Ohio Short Histories of Africa

This series of Ohio Short Histories of Africa is meant for those who are looking for a brief but lively introduction to a wide range of topics in African history, politics, and biography, written by some of the leading experts in their fields.

Steve Biko

by Lindy Wilson

ISBN: 978-0-8214-2025-6

e-ISBN: 978-0-8214-4441-2

Spear of the Nation (Umkhonto weSizwe): South Africa’s Liberation Army, 1960s–1990s

by Janet Cherry

ISBN: 978-0-8214-2026-3

e-ISBN: 978-0-8214-4443-6

Epidemics: The Story of South Africa’s Five Most Lethal Human Diseases

by Howard Phillips

ISBN: 978-0-8214-2028-7

e-ISBN: 978-0-8214-4442-9

South Africa’s Struggle for Human Rights

by Saul Dubow

ISBN: 978-0-8214-2027-0

e-ISBN: 978-0-8214-4440-5

San Rock Art

by J.D. Lewis-Williams

ISBN: 978-0-8214-2045-4

e-ISBN: 978-0-8214-4458-0

Ingrid Jonker: Poet under Apartheid

by Louise Viljoen

ISBN: 978-0-8214-2048-5

e-ISBN: 978-0-8214-4460-3

The ANC Youth League

by Clive Glaser

ISBN: 978-0-8214-2044-7

e-ISBN: 978-0-8214-4457-3

Govan Mbeki

by Colin Bundy

ISBN: 978-0-8214-2046-1

e-ISBN: 978-0-8214-4459-7

The Idea of the ANC

by Anthony Butler

ISBN: 978-0-8214-2053-9

e-ISBN: 978-0-8214-4463-4

Emperor Haile Selassie

by Bereket Habte Selassie

ISBN: 978-0-8214-2127-7

e-ISBN: 978-0-8214-4508-2

Thomas Sankara: An African Revolutionary

by Ernest Harsch

ISBN: 978-0-8214-2126-0

e-ISBN: 978-0-8214-4507-5

Patrice Lumumba

by Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja

ISBN: 978-0-8214-2125-3

e-ISBN: 978-0-8214-4506-8

Thomas Sankara

An African Revolutionary

Ernest Harsch

Ohio University Press

Athens

Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 45701

ohioswallow.com

© 2014 by Ohio University Press

All rights reserved

To obtain permission to quote, reprint, or otherwise reproduce or distribute material from Ohio University Press publications, please contact our rights and permissions department at (740) 593-1154 or (740) 593-4536 (fax).

Printed in the United States of America

Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper ƒ ™

24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Harsch, Ernest, author.

Thomas Sankara : an African revolutionary / Ernest Harsch.

pages cm. — (Ohio short histories of Africa)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8214-2126-0 (pb : alk. paper) —ISBN 978-0-8214-4507-5 (pdf)

1. Sankara, Thomas. 2. Presidents—Burkina Faso—Biography. 3. Burkina Faso—Politics and government—1960–1987. I. Title. II. Series: Ohio short histories of Africa.

DT555.83.S36H37 2014

966.25052—dc23

2014029649

Cover design by Joey Hi-Fi

Preface

Writing this short account of the life of Thomas Sankara required making a number of choices and judgment calls. Given space limitations, which aspects to explore in some detail, which to touch only lightly? Although Sankara was a complex, multisided individual, he was above all a political actor. So the focus here is on his political views and undertakings, especially during his four years as president.

I knew Sankara. I spoke with him directly on half a dozen occasions, a couple times at length. I was also able to observe him giving public addresses and in other interactions while I was covering developments in Burkina Faso as a journalist. This limited familiarity has led me to highlight certain aspects of his personality and style. It may as well introduce some subjective bias. I do not apologize for my sympathies, but simply wish to alert the reader that my interpretations may differ from those of scholars who were less favorable to Sankara’s revolutionary outlook. At the same time, I take note of certain shortcomings of his time in office that some of those who idolize him might prefer to pass over.

Sankara clearly played a leading, even preponderant role in his country’s revolutionary process, but it was nevertheless a collective enterprise. It had many other actors, both in the leadership and on the ground. Their contributions cannot be given their due attention in a biography such as this, which necessarily focuses on an individual. Nor is it possible to assess Sankara’s precise role and influence with full certainty. Some initiatives obviously were his own. Yet his convictions led him to work through collective leadership bodies, making it hard to pinpoint precisely how his views and actions shaped developments. Accounts by some of his contemporaries have helped shed patches of light on these questions. I hope that future scholarship will illuminate yet more.

In my research on this period in the history of Burkina Faso, I am indebted to a number of individuals. Some of those I interviewed are cited in the bibliography. In particular, I would like to thank Paul Sankara for his personal observations about his brother, and Madnodje Mounoubai for sharing several anecdotes about his time working with Sankara. Others living within Burkina Faso or outside the country also provided insights, but I will refrain from thanking them by name.

