eBook - ePub

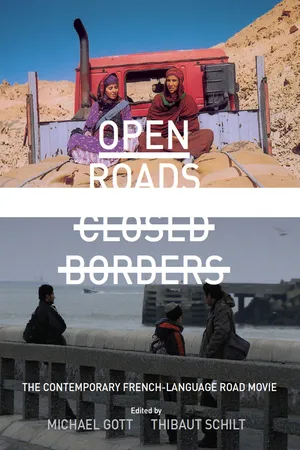

Open Roads, Closed Borders

The Contemporary French-language Road Movie

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Open Roads, Closed Borders

The Contemporary French-language Road Movie

About this book

This is the first collection of essays about French-language road movies, a particularly rich yet critically neglected cinematic category. These films, the contributors argue, offer important perspectives on contemporary French ideas about national identity, France's former colonies, Europe, and the rest of the world. Taken together, the essays illustrate how travel and road motifs have enabled directors of various national origins and backgrounds to reimagine space and move beyond simple oppositions such as Islam and secularism, local and global, home and away, France and Africa, and East and West.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Open Roads, Closed Borders by Michael Gott, Thibaut Schilt, Michael Gott,Thibaut Schilt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Política pública de ciencia y tecnología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

On the Eve of the Journey: Tangier, Tbilisi, Calais

Time and again in road movies the journey is represented as liberation—from a domesticity and a society that are perceived as suffocating, from persecution, poverty and war, or from personal and relational failures. The journey, in this sense, is a narrative device that channels the energies of both protagonist and film; the forward movement guarantees a release of tension, even though a precise destination often does not exist in road movies—thus accounting for the genre’s open-endedness and even penchant for tragic endings. The tension that finds relief through the journey is not only relevant to character psychology, but also to story, in terms of the film’s need to overcome a narrative obstruction, consisting in either inner or external obstacles, which hinder the departure. The energies thus released are at once emotional and aesthetic, inasmuch as the psychological alleviation experienced by the protagonist frequently merges with specific filmic pleasures enjoyed by the spectator. It is on the road that the distinct, kinetic energy and aesthetic dimension of the travel film become actualised.

Travel, of course, is not always synonymic with pleasure, but can run contrary to it. Displacement, exile, diaspora and unproductive or self-destructive wandering, for instance, all evoke a sense of displeasure and even of annihilation of the self, and are often connected to a lack of free agency. However, even when the journey is voluntary and yearned for by the traveller, tension may still be present and materialise in a pleasure/displeasure dynamic.

In contrast to the above-described mobilisation of narrative and concomitant release of tension, a number of French migration road movies of the past decade focus on states of strain and discomfort, for which little or no relief is found through motion. This effect is achieved by focussing on the eve of the journey rather than on the journey itself. In these films, the tension belongs, first of all, to the characters, to the extent that they are either held back or brood over the possibility of departing; however, it also has a much broader dimension that exceeds the personal sphere. The (planned, desired, delayed) journey becomes, indeed, the locus of the manifestation of tensions which characterise and affect life in contemporary French and European societies at large, and which have to do with pressures and strains created by factors such as border management, economic polarisation and political discourses on matters of migration, citizenship, mobility and identity.

The three examples of this trend that this essay will consider are Loin/Far (André Téchiné, 2001), Depuis qu’Otar est parti … /Since Otar Left (Julie Bertucelli, 2003) and Welcome (Philippe Lioret, 2009). While diverse in style and ambition, they share an interest in matters of legal and, especially, illegal immigration; and a hindered journey is at the core of their narrative and thematic concerns. In addition, they all fall in the category that Carrie Tarr has tentatively called ‘pre-border-crossing films’. According to Tarr, in these films the ‘mise-en-scène of destabilised, unsettling border spaces combined with a foregrounding of the migrant’s subjectivity and agency invite the western spectator to understand their choice of deterritorialisation and sympathise with their resulting vulnerability and isolation’ (Tarr 2007: 11). Similarly to Tarr, I here look at films that we can call ‘French’ while being conscious of the fact that ‘the transnational elements mobilised in films about migration call into question the validity of analysing border crossings within the limited framework of a national cinema, or even within the larger context of European cinema’ (Tarr 2007: 9). The first two of these films are international co-productions (between France and Spain and France and Belgium respectively). Loin was co-written by Téchiné with the Moroccan writer Faouzi Bensaïdi, ‘and is moreover quadrilingual, with dialogue in French, English, Spanish and Arabic, as well as a prayer in Hebrew’ (Marshall 2007: 115). Both other films also are multilingual: a French production, Welcome includes much dialogue in English, as well as some Kurdish and Turkish; in Depuis qu’Otar est parti … Georgian, French and Russian are spoken.

