eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Polish Media Art in an Expanded Field

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Polish Media Art in an Expanded Field

About this book

From an Eastern nation on the global periphery to a European neoliberal democracy enmeshed in transnational networks, Poland has experienced a dramatic transformation in the last century. Polish Media Art in an Expanded Field uses the lens – and mirror – of media art to think through the politics of a post-socialist 'New Europe', where artists are negotiating the tension between global cosmopolitanism and national self-enfranchisement. Situating Polish media art practices in the context of Poland's aesthetic traditions and political history, Aleksandra Kaminska provides an important contribution to site-specific histories of media art. Polish Media Art demonstrates how artists are using and reflecting upon technology as a way of entering into larger civic conversations around the politics of identity, place, citizenship, memory and heritage. Building on close readings of artworks that serve as case studies, as well as interviews with leading artists, scholars and curators, this is the first full-length study of Polish media art.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

The Country on the Moon: Or, Artists Reclaim the Polish Site

Eastern European cultures must learn to stand by their own strength.

– Czesław Miłosz (1990/1953)

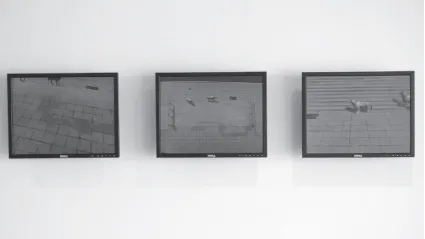

In Jakub Jasiukiewicz’s Canis Lupus Polonus (The Polish Wolf) (2008–2010), roaming wolves have overtaken the wild landscape of the Polish city. Canis Lupus (Latin for grey wolf) plays on the idea of Poland as an untamed wilderness with nary a sign of civilization, unresponsive to the “progress” and “civility” of the West. The artist describes it as a reflection on “the stereotypical way of thinking about East-Central Europe as a deep and wild province” (Jasiukiewicz n.d.). The work has been exhibited numerous times, including at the WRO Mediations Biennale in Wrocław in 2010. It consists of an interactive installation drawing on strategies and technologies of surveillance, whereby four cameras are installed to monitor a sidewalk and film the movement of passers-by. The viewer is located in a gallery with windows overlooking this sidewalk. Three screens mounted onto the window display the scene under observation so that the viewer can at once see the real action and the images on the screens. These screens display the sidewalks from the different perspectives being monitored, the image looking like something from an analogue CCTV system, complete with grey scale, noise, and other imperfections (Jasiukiewicz n.d.). But instead of displaying people, Jasiukiewicz manipulates the image so that each human form is transformed into a 3D avatar of a wolf. What the viewer sees then is a CCTV-like monitoring system with wolves walking and crossing this city space (see Figures 4–6). The project is as much about surveillance as it is about stereotypes of “Polishness,” and in this, Jasiukiewicz in many ways echoes the sensibilities of his generation (he was born in 1983), exploiting a tongue-incheek rapport with Polish history and politics, as well as an unaffectedness with being a “Polish” artist (personal communication, 22 May 2010). The wolf is a complicated and important figure, one that plays upon historical stereotypes of “Poles…as conspirators, revolutionaries, anarchists, and even barbarians, inhabiting ‘swamps, woods and marches on which wolves and bears swarm in packs and endanger the roads’” (as quoted in Castle and Taras 2002, 17). Until a recent resurgence, the wolf had been extinct in “almost all of Europe” except for the “largest concentrations…in the former Soviet Union” (Busch 2007, 22) so that the wildness associated with a wolf’s territory was for a long time located in ECE.1 Metaphors tied to wolves are two-sided: the wolf has been regarded as a symbol of “avarice, viciousness, and guile” (Busch 2007, 99), but also features prominently in certain foundational myths (from Rome to Lithuania), an omen of victory or luck. Drawing on these two-sided connotations, Jasiukiewicz’s wolf may be wild, but perhaps he is also the keeper of the land. Moreover, the wolf’s small pack existence may also offer a way of conceiving of a people, representing the space and strain between individualism and collectivity in the formation of a society. On the surface, then, Canis Lupus creates a surrealist image that takes literally the derogatory stereotype of Poland as wild by drawing on the negative association with wolves. The counterpoint, however, is the symbolism of the wolf as a protector of territory through the vigilance of the pack. In doing so, Canis Lupus alludes to the process of establishing a new set of expectations about Polish society and its place within a globalized world and questions whether “the term ‘East-Central Europe’ is still eligible in the discussion about the contemporary world” (Jasiukiewicz n.d.).

