![]()

Part 1: Entangled Legacies of Extreme Violence: Traumatic Memories in the Aftermath of the Yugoslav Successor Wars

![]()

Antje Postema

“Read and Remember”: Ozren Kebo’s Sarajevo for Beginners as Ironic Guidebook and Narrative Memorial

Introduction

This essay examines Ozren Kebo’s Sarajevo for Beginners [Sarajevo za početnike], a collection of short prose written and published during the war in Bosnia. Kebo’s text fits with other works of Bosnian literature that serve as witnesses to the trauma of Sarajevo’s three-and-a-half-year besiegement; it also shares features with contemporary acts of memorialization, and in particular the literary memorialization, that took place both during and following the war. Kebo’s title highlights the work’s particular take on the relationship between narrative documentation and memorialization. It overtly addresses the novice reader as a “beginner” or “dummy” in need of a guide to the city during its wartime perils. However, the seeming straightforwardness of the project’s paratextual framing -its relationship between narrator and reader, and between literature and traumatic experience – is meaningfully complicated by the tone, the fragmentary nature, and the lived experience to which the work refers. In the following pages, I demonstrate, first of all, that the textual features employed in Sarajevo for Beginners allow it to fit into a number of overlapping genres: in addition to being a book for beginners, it can also be read as a field and survival guide. These heavily stylized genres are all characterized by an eminently practical relationship between text and experience; moreover, they are fundamentally fragmentary rather than exhaustive. While delineating the varied generic contours of the work, I argue that the kinds of textual practice that Kebo employs in Sarajevo for Beginners function ironically; they allow the narrative to address critically the experiential traumas the prose incorporates and to reflexively evaluate the dialectical relationship between textual structures and the acts of memorialization in which they participate.

Kebo is a Bosnian journalist and author who spent most of his adult life living and working in Sarajevo.4 As a journalist and editor, he has been heavily involved in Sarajevo’s dynamic and celebrated cultural scene that defined the urban landscape and made the city rightfully famous from the early 1980s onward.5 During the war, this cultural activity was marshaled for anti-war movements and channeled into a huge number and variety of “cultural resistance” projects.6 The proximal impetus behind and constant referential focus of Kebo’s collection is the traumatic experience of the war, which he personally witnessed. Sarajevo for Beginners belongs among the numerous contemporary artistic projects that both protested the bitter violence raging in Bosnia and viewed artistic media as crucial to both intellectual engagement with the circumstances of war and as a way to preserve highly valued aspects of prewar life in Sarajevo.7 These works of wartime Bosnian literary witness are, by and large, marked by a sense of immediacy towards unfolding events. They are frequently gritty, sometimes crude. They were published amid wartime shortages and distributed with great difficulty and often with authorial sacrifice. They are politically and ethically engaged. Many are difficult to fit into strict genres and often push at the boundary separating fiction from non-fiction. They are intertextually rich and employ a wide variety of media (often within a single work). They are compact and their elements are often short and fragmentary.8

Indeed, it is this fragmentariness that I wish to focus on as a way of introducing Sarajevo for Beginners. During the war, many of the most influential literary works were published serially in journals and magazines, often in several different versions.9 Their components – often short stories, essays, or poems -were characterized by brevity, urgency, aphorism, and a narrow subjective rather than totalizing perspective. We can read such literary productions as directly emerging out of circumstance; wartime privations often complicated and inhibited the physical act of writing, and, as Judith Herman maintains, “people who have survived atrocities often tell their stories in a highly emotional, contradictory, and fragmented manner” (Herman 1992, 1). Instead of foregrounding such an interpretation, I focus here on how the fragmentary qualities of Sarajevo for Beginners exist in a dialectical relationship with traumatic experience; the work’s textuality is influenced by atrocity, violence, and death, but it also pointedly responds to circumstance. Here I employ a notion of fragments similar to that of Camelia Elias, who views the fragment as a performative textual act that is “habitually defined, not as an object in itself, but in relation to notions of either the period or aesthetics/genre in which it appears” (Elias 2004, 4). In this, the choice of the fragment form becomes both a generic as well as a critical – even polemical – gesture.

