![]()

PART I

Paths to a West African Past

![]()

1

The Holocene Prehistory of West Africa

10,000–1000 BP

SUSAN KEECH McINTOSH

Introduction

Over the past thirty years, most archaeological research in West Africa has focused on the record of human activities since 10,000 BP.1 Although the coverage is spotty and huge areas remain inadequately understood and documented, this research has transformed earlier notions of a West African past that was largely static until stimulus or intervention from the north transformed Iron Age societies. Furthermore, the sequences of change through time that this research documents indicate some unexpected and possibly unique historical trajectories.

Current evidence suggests that West African food production was indigenous and followed a different pattern from the familiar sequences of the temperate Old World (the Near East, Europe, and China) in which domesticated plants were an important element of the earliest food-producing economies. The earliest food-producing economies in West Africa were pastoral, based on cattle that were domesticated indigenously in northeast Africa, it appears, several millennia before the first domesticated plants appear in the archaeological record.

As archaeological research has shifted from a focus on isolated single sites, where data from one excavation were extrapolated and assumed to apply to a broad set of sites with nominally similar material culture, to the investigation of many sites within a region, our understanding of the complexity and diversity of the West African past has grown. In the temperate Old World, economic specialization, an early sign of growing social complexity, most frequently involved craft activities; in West Africa, an equally important aspect was subsistence specialization. By 4000 BP when the earliest documented domestic plants appeared, there was a concomitant development of specialized fishing economies that probably interacted with food-producing economies within the same region by means of subsistence exchange, creating a complex web of interdependent communities.

