- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

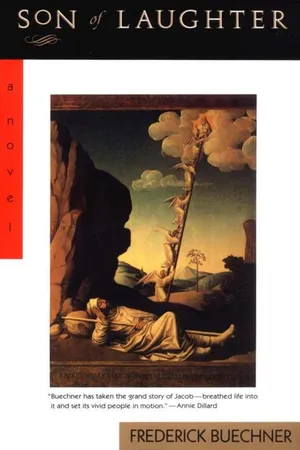

The Son of Laughter

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Son of Laughter by Frederick Buechner in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9780061752520ONE

THE PROMISING

1

THE BURIED GODS

THEY ALL HAD NAMES, but I have forgotten them. One name sounded like a man hocking up a bone. Another went lu lu like a man with a woman under him. Another rattled like the god of a tree. One name was so tiny and dry you hardly dared speak it for fear it would crumble to dust on your lips. They were no taller than from my wrist to the tip of my middle finger. They lived on a shelf in my uncle’s cellar. My uncle was Laban. The cellar walls were of earth. It was always black down there even when the sun was high.

One of them was a bearded child in a high peaked cap. Another wore a skirt of fish scales with plump toes and a round, full belly. Another was bald and beardless. He held his member out before him in both hands. He had no eyes and only a crack in the stone for his mouth. They told my uncle many things that he lusted to know. They told him where to look for the missing goat or the strayed lamb. They told him when to plant and where in the city of Haran to buy for least and sell for most. They told him about rain. I have seen him come lurching up the ladder so drunk on their secrets that his eyes were rolling around in his head and his jaw hanging.

He kept a lamp burning down there for them at all hours. He fed them on barley cakes, honey cakes, radishes, beer. He rubbed them with oil—their beards and bellies, their fat toes. He burned things for them. Every day he talked to them. You could hear him at it. He wheedled and bullied and teased the way he traded oxen. My uncle was an ox himself. His neck was as thick as his head was wide. He said it would come in handy if they ever tried hanging him. His face was the color of brick. He always put his arm around your shoulder when he was talking to you or patted your cheek with his hand. “As long as we love each other, darling,” he would say. “That’s all that matters.” His other hand was probably in your pocket.

After twenty years, we finally left him. I waited till he was off at a shearing so he wouldn’t know. There were enough of us by then to stretch as far as the eye could see—my wives and the children, the servants, beasts, baggage, tenting, everything we could carry with us. We also carried with us my uncle’s gods with their large members and fish-scale skirts though I didn’t know it at the time. It was of all people my timid-hearted wife, Rachel, his daughter, who thought of taking them. She dreaded what might happen to us on our long journey, and she was afraid of what my brother might do when the two of us came face to face again after so many years. She was afraid he might kill me. He had good cause. She believed the gods would keep us safe. So she stole the whole pack of them and had them stowed in a sack which she kept close by her both waking and sleeping.

We had been traveling some days when my uncle returned from his flocks to find us gone. He overtook us just as we were making camp among high, wooded hills. His face was streaming with tears.

How could I leave him without so much as saying good-bye? How could I cheat him of the chance to throw one last great feast in my honor with music and dancing? How could I rob him of his daughters and his grandchildren, the only comfort he had now that old age was upon him? He wailed and thumped his chest. His small eyes were pink with grief and fierce reproach.

Worst of all, he said, how could I steal his gods? I did not know yet that Rachel had stolen them.

I said if he could find them, he was welcome to them. I swore I would have whoever took them killed on the spot. So he rushed like a madman from tent to tent searching till he came to Rachel’s tent. She had just time to sit down on the sack and spread her skirts over it before he entered. She asked his pardon for not rising to greet him, that gentle, courteous woman. It was her time for bleeding, she said. She meant him to believe it was the unclean blood a woman sheds by being a woman, and so he believed. The truth was otherwise. She bled indeed, but it was the stone gods she sat on in their sack that bloodied her with their pointed caps and sharp edges. Her flesh was white and soft as cheese where they wounded her. Her father leaned over and kissed her brow for the pain he saw in it, little guessing what it was that pained her. You could tell he was full of shame at having suspected her of thieving. Even the gods must have been moved by the tenderness of the scene.

It wasn’t long afterward, when Laban had gone, that I got rid of them. It was for the Fear’s sake I did it. The Fear came to me in the night and whispered words of hope into my ear. He told me that he loved me as he had loved Laughter, my father, before me and Abraham, my grandfather, before that. He repeated the ancient promises that never fail to frighten me with their beauty just as the Fear himself never fails to frighten me. So when the time was ripe, I did it. We were in Shechem, where two of my sons had brought terrible shame upon us.

I had a pit dug under an oak tree that stood so tall and reached out so far with its crooked arms that no other tree dared grow near it. I told my people to place their gods in the pit. They thought I had lost my wits, but they didn’t dare defy me so far from home. I stood by the raw grave and watched as one by one each father among them came up and threw into it the gods he had fed and worshiped all his life and his father before him.