These films’ transnationalism is of course central to their redefinition of both immigrant and French identities, as well as of ideas of Eurocentrism. In her analysis of road movies produced in the 1990s and 2000s in Slovenia, Polona Petek has noted a tendency in recent European road movies to go in ‘the direction of immobility or, more accurately, the direction of stalled or refused mobility’ (Petek 2010: 219). Petek reads such tendency positively, with reference to the films’ constructive critique of both Eurocentrism and of the elitist western view of cosmopolitanism as coinciding with capitalism, which they replace with the project of an alternative, non-Eurocentric cosmopolitanism. In particular, for Petek these films’ choice to support the ‘interweaving of pro-European and yugonostalgic discourses, grounded on both sides of the European border, instantiates or, at least, paves the way for such a multi-sited cosmopolitanism’ (222). In the French pre-border-crossing films I explore here, instead, while the stalling of movement certainly amounts to a critique of Eurocentrism, it does not result in a clear alternative cosmopolitan project, but becomes the expression of profound social tensions.

In my essay, I will reflect on the centrality (or, indeed, marginality) of France to these films. Each is set in a location that can be described, in terms of global geopolitics, as peripheral with reference to both France and Western Europe: in Tangier, Tbilisi and Calais respectively. By talking from the margins, each of these films reconfigures the continent and the place that France thinks itself to occupy in it. As well as examining tension from the point of view of character psychology and of the films’ broad thematic concerns, I will also discuss it in narratological terms—and show how, rather than the open-endedness of the typical road movie narrative, these films are characterised by stasis, circularity and repetition, in a way that simultaneously compounds the characters’ feelings of entrapment and contributes to the idea of a socio-cultural tension that cannot find release in the transformative experience of the journey.

South/North, East/West

The globalising discourses that became predominant in the 1980s and 1990s posited what was substantially to become a borderless world: ‘Faced with the onslaught of cyber and satellite technology, as well as the free unimpeded flow of global capital, borders would—so the globalization purists argued—gradually open until they disappeared altogether’ (Newman 2006: 172). The past decade, possibly as a reaction to these discourses, has seen an interdisciplinary renaissance of border studies; similarly, these three films, which span the whole decade, decidedly reiterate the importance of barriers—physical, social, legal, economic—and engage with the border as a process rather than as a static notion. Borders pertain, of course, to the sphere of power, and power relations are a main factor in border demarcations (Newman 2006: 175), as well as in the exercise of the control and restriction of movement. The differential power that becomes evident around borders is one of the sources of the tension that emerges in the chosen films.

Mindful of the fact that borders are not limited to the actual line of demarcation between two countries, Klaus Eder has suggested that distinctions must be drawn between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ borders. Hard borders function not only on the basis of actual barriers but also on the existence of soft boundaries that have to do with the production of meaning:

The difference between both is that the former, the hard borders, are institutionalized borders, written down in legal texts. The soft borders of Europe are encoded in other types of texts indicating a pre-institutional social reality, the reality of images of what Europe is and who are Europeans and who are not.

(Eder 2006: 256)

The films I here consider represent both hard and soft borders and, arguably, participate in the shaping of the latter, for they produce images of what Europe is and is not. The visibility of a film such as Welcome in French and European political discourses on immigration corroborates this statement: the film was screened in both the French and the European parliaments and on 2 March 2009 the director Lioret debated the issue of French legislation on illegal immigrants with Éric Besson, Minister of Immigration, Integration, National Identity and Mutually-Supportive Development in the government of François Fillon, on the France 3 programme Ce soir (ou jamais!).

The three films comment on the two main frontiers of Europe—southern and eastern; and each does so while placing France (which is evoked either directly or via its conspicuous absence) at the centre of a reconfiguration of the continent. The films, furthermore, frame France from the north, south and east respectively, thus looking at its three most important hard borders.

More specifically, Welcome, which takes place in Calais and is narratively projected towards England, is set against the backdrop of concepts of the South/North divide, one which overturns the original idea of European civilisation as constructed from the south and the Mediterranean. Today, the prevalent discourse sees the North as a civilising force set in contrast to the ‘problem’ of a South depicted as inexorably lagging behind in the modernisation process. In Welcome, it is northern Europe, namely England, that attracts immigration, and not France, which is perceived as a border itself—as the southern frontier of the civilised North.