Wartime narratives like Sarajevo for Beginners often took the form of fragments in scope and organization. By focusing on the physical city, which is broken into pieces, authors find a narrative correlation in the fragmentary form: notions of “part” and “whole” link the experience of destruction and its narration. Beyond merely using the fragment as a form, however, these wartime works self-reflexively argue for the fragment as a truthful or adequate way to express the experience of war. This move towards the fragment in its ethical as well as aesthetic dimensions can be seen as an explicit rejection of postmodernist textual practices, which were often avoided by wartime Bosnian authors who critiqued postmodernism largely for what they saw as its lack of ethical concern. Instead, these authors seemed to hold to the inverse of Adorno’s famous maxim, that “Das Ganze ist das Unwahre [the whole is the untrue]” (Adorno 2005, 50), employing the fragment in ways that metatextually allied it with a truth value.

In addition to its fragmentary quality, Sarajevo for Beginners shares with a number of wartime volumes a highly developed and effectively deployed sense of irony. In approaching and delineating the function and import of irony in Kebo’s volume, I rely on Linda Hutcheon’s seminal study on the discursive contexts, political entanglement, and ethical stakes of irony. As she maintains, “irony is a ‘weighted’ mode of discourse in the sense that it is asymmetrical, unbalanced in favor of the silent and the unsaid […]. [It] involves the attribution of an evaluative, even judgmental attitude” (Hutcheon 1995, 35). For this reason, and because it relies on relationality, inclusivity, and differentiality (Hutcheon 1995, 56-57), an ironic text can be dexterously employed to bring textuality and social reality into the same critical sphere. As Hutcheon notes, “[u]nlike metaphor or allegory, which demand similar supplementing of meaning, irony has an evaluative edge and manages to provoke emotional responses in those who ‘get’ it and those who don’t, as well as in its targets and in what some people call its ‘victims’” (Hutcheon 1995, 2). The omnipresence of irony in Sarajevo for Beginners gives it its characteristic and, moreover, generative “edginess.”

My major argument rests on the fact that just as traumatic circumstance interacts with textual practice in Sarajevo for Beginners as a work of witness literature, so too are its textual features implicated in conceptions of memory and, more specifically, commemorative practices. As Geoffrey Hartman argues, “memory, and especially the memory that goes into storytelling, is not simply an afterbirth of experience, a secondary formation: it enables experiencing” (Hartman 1996,158). Here, it is crucial to keep in mind Astrid Erll’s explication of how literature functions as a medium of cultural memory (Erll 2011). Beyond the intertextual mechanisms by which literary texts recall and memorialize (Lachmann 1997), I am here particularly concerned with the notion of memory’s mediation through specific generic or rhetorical practices. Such mediation is indicative of the way in which memory is “stabilized” through narrative symbolization (Assmann 2003). Literary texts take particular genres and styles; they might represent the past in experiential, monumental, antagonistic, historicizing, or reflexive modes (Erll 2011, 158). The medial frameworks used in recounting or engaging with the past constitute not only modes of narration but also, equally and inseparably, “modes of remembering” (Erll 2008a, 7; 2008b). Mnemonic and commemorative practices in culture influence the possibilities for literary representations and vice versa. On the one hand, a work can be, in Erll’s terms, “memory-reflexive” insofar as it uses the concepts of memory as a narrative theme or trope, metatextually contemplates the structure and function of memory, and demonstrates the mediation involved in representing memory. On the other hand, a work can be “memory-productive” to the extent that it employs powerful images and tropes about the past. Memory-productive works do not necessarily address the concept of memory but can shape and disseminate representations of the past that are incorporated into and shape collective memories (Erll 2011, 137-151). Sarajevo for Beginners is both memory-reflexive and memory-productive because it both explicitly comments on the work of memory in wartime and employs powerful images that resonate with wider commemorative activity in Bosnia during and after the war. The interwoven expectations developed by both literary genre and memorial culture motivate my investigation of Kebo’s collection. Moreover, the particular contours of genre and memorialization found in Sarajevo for Beginners support my argument that the book exists in a dynamic relationship with larger strategies that commemorate the siege of Sarajevo.