Some of the gods were stone like my uncle’s. Others were painted wood, or bone, or baked clay. Some were stuck all over with feathers. Some were shriveled and black as carrion. When the men were finished, I added my uncle’s gods to the heap. I added the silver god that was mine. Then I told every last man and woman of them to throw their earrings in on top of them. I threw my own earrings in on top of them. I hoped the gods might find all that treasure some consolation for being treated so shabbily.

They are there in the earth to this day as far as I know. They and the earrings are all tumbled together in the dark. The earth stops their eyes and fills their mouths. The god of the oak fetters them with roots stronger even than they are strong.

When I say that I have forgotten their names, I mean that I cannot remember their names without trying. There are also times when I cannot forget their names without trying.

Maybe they also remember me. Who knows about gods? Maybe they have seen every step I have taken ever since. Maybe they are still waiting for me to call once again on their queer and terrible names.

2

THE RAM IN THE THICKET

THE WATER IN THE BOTTOM of a well looks far away and black. Sometimes there is a star in it. My father’s eyes were like that—black, liquid, faraway eyes. My father’s name was Isaac, which means Laughter. Abraham named him Laughter because on the day that the strangers told him that his wife Sarah was going to bear him a son when she was an old woman, he fell on his face laughing, and in the door of the tent Sarah almost laughed herself into a fit as well.

Sometimes there was a star in Laughter’s eyes. He was a slow-moving, heavy-set man, heavy on his feet and heavy-limbed. He had no hair on his head, and his mottled scalp was shiny as polished stone. When he talked to you, he tilted his head to one side as if he admired you so much that he couldn’t bear to look at you straight on. He gave you a sad little smile. He made you feel he was holding great strength in check out of deference to you.

There was never a more deferential man than Laughter when things were going well with him, which they rarely did. He could suit even his shape to your whim. If he felt that his presence was becoming distasteful to you for some reason, he could hunch, shrug, shrivel himself to a size no bigger than a child’s. If he wanted to be warm and welcoming, he could make it so that you had to flatten yourself against the wall to leave room for him.

When he spoke to his friends, of which he did not have many, it was less like speaking than crooning. He tuned his voice to be so easy on your ears that you might not hear it at all if you happened to be thinking of something else. Even when you did hear it, he said what he said in such a sidelong way, took such pains never to press his point home, that you often didn’t have any idea what he has talking about.

When I was a boy, he sometimes talked to me about his father—Abraham, the father of fathers, the Fear’s friend. Abraham was a barrel-chested old man with a beard dyed crimson and the hooded eyes of the desert. He had a habit, when he spoke, of putting his hands on your shoulders and of drawing you gradually closer and closer as the words flowed until at the end his great nostrils were almost in your face like twin entrances to a cave. He was rich in herds and flocks, not to mention also in silver and gold, in tents and in women. He was the bane of many small kings and in many ways was more of a king than any of them. It is said that Abraham talked with the Fear the way a man talks to his friend. He would argue with him. They say that sometimes he would even nag him into changing his mind. Perhaps that was why my grandfather was the one whom the Fear chose out of all men on earth to breed a lucky people who would someday bring luck to the whole world.

All that and more was my grandfather Abraham, yet sadness always rose in me when my father talked about him. I pictured him laboring under his wealth and his honors like an ass under three hundred weight of millet. I pictured his eyes red and bleary from years of whipping sand. I pictured him breaking wind, groaning, as he heaved himself out of the pit of sleep at sundown to lead his precious train of kin, beasts, baggage, mile after moonlit mile in search of pasturage and whatever else he spent his days in search of. I saw him as a homesick, sore-footed man. A wanderer. A broken heart.

I remember Laughter lying on his back once on a pile of rugs with one arm over his head and the hand spread out on his naked scalp like a crab. You could hear the wind whistling through the tent ropes outside. The flap was open so the thin smoke of the burning dung could escape. He was speaking slowly and to no particular end as far as I could see. I was only half listening. Then little by little it began to dawn on me that for once he was telling me a story about Abraham that I had never heard before.

“You know what killed my mother, don’t you?” Laughter said. His mother was my grandmother Sarah. “Of course you don’t know what killed her. How could you know when I have never told you? I will not tell you now either. I will leave it to you to decide for yourself what killed her. You are old enough to figure it out. Figuring out will make you older still. My mother was herself very old by then. Something else would have killed her soon enough if this thing hadn’t, but it was this thing that killed her. You will understand it for yourself if you have any sense at all.”

He was not crooning now. His words fell heavy and dense like cow dung. First a heap, then another heap.