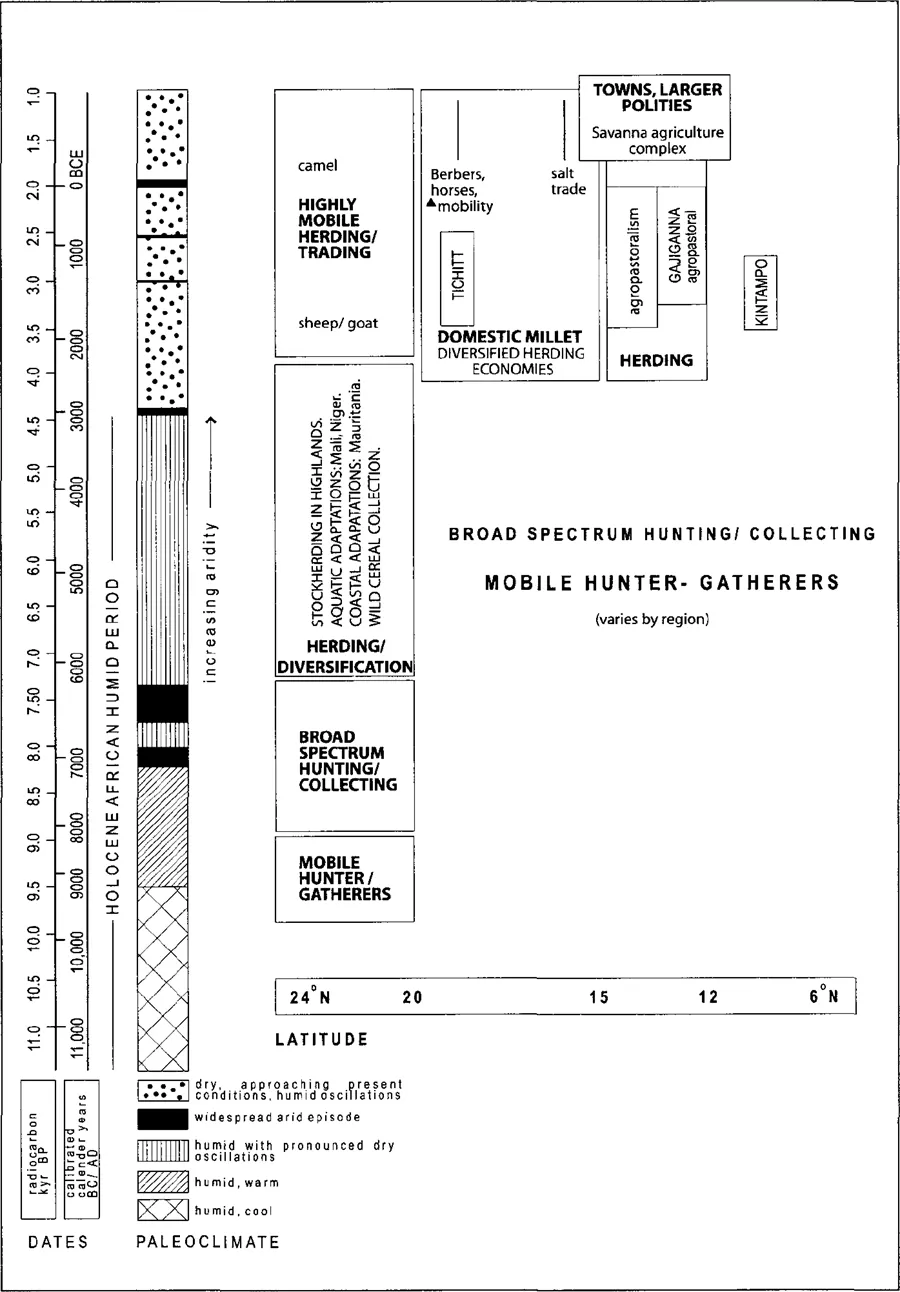

Fig. 1.1 Table showing major economic changes in West Africa, along with recognized archaeological traditions, arranged by latitude against changing climate trends through the Holocene.

Upon the important bases of cattle (with varying percentages of sheep and goats), domestic cereals (millet, rice) from 4000 BP, and ecologically based subsistence exchange, complex societies emerged in favored locales in West Africa. These were areas of low rainfall (where the tsetse fly that carried sleeping sickness so frequently fatal to cattle and humans could not thrive) and abundant water. The Middle Niger floodplain, where the Niger flows north through arid grass- and scrubland thereby seasonally flooding the vast flat expanse of the Inland Niger delta, is one such locale. Here, the domestication of African rice reduced population mobility to the extent that settlement mounds began to form in the floodplain. From investigation of these highly visible sites in various regions of the Middle Niger, we can begin to trace the emergence of extensive multi-settlement systems and their increase in scale and complexity.

Urban thresholds were reached at Jenne-jeno by 800 CE, and may have been reached earlier at Ja, the source of Jenne’s founding population, according to oral tradition. Undoubtedly, in the vast, undocumented regions elsewhere in West Africa, similar transformations occurred. Much research remains to be done, but enough has been accomplished to make it clear that many earlier assumptions about the trajectory of West Africa’s past were wrong.

The Pleistocene/Holocene transition

There is abundant evidence for human occupation in West Africa during the Pleistocene (1.7 million years to 10,000 years ago). The discovery of hominid fossils in the Lake Chad Basin confirms that hominids were present in West Africa much earlier, extending back as far as six or seven million years ago. Unlike East Africa, however, the record of hominid fossils and undisturbed archaeological sites is extremely sparse. Fossil discoveries depend on two geological processes: sedimentation to preserve and fossilize the skeleton after death, and exposure of the ancient fossil-bearing sediments through tectonic uplift, erosion, or both. Much of West Africa is relatively flat and geologically ancient. There is little topographic variation south of the Sahara to generate robust sedimentation, and even less recent faulting and uplift. Therefore, discovery of hominid fossils will probably remain a rare event. Many of the more recent Pleistocene deposits containing not just fossils, but artifactual evidence of human activities, have long ago been scoured away and reworked by water and wind. Sometimes, the artifacts have been transported to new locations by rapidly moving water and redeposited. Surface materials of the Lower Paleolithic/Early Stone Age (chopper tools, ‘Acheulian’ hand axes and cleavers) are especially common north of 16° N latitude. Middle Stone Age artifacts (a variety of flake and core industries dating presumptively to 120,000-20,000 BP) are also quite widespread, but rarely found in primary contexts (i.e., original contexts of use and deposition). For these reasons, our discussion focuses on the last 10,000 years, for which evidence of human society and activity can be found in its original context.

Fig. 1.2 West Africa: natural features and regions

(Source: based on map p.27, The Atlas of Africa, Règine Van Chi-Bonnardel, New York: Free Press, 1973, editions ‘Jeune Afrique’)

The end of the Pleistocene involved a dramatic change in vegetation communities and their distribution in West Africa. For much of the last glacial maximum 20,000-14,000 BP, West Africa was exceptionally dry and substantially cooler. The desert margin lay 500 km south of its present position. Equatorial forest was restricted to a few refuge areas along the southern coast. Small bands of hunter-gatherers were sparsely distributed in the south. Approximately 12,500 years ago (10,500 BP) the rapid onset of much wetter conditions transformed the landscape of West Africa. The humid forest zone expanded 350 km north of its present limits, and the desert effectively disappeared from West Africa. Closed lake basins all over northern West Africa reached Holocene high stands between 9500 and 8500 BP. Lake Chad, for example, became Megachad, over fifteen times its present size and 40 m deeper. The Sahara became a land of lakes, grassy plains, and forested uplands.