Among scholars, Bruno Jaffré has conducted the most detailed research into Sankara’s life, and his Biographie de Thomas Sankara was invaluable in the writing of chapters 2 and 3 in particular. I thank him for reviewing this book’s manuscript and making several useful observations. I also appreciate Eloise Linger’s sharp editorial eye, as well as the comments and suggestions of the publisher’s two anonymous reviewers.

To date, the most comprehensive source for Sankara’s own words is the collection published by Pathfinder Press, Thomas Sankara Speaks: The Burkina Faso Revolution, 1983–87, available in both English and French editions. The reader interested in more than the short passages from Sankara used in this biography is directed to that collection. I am grateful to the publisher for permission to use its English translations of the quotations drawn from it. For the many quotations taken from other sources, the translations from the original French are my own.

1: “Another Way of Governing”

The women had traveled from across Burkina Faso, packing the tiered seats and spilling into the aisles of the central auditorium of the House of the People in Ouagadougou. There were more than three thousand of them, young and old, a few with babies on their laps, most dressed in multicolored traditional fabrics, often in the red, white, and dark blue pattern of the Women’s Union of Burkina. They had come to the capital to celebrate their day—March 8, International Women’s Day—with speeches, slogans, stories, songs, and dance. They cheered and chanted with leaders of the women’s union, who spoke sometimes in French and sometimes in Mooré, Jula, or Fulfuldé, three of the country’s indigenous languages.

That day in 1987 they also came to hear their energetic young president, Thomas Sankara, who had already initiated numerous measures to improve women’s standing and opportunities. Sankara’s speech did not disappoint. He had made some of the main points before: that women had to organize, that traditional customs had to shed their oppressive features, that social inequality had to be combated, and that the revolution would triumph only if women became full participants. But this time he also anchored his arguments to an exhaustive review of women’s oppression through eight millennia of social evolution and gave numerous examples of its signs in contemporary Burkinabè society, sometimes in poetic flights of oratory. He scathingly criticized Burkinabè men—including some among his fellow revolutionaries—who hampered advancement for the women in their own families. Transformation would be incomplete, he said, if “the new kind of woman must live with the old kind of man,” drawing much applause and laughter.

Sankara’s interaction with the women that day was not unusual. Since becoming president in August 1983 at the head of a revolutionary alliance of young radical military officers and civilian political activists, he had repeatedly traveled across the country to outline his government’s ambitious initiatives and projects. On his tours he met with villagers, youth leaders, elders, artisans, farmers, and other citizens. He addressed enthusiastic audiences. Many listeners knew that his words were not just the promises of another politician or government official. They had already seen tangible improvements in their own towns and villages: new schools, health clinics, sports fields, water reservoirs, and irrigation dams. People were impressed by the uncharacteristic vigor of this leader, who was not only impatient to battle poverty but also quick to jail bureaucrats caught stealing from the meager public treasury. Some certainly were alarmed by the revolutionaries’ rhetoric about class struggle and calls to crush those who opposed the government. Yet Sankara himself demonstrated a particular ability to convey his sweeping vision of societal transformation in concrete terms and actions that could be readily appreciated by ordinary people and by reformers across ideological boundaries. Until he was cut down in a military coup in October 1987, Sankara was widely seen as having done more to stimulate economic, social, and political progress than any previous leader.

Sankara left a mark beyond his own country. During visits elsewhere in Africa or at international summit meetings, his speeches struck listeners with their forcefulness and clarity. His frank criticisms of the policies of some of the world’s most powerful nations were all the more notable coming from a representative of a small, poor, landlocked state that few had previously heard of.

The French authorities had heard of it, at least by the name Haute-Volta (Upper Volta), as they called the territory they had colonized and ruled from 1896 to 1960. When President François Mitterrand visited Ouagadougou in November 1986, he encountered a changed country, with a different kind of leader. President Sankara greeted his guest not with the usual diplomatic niceties and ceremonial toasts. He offered a “duel” of ideas and oratory. Sankara began with a plea for the rights of the Palestinian people; defended Nicaragua, then under attack by US-backed “contras”; and scolded Paris for its policies in Africa and toward African immigrants in France. Recalling the spirit of the French revolution of 1789, he said his government would be willing to sign a military pact with France if that would bring to Burkina Faso shipments of arms that he could then send onward to liberation forces fighting the apartheid regime in South Africa. If Sankara’s verbal jousts took Mitterrand off guard, the French president recovered quickly. He set aside his prepared remarks and took on Sankara point by point. He also praised the Burkinabè president’s directness and the seriousness of his questions. With Sankara, Mitterrand said, “it is not easy to sleep peacefully” or to maintain a calm conscience. Half jokingly, he added, “This is a somewhat troublesome man, President Sankara!”

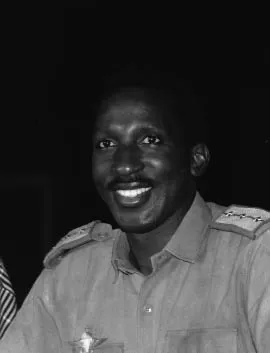

Thomas Sankara (1949–1987). Credit: Ernest Harsch

It was not only the Sankara government’s daring foreign policy positions that resonated across Africa. People...