1

THE VILLAGE

EMERGES

IN THE MODERN WORLD THE VILLAGE IS MERELY A very small town, often a metropolitan suburb, always very much a part of the world outside. The “old-fashioned village” of the American nineteenth century was more distinctive in function, supplying services of merchants and craftsmen to a circle of farm homesteads surrounding it.

The medieval village was something different from either. Only incidentally was it the dwelling place of merchants or craftsmen. Rather, its population consisted of the farmers themselves, the people who tilled the soil and herded the animals. Their houses, barns, and sheds clustered at its center, while their plowed fields and grazing pastures and meadows surrounded it. Socially, economically, and politically, it was a community.

In modern Europe and America the village is home to only a fraction of the population. In medieval Europe, as in most Third World countries today, the village sheltered the over-whelming majority of people. The modern village is a place where its inhabitants live, but not necessarily or even probably where they work. The medieval village, in contrast, was the primary community to which its people belonged for all life’s purposes. There they lived, there they labored, there they socialized, loved, married, brewed and drank ale, sinned, went to church, paid fines, had children in and out of wedlock, borrowed and lent money, tools, and grain, quarreled and fought, and got sick and died. Together they formed an integrated whole, a permanent community organized for agricultural production. Their sense of common enterprise was expressed in their records by special terms: communitas villae, the community of the vill or village, or tota villata, the body of all the villagers. The terminology was new. The English words “vill” and “village” derive from the Roman villa, the estate that was often the center of settlement in early medieval Europe. The closest Latin equivalent to “village” is vicus, used to designate a rural district or area.

A distinctive and in its time an advanced form of community, the medieval village represented a new stage of the world’s oldest civilized society, the peasant economy. The first Neolithic agriculturists formed a peasant economy, as did their successors of the Bronze and Iron Ages and of the classical civilizations, but none of their societies was based so uniquely on the village. Individual homesteads, temporary camps, slave-manned plantations, hamlets of a few (probably related) families, fortresses, walled cities—people lived in all of these, but rarely in what might be defined as a village.

True, the village has not proved easy to define. Historians, archeologists, and sociologists have had trouble separating it satisfactorily from hamlet or settlement. Edward Miller and John Hatcher (Medieval England: Rural Society and Economic Change, 1086-1343) acknowledge that “as soon as we ask what a village is we run into difficulties.” They conclude by asserting that the village differs from the mere hamlet in that “hamlets were often simply pioneering settlements established in the course of agricultural expansion,” their organization “simpler and more embryonic” than that of the true village.1 Trevor Rowley and John Wood (Deserted Villages) offer a “broad definition” of the village as “a group of families living in a collection of houses and having a sense of community.”2 Jean Chapelot and Robert Fossier (The Village and House in the Middle Ages) identify the “characteristics that define village settlement” as “concentration of population, organization of land settlement within a confined area, communal buildings such as the church and the castle, permanent settlement based on buildings that continue in use, and . . . the presence of craftsmen.”3 Permanence, diversification, organization, and community—these are key words and ideas that distinguish the village from more fleeting and less purposeful agricultural settlements.

