![]()

CHAPTER 1

Traditional Arabian Agriculture

ALTHOUGH SAND and camels dominate most people’s impressions of the Arabian Peninsula, agriculture has been practiced in Arabia for over five thousand years, and Arabian farmers have traditionally been quite adept in creating microclimates of luxuriant growth in an unforgiving landscape. These pockets of agricultural fertility, however, have tended to be scattered and infrequent in a landscape characterized by overall sterility. The transition between the barren desert and agricultural fecundity, in fact, could be quite dramatic. For example, when Lieutenant Wellsted of the Indian Navy entered the oasis of Minna in December 1835, he found to his surprise fields green with grain and sugarcane, hedged in by “the lofty almond, citron, and orange-trees, yielding a delicious fragrance on each hand . . . streams of water, flowing in all directions intersected our path.” “Is this Arabia,” he asked his companions, “this country that we have looked on heretofore as a desert?”1 As we shall see throughout this book, the abrupt environmental transition between the dry desert on one hand and the humid fertility of the palm oases and wadi drainage channels on the other has played a crucial role in influencing the origins, distribution, and scale of African labor in traditional Arabian agriculture.

Four agricultural techniques dominated traditional Arabian agricultural production, each tied to a different hydrological regime. In a few parts of the Arabian Peninsula, especially in the Yemen and ‘Asir highlands, dry (rain-fed) agriculture was possible, mainly with the assistance of agricultural terraces. Farmers also captured rainfall for agricultural production by harnessing occasional floodwaters by means of dikes, dams, and irrigation channels. Groundwater, in turn, was captured in two main ways. High mountain groundwaters could be tapped using qanat artificial springs, also called “chains of wells,” to divert the water from plentiful mountain aquifers and transport it to agricultural fields, which in some cases lay many kilometers distant. Finally, groundwater could be harnessed almost everywhere using the jalib, or draw well, a ubiquitous feature of traditional Arabian agriculture. In the sections below, I will discuss each of these techniques in turn—partially for their own sake, but also because these techniques provide the necessary context by which to understand the roles played by slavery and malaria in traditional Arabian agriculture.

Origins of Arabian Peninsula Agriculture

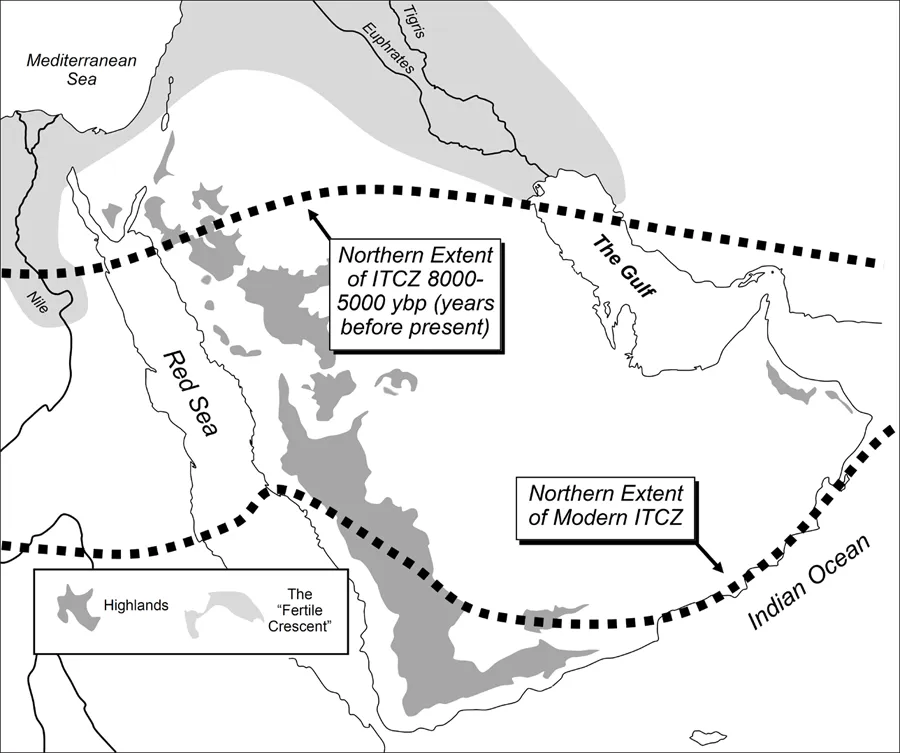

One of the ironies of the history of the Arabian Peninsula is that, despite its close proximity to the early centers of agriculture in the so-called “Fertile Crescent” of the Levant, Egypt, and Iraq, the Arabian Peninsula was a relatively late adopter of agriculture. This was not due to lack of water resources. Quite the contrary: during the period up until 3000 BCE, the Arabian Peninsula was considerably wetter than it is today, since the ITCZ (Intertropical Convergence Zone), which marks the northern limits of the Indian Ocean monsoon, then penetrated as far north as Sinai and southern Iraq. At that time, most of the Arabian Peninsula’s landscape was capable of supporting “comparatively lush vegetation,” and would have greatly resembled the modern African savannah, with a mixture of grasslands, scattered medium-sized trees, and shallow, seasonal lakes.2 From the standpoint of agriculture, however, these ample monsoon rains were a hindrance rather than a help, as the early domesticates of the Fertile Crescent, such as wheat, emmer, and barley, had evolved to live in a Mediterranean weather regime of winter rains and summer drought, and thus had difficulty passing south of the monsoon line. The peoples of the Arabian Peninsula did adopt the domesticated animals of the Fertile Crescent, especially cattle, which became crucial to the economic, social, and religious life of the Peninsula.3 However, as Arabian archaeologist Joy McCorriston has noted, it would take nearly four thousand years before domesticated plants followed domesticated animals into the Arabian Peninsula.4 Map 1.1 shows the approximate location of the ITCZ both five thousand years ago and in the modern era.