The fauna of northern Mali, Mauritania and Niger included elephant, giraffe, hippo, crocodile, and Nile perch plus many varieties of catfish. Hunter-gatherers expanded into this newly verdant zone. In the Aïr Mountains of Niger, hunters seasonally occupied base camps in the mountains as well as specialized, hunting/processing sites on lakeshores in the adjacent lowlands. Armed with small blades, geometric microliths, and a variety of arrow points, these groups hunted wild buffalo, antelope and gazelle, and also fished. By the tenth millennium BP, Saharan groups were making pottery, among the earliest anywhere in the world. After 9000 BP, grinding stones became common at northern sites, indicating intensive processing of plant foods, especially wild cereals.

What accounted for such a rapid change in climate? Climate in West Africa is proximally produced by the seasonal migration and pulsation of two air masses — the dry tropical and the humid maritime continental masses. Where these air masses meet and interact (a front known as the Intertropical Convergence Zone — ITCZ) monsoonal rainfall occurs.2 The ICTZ annual migration cycle proceeds from the desert margin in the north to the equatorial forest in the south, producing ever more prodigious rains as it moves southwards, and these are repeated as the ITCZ moves northwards again. To the north, the dry season between the two passages of the ITCZ is nine to eleven months long. The migration of the ITCZ, along with the relatively flat topography of West Africa, produces the familiar West African latitudinal zoning of vegetation, from equatorial forest to Guinean forest and savanna, to dry, Sudanic savanna, sahel and desert. The zones shift latitudinally in response to the changes in the displacement of the ITCZ migration. During the early Holocene, the northern front of the ITCZ was displaced 500-700 km or more northwards.

This dramatic shift in vegetation zones and water budget was only one — although certainly the most extensive — of many changes in climate during the Holocene in West Africa. Some of these lasted for hundreds of years and were pan-African or even global in scale. Others were shorter and more regional or local in effect. Many variables could affect climate and mediate how its effects were experienced locally. Unlike in temperate zones, where temperature is the major factor affecting the rhythm of the seasons, moisture dictates the pattern of growth cycles in the tropics. Particularly in the sahel and dry savanna zones, even minor shifts in the availability of water can have major effects on human societies. During the Holocene, human groups faced the challenge of climatic oscillations occurring on scales ranging from millennia to decades.

Human response to this challenge involved interaction between the physical world of plants, animals, soils and climate and the human domain of culture, experience and action. The African milieu has been characterized as hostile, with its inhabitants engaged in continual struggle. Some suggest that African innovation in the face of the challenge was infinite. This probably overstates the case. The West African environment posed constraints on innovation; one finite subset of responses was more viable than another. At the same time, what was a disaster to one group was a potential opportunity to another. The farmer, the fisher and the nomad view the world very differently! All, however, developed strategies to address effectively an environment where moisture fluctuations represent substantial risks to life and health. Looking across the Holocene, we can see several recurring patterns in the response of West African societies to risk over time: mobility, which kept population densities generally low (aided by disease vectors) and labor at a premium; and exchange and alliances across ecological boundaries.

The Holocene Humid Period and the appearance of cattle herding

The early Holocene Humid Period that began 11,000 years ago was punctuated by at least one abrupt, widespread desiccation phase between 8000 and 7000 BP. Soon after this, pottery-using pastoralist groups with domestic cattle and some sheep and goats became widespread in West Africa between 20 and 24° N. They exploited wild plants, and also hunted and fished to varying degrees. Analysis of cattle DNA indicates that indigenous, wild African cattle were domesticated as early as 9000 years ago in northern Africa. Dung, dried plant fodder, and the bones of Barbary sheep (Ammotragus lervia) dating between 9000 and 8000 BP in caves in the Acacus highlands of Libya indicate that hunter-collectors were penning and controlling these animals. These behaviors did not, however, lead to domestication, defined as genetic changes indicating dependence on humans. The only domesticated caprines documented in Africa were sheep and goat introduced from the Near East 7000-8000 years ago.

Ammotragus is but one of the 86 species of artiodactyls (grazing animals with an even number of functional toes) in Africa that were not domesticated. What accounts for the successful domestication of cattle alone among this rich diversity of ungulates? Wild cattle had a package of characteristics that made them particularly suited for control by humans: they live in herds with a hierarchical social structure (the human herder usurped the role of the lead male), are relatively slow and easy to pen without inducing panic and shock, and will tolerate being penned with individuals from different herds. Human cultural preference and behavior probably also played a role. Fiona Marshall has suggested that wild cattle may have initially been brought under control in order to assure predictable access to meat for important rituals and feast occasions, when gifts of meat were essential. This would have been of particular concern during dry periods, when grazing prey became more mobile. Although we commonly think of domestication as producing a more abu...