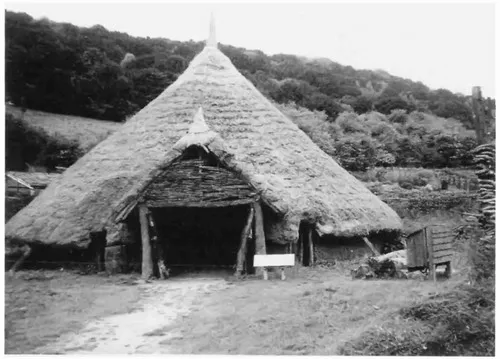

Archeology has uncovered the sites of many prehistoric settlements in Northern Europe and the British Isles. Relics of the Bronze Age (roughly 3000 B.C. to 600 B.C.) include the remains of stone-walled enclosures surrounding clusters of huts. From the Iron Age (600 B.C. to the first century A.D.), circles of postholes mark the places where stood houses and sheds. Stones and ditches define the fields. Here we can first detect the presence of a “field system,” a historic advance over the old “slash and burn” agriculture that cleared, cultivated, then abandoned and moved on. The fields, delineated by their borders or barriers, were cultivated in a recognized pattern of crops and possibly fallow.4 The so-called Celtic fields, irregular squares of often less than an acre, were cultivated with the ard, a sharpened bough of wood with an iron tip, drawn by one or two oxen, which scratched the surface of light soil enough to allow sowing. Other Iron Age tools included hoes, small sickles, and spades. The rotary quern or hand mill (a disklike upper stone turning around a central spindle over a stationary lower stone) was used to grind grain. Crops included different kinds of wheat (spelt, emmer), barley, rye, oats, vetch, hay, flax, and dye-stuffs. Livestock were cattle, pigs, sheep, horses, domestic fowl, and honeybees.5

Circle of megaliths at Avebury (Wiltshire), relic of Neolithic Britain.

Reconstruction of Iron Age house on site of settlement of c. 300 B.C., Butser Ancient Farm Project, Petersfield (Hampshire).

A rare glimpse of Iron Age agriculture comes from the Roman historian Tacitus, who in his Germania (A.D. 98) describes a farming society primitive by Roman standards:

Scratch plow, without coulter or mouldboard, from the Utrecht Psalter (c. A.D. 830). British Library, Harley Ms. 603, f. 54v.

Land [is divided] among them according to rank; the division is facilitated by the wide tracts of fields available. These plowlands are changed yearly and still there is more than enough . . . Although their land is fertile and extensive, they fail to take full advantage of it by planting orchards, fencing off meadows, or irrigating gardens; the only demand they make upon the soil is to produce a grain crop. Hence even the year itself is not divided by them into as many seasons as with us: winter, spring, and summer they understand and have names for; the name of autumn is as completely unknown to them as are the good things that it can bring.

Tacitus seems to be describing a kind of field system with communal control by a tribe or clan. The context, however, makes it clear that he is not talking about a system centered on a permanent village:

The peoples of Germany never live in cities and will not even have their houses adjoining. They dwell apart, scattered here and there, wherever a spring, field, or grove takes their fancy. Their settlements (vici) are not laid out in our style, with buildings adjacent and connected . . . They do not . . . make use of masonry or tiles; for all purposes they employ rough-hewn timber . . . Some parts, however, they carefully smear over with clay . . . They also dig underground caves, which they cover with piles of manure and use both as refuges from the winter and as storehouses for produce.6

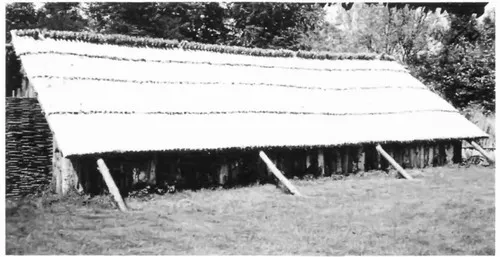

Tacitus here is referring to the two main house types that dominated the landscape into the early Middle Ages. The first was the timber-framed building, which might, as in his account, be covered with clay, usually smeared over a framework of branches (wattle and daub), its most frequent design type the longhouse or byre-house, with animals at one end and people at the other, often with no separation but a manure trench. The second was the sunken hut or grubenhaus, dug into the soil to the depth of half a yard to a yard, with an area of five to ten square yards, and used alternatively for people, animals, storage, or workshop.

