves to do our work for us. It has been calculated that a drop of oil, weighing one gram, yields 10,000 calories of energy, which is the equivalent of one day’s hard human labour. In other words, today’s oil production is equivalent in energy terms to the work of 22 billion slaves. Financial control of the world has led to a certain polarisation between the wealthy West and the other countries which find themselves burdened by foreign debt as they export resources, product and profit. Many people have come to think that it is money that makes the world go round, when in reality it is the underlying supply of cheap, and largely oil-based, energy, that has turned the wheels of industry, fuelled the airliners and the bombers, and generally acted as the world’s blood stream. Midas-like wealth flowed to those who find themselves having a controlling position in the System. (Campbell & Heapes, 2008: 7)

Tourism is very energy-intensive (Scott et al., 2008), and as will be discussed in this book, consumes about 10% of oil-equivalent globally. Thus, as an example, a large number of imaginary ‘energy slaves’ would be required to transport people to and from their holiday destinations. As we will see later in this book, the average tourist who travels by air uses 0.57 barrels of oil per flight. One barrel of oil alone contains the energy of about 23,000 hours of human labour (Heinberg, 2013). Campbell and Heapes’ quote above not only highlights the magnitude of energy supplied by oil, but it also points to the intricate relationship between energy wealth, political power, military conflict and terrorism (The Economist, 2004). Thus, Peak Oil – and the global distribution of supply and demand – is a precarious issue, potentially much more so than global climate change. While tourism is often heralded as a force of good (e.g. as in the 2014 World Travel and Tourism Council Global Summit) and an ambassador for peace, its thirst for the black gold is indirectly adding to geopolitical conflicts over access to oil resources.

1.2 Purpose and Structure of This Book

The introduction above highlights the pervasive and grave risks associated with Peak Oil, both for society broadly and for tourism specifically. Despite the alarming trends outlined above, there is no discussion about Peak Oil in tourism. This book aims to address this important gap. The book acknowledges the relevance of the existing tourism discourse on resource consumption and environmental risks, in particular previous work on tourism and climate change (e.g. Becken, 2013b; Becken & Hay, 2007, 2012; Gössling, 2010; Peeters et al., 2007; Scott et al., 2012). However, by specifically unpacking the threat of Peak Oil and its implications for tourism, this book discusses absolute physical limits to tourism, rather than environmental risks and consumer choices. It therefore also responds to Hall and Day’s (2009) call to bring peak resources back into the academic debate. In the views of this author this is of critical importance to tourism.

This book cannot provide a full analysis of Peak Oil implications for tourism, nor will it be within the scope of analysis to deliver an exhaustive analysis of different stakeholder views, actions and vulnerabilities. However, the book aims to provide a first basis for discussing these important dynamics relevant to the phenomenon of Peak Oil. Substantial knowledge gaps that became apparent while writing this book will be pointed out where relevant.

As this book will show, the consequences of Peak Oil are likely to require a reconceptualisation of tourism. The rationale of this book is therefore to provide essential information on the current status of oil use in tourism, its growth expectations and alternative development pathways in the face of decreasing availability of cheap oil. It is hoped that this book is not only informative to those interested in tourism theory and practice, but that it serves as an eye opener to those interested in sustainable tourism (in the true sense of the word). It is also...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Boxes

- 1 Introduction

- 2 A Thirsty Sector: Oil Requirements of Tourism

- 3 The Sky is the Limit: Growth Expectations for Tourism

- 4 The End of Plenty: Physical Constraints

- 5 Socio-Political Challenges of Addressing Peak Oil

- 6 The Economic Impact of Oil Prices on Tourism

- 7 Pathways to Post-Peak Tourism

- 8 Conclusion

- References

- Index