A beginner’s guide to besieged Sarajevo

As is immediately apparent, Kebo’s title highlights a particular approach to the relationship between narrative documentation and memorialization. Printed on its first page or above the column (depending on the version), the title strongly influences the way readers encounter it, the presuppositions they entertain, and the web of associations (both textual and supra-textual) into which they immediately fit the work. The words “Sarajevo for beginners” thus function as a paratext (Genette 1997).10 In this case, a seemingly clear and delimited title presents the work to its reading public, fitting the reader, the narrator, and the body of the text into a set of interacting relationships. The implied naive reader is thus someone unfamiliar with Sarajevo during wartime, to whom Kebo’s expert narrator addresses Sarajevo for Beginners in the form of a guide. Despite a title that paratextually circumscribes how the reader approaches the text, Sarajevo for Beginners does not neatly fit into a genre category. The book productively exploits the resulting mismatch between genre expectations and textual execution. Indeed, it is primarily in this gap between what is promised and what is deliver ed, what is expected and what can be achieved, that the book enacts its particular type of commemorative practice.

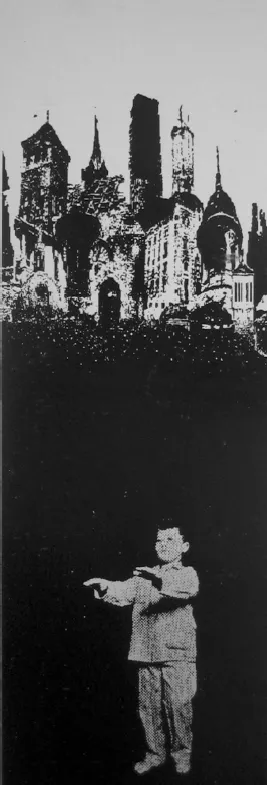

Sarajevo for Beginners was first published serially in the well-known monthly cultural-political journal, BH Dani, its two columns of text separated on the page by a striking collage.11 The bottom of this composite image depicts the young sleepwalker, Malik, from Emir Kusturica’s hugely popular film, When Father was Away on Business [Otac na službenom putu] (1985). The image’s top section features a horizontally compressed version of the poster, “Sarajevo 1992: Summer,” by the graphic arts group, TRIO; the TRIO poster is itself a photographic collage of buildings in Sarajevo’s war-torn skyline (Fig.1). The choice of images is intertextually and critically evocative – either image, by itself, would have been immediately recognizable to readers of BH Dani in 1994 and would have elicited a number of associations and highly-charged emotions.

The image of Malik functions as a metonym for Kusturica’s film, which thematizes the turbulent socio-political climate in Yugoslavia following Tito’s 1948 break with Stalin. The film is focalized through the young Malik, who remains largely unaware of the political causes and ramifications of his father’s imprisonment. The magical realism of Malik’s sleepwalking becomes a metaphor for a naive, and slightly victimized, perspective on reality.

Kusturica’s film was known, loved, and celebrated at home and abroad.12 However, at the time Sarajevo for Beginners appeared in BH Dani, controversy raged about Kusturica himself, who had moved abroad during the war (to the United States, France, and more problematically, Serbia).13 Through statements he made in the local and international press, Kusturica had distanced himself from Sarajevo society and openly critiqued former colleagues. In the opinion of many in Bosnia and abroad, including many actors and artists who had contributed to When Father was Away on Business and who continued to live and work in besieged Sarajevo, Kusturica had turned his back on his native city.14 An image of Malik, therefore, metonymically recalls the figure of Kusturica him self, functioning as an antagonistic mnemonic device that both criticizes the film director and sets the stage for Kebo’s text as a whole.

Fig. 1: Collage accompanying Sarajevo for Beginners columns in BH Dani (1994). Top: TRIO “Sarajevo 1992: Summer” (poster).

Bottom: Malik sleepwalking (film poster for Emir Kusturica’s When Father Was Away on Business [1985]). Used with permission.

The Sarajevo skyline at the top of the collage, meanwhile, refers to the entire oeuvre of postcard-sized prints produced by the TRIO graphic design group. TRIO, a collaboration of the artists Delila Hadžihalilović, Bojan Hadžihalilović, and Lela Mulabegović, were active since the 1980s but rose to particular prominence during the war. Building on its pre-war pop-art aesthetic, Trio’s wartime works pointedly critiqued society and politics with wry black humor. TRIO relied on the appropriation of well-known international images and slogans, altering the meaning of these by situating them in the new context of wartime Sarajevo – and thereby commenting on the war. TRIO’s use of pop-art as an aesthetic medium can be seen in their use of advertising (which integrates “low-cultural” elements into the typically “el...