Figure 4: Jakub Jasiukiewicz, Canis Lupus, 2009. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 5: Jakub Jasiukiewicz, Canis Lupus, 2009, output & input (video). Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 6: Jakub Jasiukiewicz, Canis Lupus, 2009. Wolf model. Courtesy of the artist.

The Polish site provides an intricate case for exploring the local dimensions and reverberations of global cultural and political change, one that presents the multifaceted tensions that not only continue to divide Europe into East and West but also make “Europe” and the “European” difficult, if not impossible, categories to define. While this is certainly true in 2004–2009, the question of “Europe” continues to cause problems, so much so that, in large measure, there is a consensus that “no one has even convincingly defined what ‘Europe’ is—geographically…or conceptually” (Langenbacher 2012, 216). Analyses of contemporary Poland are inevitably enmeshed in the persistent debates on modernization and difference that are still creating divisions between the “old” and “new” capitalist democracies in Europe. Therefore, while belonging to the EU has been for some time the definite measure of “Europeanness” (Berezin 2003; Guibernau 2011), it is unclear whether, despite Poland’s joining of this union in 2004, it has in fact been treated as equally European, cosmopolitan, and a peer in global cultural participation and exchanges. In those first five years of European integration, along with a certain relief at finally being part of “Europe,” there was also a need to establish what this meant for Polish identity, and to understand the importance of self-enfranchisement within the context of belonging to the EU, that unofficial marker of being European, however problematic a notion it may be. As noted by John Tomlinson, in a globalized culture, people routinely “negotiate a portfolio of identities” (2011, 285) so that “nobody is only a European” (Beck 2012, 654). In other words, being of European identity does not eliminate the other allegiances that people and societies have developed over centuries. Chantal Mouffe ventures, “at least for the foreseeable future, national forms of allegiance are unlikely to disappear, and it is futile to expect people to relinquish their national identity in favour of a postnational European one” (2012, 629). However, in those critical early years of EU integration, Slovenian scholar and activist Rastko Močnik warned that the East was in fact too easily letting go of its localized particularity and grounded historicity for the sake of global connectivity, cosmopolitanism, assimilation, and entry into the “the serene firmament of universality” that the West represents (2006, 344). This created a situation in which there were “two visions of Poland struggling to co-exist” (as quoted in Slackman 2010). While on the one hand there was a desire to belong to Europe and the West, on the other there was also a fear that in doing so Poland would lose itself in the name of inclusion. Within this context, it had to define and claim its space within European and global networks and imaginaries, but not at the expense of its own identity and history (Marciniak 2009), of its own “we” (Mouffe 2012). Indeed, Poland’s “European” negotiation was and continues to be emblematic of the ways in which Europe itself is “being rethought in eye-opening ways…for example, where it offers a test case for not just applying but also recasting ideas about ethnicity and nation, culture and citizenship, borders and belonging” (Felski 2012a, vi).