Loin also looks at the South/North divide, and in particular at the southern border of Europe, from the distinctive point of view of Arabic North Africa. As Eder reminds us, this area, in contrast to Black Africa, could potentially be considered European, since ‘[i]t could claim a long common tradition of being part of the Roman Empire, of an intellectual common ground over centuries of the Christian-Islamic culture up to the colonization of North Africa by the French’ (Eder 2006: 263). Yet, this border remains fixed, and the southern frontier of Europe has now moved to the southeast, coinciding with Turkey. In Loin also France is no longer central to the emigrants’ dreams and is indeed practically irrelevant to the narrative. A French truck driver travels the Spain/Morocco commercial route in search of adventure; of his Moroccan friends, one dreams of Spain and a generic Europe, while the other considers immigrating to Canada. France is thus drastically repositioned, albeit in a world that is still conditioned by the visible inheritance of French colonisation.

Finally, Depuis qu’Otar est parti … focuses on the East/West boundary.

The East provides the second frontier of Europe. In the narrations of this frontier, the ‘second other’ of Europe was constructed. This East appears as Russia, providing a referent for something that Europe is different from. From Tsarist Russia to Communist Russia, a particular sense of threat was imagined. The East is the space from once [sic] the ‘Mongols’ came, then the ‘Russians’ and finally the ‘Soviet Communists’.

(Eder 2006: 264)

This is the only film in which France is still regarded a utopian destination by the characters; seen from beyond the post-Soviet eastern border, thus, France is still equivalent with old Europe. The film, however, shows how the repositioning of the West/East border after the dissolution of the Soviet Bloc is challenging the idea of what being European means. In Georgia, a country wedged between Russia and Turkey, we get acquainted with characters who not only speak French, but also feel French. In spite of its spiritual proximity with Paris, though, post-communist Georgia is as distant from France as it was in the past, if not more.

Indeed, what we are given to see in each of these films is far from the idealised borderless Europe of free movement. On the other hand, the question of how to cross borders constitutes an almost insurmountable problem for all non-western characters. Europe looks very much like a fortress here—though its borders are not completely impermeable. What is especially significant is the way in which these films challenge Eurocentrism, and consequently the idea of France’s hegemonic position within Europe; in fact, they reposition the country as a sort of borderland. Even when it is the chosen destination for emigration, its harsh reality clashes so profoundly with the characters’ dreams that it compellingly suggests the end of France’s centrality to an idea of Europe based on the inheritance of the Enlightenment and on discourses that equate modernity with progress and liberal capitalism with democracy.

Because of the statement that the three films make through their choice of marginalising France, it seems productive to pay some attention to how they engage with actual margins. By the term ‘borderlands’ I here intend spaces that are constructed as limens and frontiers and that function as representations of soft borders and, indirectly, of ideas of France and Europe according to the discursive axes South/North and East/West.

Borders and Borderlands

It is not necessary for a film to include images of a border in order to evoke it. Equally, crossing a border does not necessarily imply the physical act of traversing the line of demarcation between two countries:

For many travellers, the border crossing point is located at the check-in counters at the airports in their home countries. It may be the airline officials who undertake the task or, as is increasingly the case in Canada and some other western countries, the creation of a micro piece of ex-territory under US jurisdiction in the foreign airport territory.

(Newman 2006: 178)

Similar to airports, micro-pieces of another country may be found in large ports. This is the case of Loin, which foregrounds ports as borderlands, and sets significant sections of its narrative in the ports of Algeciras, the largest Spanish city on the Bay of Gibraltar, and especially of Tangier, Morocco, situated at the western entrance to the Strait. The entire city of Tangier can be seen as a borderland, as remarked by André Téchiné himself when he said that Tangier is one of those ‘frontier-spaces, places that are both bridges and barriers, places of transit’ (quoted in Marshall 2007: 118).