“Your grandfather told two of his men to saddle one of the best she-asses,” Laughter said. “The beast was white as milk. She was doe-eyed and gentle. Her belly was soft as a girl’s. There was no need to bridle her. You could tell her with your knees whatever you wanted her to do. She was so light on her feet they called her Swallow. He had them girth her up with the saddle he had used at his wedding. It was of braided hides, fringed, with a pommel of goat’s horn and teak. He said the two men were to come with him. He said I was to come with him. He told me he was going into the hills to make a gift to the Fear. The Fear had told him he would welcome a gift. He had me help the men cut the sticks, three large bundles of them, one for each of our backs. He said we were to find green sticks as well as dry ones because he would need much smoke to float his gift to the sky. He said he would ride Swallow with provisions enough for a three-day journey, and the men and I would walk behind. It was summer, but over his tunic he wore a mantle of henna wool that my mother had embroidered for him with vine leaves. Around his neck he wore the collar of jasper and topaz that I had never seen him wear before except when he was meeting in full council with the fathers or palavering with kings. He daubed holy signs on his cheeks and forehead with wood ash so that he would be acceptable in the Fear’s sight when he approached him. He wrapped his face in the folds of his headcloth so the holiness would not be soiled by the eyes of strangers.”

Laughter groaned and rolled over on his back. He placed his hands side by side on his face to cover his eyes. The tip of his nose jutted up between them. For a while he breathed so slowly and heavily I thought he had fallen asleep.

He said, “We reached the place on the third day. It was high in the hills. There was an outcropping of rock overlooking the valley. He told the men to stay below with Swallow. He made me carry all three bundles of sticks behind him. He carried a live coal in a cup. I had to stop several times as we climbed. He could hear it when I stopped and would wait for me. He never looked around at me. He never spoke.”

Rebekah, my mother, came in about then and interrupted Laughter. She was a short woman with a large mane of curly hair. She did not dress or bind it then like other women, and her little face was almost lost in the midst of it. She had puffy cheeks and large front teeth that made her look like a coney peering out of a bush. Laughter raised one hand from his eyes to see who it was. He replaced it when he saw.

“Please go away,” he said. “I am talking to my son.”

“It is high time,” she said. “It is your other son you are usually talking to.”

“They are twins,” he said. “It makes no difference which one I talk to.”

“It makes a difference to them,” she said. “It makes a difference to the one you never talk to.”

She said to me, “Why don’t you speak up for yourself? Tell him how it feels to have a father who never talks to you.”

“I am talking to him now,” Laughter said. “Would you please go away?”

“You are talking to him now because you are ashamed of the way you have always treated him. You have good reason to feel shame. Just because he is quiet and stays at home doing what he is supposed to do, you treat him like dung under your feet. His brother is your heart’s treasure because he is always off killing things for you to eat. You will know who to thank for it when you eat yourself into an early grave.”

Laughter remained silent a long time after my mother left. He stared up at the lamp hanging over him. There were bats shuffling and creaking in the tamarisk outside. They were getting ready to fly out for the evening’s forage. Finally he rolled over on one elbow to face me. He rested his cheek on the palm of his hand. It pushed his mouth crooked. He continued his story.

“My father, Abraham, carried the live coal in the cup,” he said. “He also carried his knife. But he did not carry any gift as far as I could see. It seemed a queer thing to be going to the Fear empty-handed, and I think I asked him about it. I don’t remember how he answered me. It has been many years. I was only a boy. I thought no more about it. I thought only that my father must know what he was doing. I was right. He knew what he was doing.”

Laughter said, “Heels.”

He sometimes called me Heels, which is the meaning of Jacob, because I was born on the heels of my twin. They say I tried to beat him out of the womb by grabbing his heels from behind, but I failed. He was the first of us to come out of the womb. Our father called him Esau, which means hairy. He was hairy all over. I was as bare as an egg.

Laughter said, “Heels, I am telling this to you, not to your brother.” It was one of the times there was a star in his black, faraway eyes. “I know which of you is good at which things and which of you is good at other things, whatever your mother says. I praise the Fear day and night for both of my sons.”

“Thank you,” I said.

“Now I will finish my story,” Laughter said. He started to weep.

It was the worst moment of my life up till then. I was so ashamed of Laughter’s weeping that I thought I was going to be sick. I wanted to run out of the tent so I would not have to see his tears. Instead I stayed in the tent to punish him by seeing them. I stayed in the tent to punish myself by seeing them. It was slovenly, shameful weeping. Dribble ran out of Laughter’s nose. His mouth ran spittle. He bared his gums in an ugly, comic way. He blubbered like a woman. His whole thick frame shook. I squatted by the smoking dung staring at him.

Sometimes he would pause in the middle of his story to utter broken bits of prayer to the Fear. Sometimes his words stopped altogether, and he waved his hands and made terrible faces instead. Once or twice he trie...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Part One

- Part Two

- About the Author

- Other Books by Dana Cameron

- Copyright

- About the Publisher