European identity is at a critical juncture across Europe, not just its eastern regions. Anthony Smith for example describes it as “vacuous, nondescript, lifeless” (quoted in Felski 2012a, viii), and citizens of the EU member states have repeatedly confirmed a general, if fluctuating, ambivalence towards claiming a European identity.2 Europe itself “is undergoing an existential crisis in which its fundamental meaning is being questioned” (Bottici and Challand 2013, 9; Beck 2012; Langenbacher, Niven, and Wittlinger 2012b; Felski 2012b). And though the European project has been “largely hailed as a success” in the sense of an “Europeanization of national polities, economies, and societies,” these convergences have not “been accompanied by the emergence of a ‘European citizen’ or a common European identity. Quite the contrary…any national societies have become increasingly Euroskeptic” (Langenbacher, Niven, and Wittlinger 2012a, 1). As such, there is a sense that the European project is at a crossroads, that while there needs to be more integration among nations if the EU is to survive, this is challenged by the ongoing desire for collective identification as is manifested in the current reinforcement of national and regional identities (Mouffe 2012, 2013). National identities have proven resilient, so that while the mechanisms have effectively been put in place for Europe to integrate via institutions, laws, and policies, it is now “culture” that is being “widely invoked as a solution to the divisions within Europe—on the grounds that economic and political ties between nations are not sufficient” (Felski 2012a, vi).3 As Clara Bottici and Bruno Challand point out, however, this emphasis on building up the symbolic dimension of European identity (through symbols like the European flag and anthem, or figures like the Greek heroine Europa or figures like Napoleon) is posed to fail, because “they are implicitly based on a model (that of the nation-state) unsuited to supranational polity such as the EU” (2013, 43). One way of addressing, rather than masking, the lack of commonality is noting the degree to which collective memory, as a fragmented and divided recollection of the past, enforces continued rifts between East and West (Pakier and Stråth 2010; Bottici and Challand 2013). To overcome this fragmentation, some argue, there needs to be a push to develop a shared and collective identity through a reimagination and rewriting of a common, if divided, past, memory, and history (Eder and Spohn 2005; Rigner 2012; Felski 2012b; Langenbacher, Niven, and Wittlinger 2012b). Mouffe makes a similar observation in her application of democratic agonism to the case of European integration and a postnational unified identity, whereby Europe’s “aim should be to create a bond among different nations, while nonetheless respecting their difference. The challenge of European integration resides in combining unity and diversity, in creating a form of commonality that leaves room for heterogeneity” (2012, 634). Critic and curator Zdenka Badinovać (2009) has even ventured that ECE artists are especially capable of offering alternatives to homogenizing forms of globalization provided they incorporate their experiences into their work rather than omitting them for fear of distancing a Western audience. In other words, the artist is particularly needed to present critical perspectives on the everyday politics of site, to offer new imaginations and new knowledge, and, conversely, in the Polish case, this criticality also works as a repoliticization through relocalization of artistic practice. This kind of awareness of site through art offers a way of reaffirming the site-specificity essential for Polish self-enfranchisement, which is vital for political imagination, beginnings, and actions even in a world eager to erase and blur borders.4 As Marshall McLuhan observed, since artists are a culture’s early warning system (1964), artistic practices can provide an unparalleled window into the transitions of a society, a way of, in this case, accessing or engaging with the complexities of global citizenship and local resistance.

On Site

To arrive at the idea of the site, we must make our way through the currently rather unpopular modernist idea of the nation. The end of the Cold War shook the world’s trust in the ideals of the nation, having just witnessed and lived through the divisions that wars create. The public was reacting to nationalism’s dark side, and was eager to forget all about the xenophobia, hatred, and violence perpetrated in the name of one’s nation. Soon, all nationalism was equated with ethno-nationalism, leaving behind the notion of the nation as a “common project, mediated by public discourse and the collective formation of culture, [rather] than simply an inheritance” (Calhoun 2002, 152). The formation of the EU in 1993 (following in the footsteps of the European Economic Community created in 1957) exemplified this urge to consolidate citizenships and form bonds and communities across borders. But, importantly, the public came to forget the political effectiveness of the national framework and that “national struggles in much of the world were among the few viable forms of resistance to capitalist globalization” (Calhoun 2007, 11; Smith 1995; Berezin 2003).

Historically, there have been two well-rehearsed lines of thought on the origin of nationalism: the first primordial or essentialist argument is one based on ancient or natural ethnic divisions, and an ethnicity that is “given and immutable” (Calhoun 2007, 61) and which engenders an emotional response, bond, and loyalty (Smith 1995). This is the nation as cultural or ethnic, and as a community of attachment (Berezin 2003; Brubaker et al. 2006). The second locates the nation and nationalism as firmly unrelated to ethnic claims, and where state formation precedes the development of nations and nationalism. This is the state or civic nation, a community of affinity in which the constructed nature of nationalism is emphasized. Here, nationalism is absolutely connected to notions of modernity and the rise of the nation-state. This account explains the situation in ECE, where “the rationality of nation-building was not embedded…until very much later” (Wagstaff 2012, 109). Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, and Belarus, for example, form a territory that has had fluid or no borders for centuries, including when it was the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the largest European state of its time. The distinct nation-states only emerged after the Cold War as a strategic and deliberate showcase to Western Europe of an ability to undertake peaceful negotiations over territory (attaining “European standards”) (Snyder 2003). At this stage, the demarcation of borders had little to do with collective identities tied to feeling “Lithuanian” or “Polish,” as peoples from a variety of ethnic backgrounds lived across the whole region and multilingualism made it at times unclear how to situate or demarcate the population definitely or clearly. Even once borders were established, concerted effort was required to establish nation-states, as areas defined by common language, territory, and a shared collective “national,” in the sense of ethnic, identity. These very successful nationalisms often obscure the fact that they are very recent, and that in this part of Europe, they emerged after the multiculturalism that defined this region for centuries, something which will be further addressed below.5