Serge (Stéphane Rideau), a young French truck driver, can cross over legally, though not without delays, given the controls implemented in order to police the intense trafficking of both drugs and people between northern Africa and southern Europe. His friend Saïd (Mohamed Hamaidi), instead, is one of the many Moroccans who converge on Tangier and hang around the port waiting for an opportunity to hide under a lorry and cross over to Spain. Beaches are typical sites of narratives on the crossing of the Strait of Gibraltar, as can be inferred from Jonathan Smolin’s examination of both Moroccan novels and films on the illegal emigration, all of which feature the patera, ‘a small, fragile fishing boat precariously crammed with some twenty-five immigrants’ (Smolin 2011: 74). The beach (though not the patera) also features in Loin, as a limen where bodily pleasures—swimming, running, acrobatics—are sought and practised, and from which Moroccans look longingly at the Spanish coast on the other side of the Strait. But the true borderland in Loin is the port; here, in spite of the incessant transcontinental circulation of goods, the demarcation between two sides, and indeed two worlds—North and South, neoliberal Europe and developing Africa, First and Third World, Schengen and non-EU, former coloniser and ex-colonies—becomes most evident. As Étienne Balibar has noted, ‘globalization tends to knock down frontiers with respect to goods and capital while at the same time erecting a whole system of barriers against the influx of a workforce and the “right to flight” that migrants exercise in the face of misery, war, and dictatorial regimes in their countries of origin’ (Balibar 2003: 37).

Arguably, the port is at once a small-scale version of the global melting pot, a microcosmic rendition of the tensions between the north and the south of the world, and a representation of the conflict between two competing forms of power: the state and organised crime. The question of where power and rights reside, however, is profoundly problematised in this borderland: far from being organised according to a clear-cut, binary model of spatial division (here/there, Europe/Africa, legal/illegal), the port is a hybrid space in which different logics and laws meet, clash and coexist and in which borders can be negotiated in various ways. The port of Tangier is a borderland because it is neither Morocco nor Europe; it is not fully Morocco because it is also a micro-piece of Europe, and it is not fully Europe because Moroccan custom police and Moroccan traffickers both make their claims on it. The only people who have no rights to be there at all are the ordinary Moroccans; even a bike taxi is stopped this side of the fence, and Saïd can only enter the port freely if accompanied by Serge.

Vehicles are prominent in Loin, including bikes (giving the impression of a great mobility, only defeated by the natural barrier of the sea, Saïd rides everywhere at full speed what one is tempted to call a postcolonial Peugeot); scooters (one is owned by the wealthier Sarah (Lubna Azabal), who has inherited a guesthouse from her mother); old cars; and Serge’s lorry. It is appropriate to ‘read’ these vehicles in terms of the characters’ dissimilar levels of mobility and freedom. In particular, the tragic episode of Saïd’s stolen bike, concluded by the thief’s death, lends itself to an exploration of neorealist themes in the film, and of its relationship with both Vittorio De Sica’s Ladri di biciclette/Bicycle Thieves (1948), to which direct homage is paid by Téchiné, and, indirectly, with La Graine et le mulet/Couscous (Abdel Kechice, 2007), another film about the French/Maghrebi cultural divide set in a port city (Sète) which references De Sica’s landmark post-war drama. However, what I prefer to do here is propose a reflection on Serge’s lorry as another instance of the presence of the borderland in Loin.

When showing his new French-registered truck to a deeply impressed Saïd, Serge describes the vehicle’s features with some pride (he even calls it ‘the Ferrari of trucks’). The lorry is evidently framed as state-of-the-art northern European machinery (it’s a Swedish-made Scania), as well as an actualisation of the western world’s ability to translate its aggressive neoliberal credo into advanced technology and unstoppable mobility. Indeed, the lorry puts together scientific innovation and commercial dynamism, thus confirming Europe’s traditional force of penetration into less industrialised regions. It...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: On the Eve of the Journey: Tangier, Tbilisi, Calais

- Chapter 2: The Constant Tourist: Passing Intimacy and Touristic Nomadism in Drôle de Félix

- Chapter 3: Brittany, No Exit: Travelling in Circles in Manuel Poirier’s Western

- Chapter 4: Troubling Return: Femininity and Algeria in La Fille de Keltoum

- Chapter 5: Going Nowhere Fast: On the Road in Contemporary Algeria in Tariq Teguia’s Rome plutôt que vous

- Chapter 6: Times on the Road: Identity and Lived Temporality in Benoît Jacquot’s À tout de suite and L’Intouchable

- Chapter 7: Tourism and Travelling in Jean-Luc Godard’s Allemagne 90 neuf zéro and Éloge de l’amour

- Chapter 8: Under Eastern Eyes: Displacement, Placelessness and the Exilic Optic in Emmanuel Finkiel’s Nulle part terre promise

- Chapter 9: Nowhere to Run, Somewhere to Hide: Laurent Cantet’s L’Emploi du temps

- Chapter 10: Traffic in Souls: The Perils and Promises of Mobility in La Promesse

- Chapter 11: Mobility and Exile in Claire Denis’s 35 rhums

- Chapter 12: Gatlif’s Manifesto: Cinema is Travel

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

- Back Cover