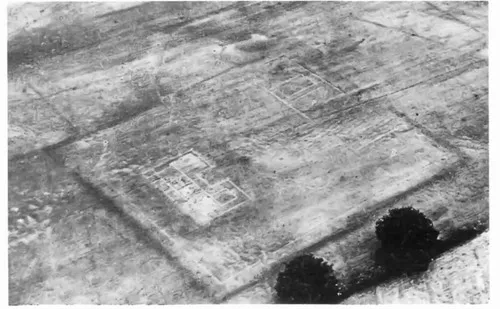

The Roman occupation of Gaul, beginning in the first century B.C., and of Britain, starting a century later, introduced two types of rural community to northwest Europe. The first was the slave-manned villa, a plantation of 450 to 600 acres centered on a lord’s residence built in stone. The second was similar, but worked by peasants, or serfs, who cultivated their own plots of land and also that of their lord.7 To the native Iron Age crops of wheat, barley, flax, and vetch, the Romans added peas, turnips, parsnips, cabbages, and other vegetables, along with fruits and the grape.8 Plows were improved by the addition of iron coulters (vertical knife-blades in front of the plowshare), and wooden mouldboards, which turned the soil and made superfluous the cross-plowing (crisscrossing at right angles) formerly practiced. Large sickles and scythes were added to the Iron Age stock of tools.9

Reconstruction of Iron Age longhouse (c. A.D. 60) at Iceni Village, Cockley Cley (Norfolk).

The Romans introduced not only a craftsman’s but an engineer’s approach to farming: wells, irrigation systems, the scientific application of fertilizer, even consideration of the effect of prevailing winds on structures. The number of sheep and horses increased significantly.10 The Romans did not, however, work any revolution in basic agricultural methods, and the true village remained conspicuous by its absence. In Britain, in Gaul, and indeed throughout the Empire, the population dwelt in cities, on plantations, or dispersed in tiny hamlets and isolated homesteads.

Sometimes small pioneering groups of settlers entered an area, exploited it for a time, then moved on, whether because of deficient farming techniques, a fall in population, military insecurity, or a combination of the three. Archeology has explored a settlement at Wijster, in the Netherlands, dating from about A.D. 150, the site of four isolated farmsteads, with seven buildings, four large houses and three smaller ones. In another century, it grew to nineteen large and seven small buildings; by the middle of the fifth century, to thirty-five large and fourteen small buildings in an organized plan defined by a network of roads. Wijster had, in fact, many of the qualifications of a true village, but not permanence. At the end of the fifth century, it was abandoned. Another site was Feddersen Wierde, on the North Sea, in the first century B.C., the setting of a small group of farms. In the first century A.D. the inhabitants built an artificial mound to protect themselves against a rise in water; by the third century there were thirty-nine houses, one of them possibly that of a lord. In the fifth century it was abandoned. Similar proto-villages have been unearthed in England and on the Continent dating on into the ninth century.11

The countryside of Western Europe remained, in the words of Chapelot and Fossier, “ill-defined, full of shadows and contrasts, isolated and unorganized islands of cultivation, patches of uncertain authority, scattered family groupings around a patriarch, a chieftain, or a rich man . . . a landscape still in a state of anarchy, in short, the picture of a world that man seemed unable to control or dominate.”12 Population density was only two to five persons per square kilometer in Britain, as in Germany, somewhat higher in France.13 Land was plentiful, people scarce.

Foundation lines of walled Roman villa at Ditchley (Oxfordshire), with field boundaries and cropmarks. Ashmolean Museum.

In the tenth century the first villages destined to endure appeared in Europe. They were “nucleated”—that is, they were clusters of dwellings surrounded by areas of cultivation. Their appearance coincided with the developing seigneurial system, the establishment of estates held by powerful local lords.

In the Mediterranean area the village typically clustered around a castle, on a hilltop, surrounded by its own wall, with fields, vineyards, and animal enclosures in the plain below. In contrast, the prototype of the village of northwest Europe and England centered around the church and the manor house, and was sited where water was available from springs or streams.14 The houses, straggling in all directions, were dominated by the two ancient types described by Tacitus, the longhouse and the sunken hut. Each occupied a small plot bounded by hedges, fences, or ditches. Most of the village land lay outside, however, including not only the cultivated fields but the meadow, marsh, and forest. In the organization of cropping and grazing of these surrounding fields, and in the relations that consequently developed among the villagers and between the villagers and their lord, lay a major historical development.

Crop ro...