The arguments between the so-called traditional and modern views of nationalism are not necessarily productive (Calhoun 2002; 2007). An alternative approach considers nations and nationalism as formed through active and shared social, political, and cultural participation and as understood above all as a political solidarity, one that transcends cultural differences, that is essential for the practice of democracy. In this way, the nation can be understood not as an absolute, self-obvious, predetermined, defined category, but as an institution, a discursive practice, or an imaginary (Smith 1995; Anderson 2006; Calhoun 2007). In this way, it functions “as classificatory scheme, as cognitive frame” (Brubaker et al. 2006, 16). For sociologist Rogers Brubaker, understanding nationalism, nationhood, and “nationness” must be done through the “practical uses of the category ‘nation,’ the ways it can come to structure perception, to inform thought and experience, to organize discourse and political action” (1996, 7). Fellow sociologist Craig Calhoun offers that nationalism is best defined as a discursive formation, a working towards claims of political autonomy and self-determination, where a nation is a people of a country that are internally unified “with common interests and the capacity to act” (2007, 48).

The nation-state has long been in a period of “decline” or “crisis” (Berezin 2003, 3), some even boldly asserting that the era of nation-state is over and/or that we have entered a postnational age characterized by the dissolution of the nation as a primary organizational structure in global relations (Harvey 1989; Appadurai 1996; Habermas 2001; Bauman 2004). According to these claims, individuals are no longer primarily bound by their citizenship, but rather by their participation within various deterritorialized digitallyfacilitated communities. The idea that people are now more attached to these ephemeral types of identities has taken precedence, so that the placeless and mobile structures of digital networks and relationships have in some cases been perceived to be more politically effective and coherent than those based on the nation-state. This is because they are often formed with an explicit unifying goal or interest, and act as a means of organization in a world that is desynchronized from historical community and place (Urry 2007). In this context, notions like postnational citizenship (Habermas 2001) or cosmopolitan solidarity (Soysal 1995) have offered illuminating ways of thinking about the new formations that have emerged alongside the liquification of modernity (Bauman 2000) and its cross-border networking, movement, and exchange. However, despite the assertion that these new kinds of patterns of attachment to a-historical and placeless communities, networks, or assemblages have superseded the seemingly obsolete category of the nation, it has remained questionable whether the sense of belonging one associates to a physical place and the political power that emerges from civic identities has become redundant. Postnationalism has therefore been criticized as not fitting well with actual and experienced political realities (Eder and Giesen 2001; Berezin 2003), and some have rather argued for the ongoing—even urgent—need to think critically about the nation-state to elucidate negotiations of identity and culture in regions with alternative histories of democratization, modernization, and global integration, such as ECE, as one of the few viable forms of resistance to globalization (Calhoun 2007). Indeed, whether the crisis of the nation “will lead to the end of the idea of the nation or rather to new rearticulations of nationalism is still difficult to predict” and it is as of yet premature to “make conclusions about an unpredictable future (cf. the ‘postness’ of nationalism)” (Reestorff et al. 2011, 23, emphasis in original). After all, everyday experience remains lived at a local level, one still understood as a place existing in space and time. Allegiances to different kinds of “memory-less” and “context-less” networks have so far not only failed to assuage the feelings of rootless-ness, isolation, solitude, and alienation that have become characteristic and symptomatic of our el...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Country on the Moon: Or, Artists Reclaim the Polish Site

- Chapter 2: Media Art, the Expanded Field: Legacies of Experimentation

- Chapter 3: The Many Stories of Site: Looking Back to Move Forward

- Chapter 4: Spaces of Appearance and Communication: The Public and “Me”

- Chapter 5: Fantasies of a Media Age: Mediations of Self and Site

- Coda

- References

- Index

- Back Cover

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Polish Media Art in an Expanded Field by Aleksandra Kaminska in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & European Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.