Map 1.1. The ITCZ (Intertropical Convergence Zone), past and present

Source: Juris Zarins, “Environmental Disruption and Human Response: An Archaeological-Historical Example from South Arabia,” in Environmental Disaster and the Archeology of Human Response, edited by Garth Bawden and Richard Martin Reycraft, 35–49, Maxwell Museum of Anthropology Anthropological Papers 7 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2000).

In addition to serving as an effective rain barrier against Fertile Crescent grains, Arabia’s summer rainfall regime also inhibited the cultivation of the date palm, a plant that would become indispensable to Arabian agriculture. Date palms, which probably originated in southern Iraq, prefer wet winters and hot, dry summers. Not surprisingly, then, date palm cultivation in the Arabian Peninsula began only after 3000 BCE, when the ITCZ began to shift to its modern position at the southern heel of the Arabian Peninsula, bringing with it summer monsoon rains. The first evidence of date cultivation in the Arabian Peninsula comes from the Hili region in the modern-day United Arab Emirates, where both date stones and date wood were discovered in archaeological sites dating to between 3000 and 2000 BCE.5 Similar findings in Kuwait, Oman, and Bahrain suggest that the date palm entered Arabia via the Gulf during the third century BCE. From there, the date palm likely jumped from oasis to oasis in central and western Arabia, carried by farmers to the few areas of relatively high groundwater in the increasingly desiccated landscape.

Date palms were crucial to Arabian agriculture not only because they thrived in Arabia’s post–3000 BCE climate, but also because the palms themselves created microclimates of shade and humidity that were suitable to agricultural production. The extreme heat and aridity of the Arabian Peninsula was inimical to most of the cultivars of the Fertile Crescent, which could grow poorly if at all in Arabian soils. Palm trees, however, provided necessary protection from the omnipresent sun. The shade of the palms also protected soil moisture, and this moisture, combined with transpiration of water from the palms themselves, meant that the level of humidity within a palm plantation was significantly higher than in the surrounding desert. In the words of Lieutenant Wellsted,

the instant you step from the Desert within the Grove, a most sensible change of the atmosphere is experienced. The air feels cold and damp; the ground in every direction is saturated with moisture; and, from the density of the shade, the whole appears dark and gloomy.6

Wellsted confirmed this impression of a “sensible change” with instrument data. His thermometer indicated that the temperature inside the houses of the Omani oasis he was exploring was 55°F (12.8°C), while the temperature reading in the oasis 6 inches above the moist ground was only 45°F (7.2°C). Wellsted provided no temperature data from outside of the oasis, but the modern average temperature in Oman’s interior in December, the time when Wellsted was traveling, ranges between 62.6°F (17°C) and 73.4°F (23°C).

The cooler, moister atmosphere of the oases, as we shall see in greater detail in chapter 4, created near-perfect conditions for the breeding and proliferation of Anopheles mosquitoes, the insect vector of malaria. However, the microclimate under the palms was also highly suitable for agriculture, allowing the cultivation of numerous domesticated plants beneath the canopy of the palms that otherwise could not survive the rigors of the Arabian climate. Arabian traveler Harry St. John Bridger Philby described the fertility and the diversity of one such garden in the Najd oasis town of Hamar as follows:

The groves of the oasis are of very prosperous appearance containing a rich undergrowth of fruit-trees and vegetables—pomegranates . . . peaches, lemons, cotton-plants, a sort of scarlet-runner trained up the palm-trunks, egg-plants, and chilies.7

The same mixture of palms and understory plants was found throughout Arabia, though with a different mix of crops depending on the local climate. In the district of Aflaj in the south of Najd, Philby described the Laila oasis as hosting “lucerne [alfalfa], saffron, cotton-bushes along the borders, pomegranates, figs, and vines, in addition to several different varieties of date trees.”8 In the northern Najd town of Ha’il, crops grown under the palms included grains, pumpkins, millet, “different species of melons,” and “gourds of uncommonly large size.”9 In al-Hasa, springwater was so abundant that rice was sometimes cultivated in paddies built within the palm planations.10 The exact crops grown in any given region depended on the soil and climate, and probably varied seasonally according to rainfall and market prices. Nonetheless, the practice of combining palms with secondary crop cultivation was a constant throughout Arabia.

This form of farming, called bustan gardening in the literature (a redundancy, since bustan means garden in Arabic), is probably nearly as old as the cultivation of the date palm in the Arabian Peninsula. Such gardens consisted of a number of small fields, averaging about 2 acres in size, and connected to each other and to a water source by a network of irrigation channels. The most commonly used tool for weeding and turning the soil was the hoe, as these fields were, for the most part, too small to be worked efficiently with animal labor, and in any case, the ubiquity of irrigation channels would have left a plow team little room for maneuver. If plows were used, they tended to be ards or scratch-plows. Unlike European moldboard plows, which essentially flip deeper soil back to the surface in order to recover leached-out nutrients, ards kill weeds and aerate the soil without turning it over, thus preventing the loss of precious soil moisture. Other tools used included sickles and a variety of knives adapted to palm cultivation.11

The use of fertilizers was moderate and depended on local availability. Animal manure was usually scarce, since most Arabian oases contained a minimum of livestock due to a scarcity of fodder, but soil and dung was collected from livestock pens, and stubble from previous crops was turned back into the soil.12 In the al-Hasa area, according to Danish traveler Barclay Raunkiaer, “straw and withered palm leaves [were] burnt and their ashes [were] dug into the earth” to enrich the soil.13 In nearby Bahrain, farmers fertilized their palms with the fins of the awwal, a “species of ray fish . . . steeped in water till they are putrid.”14 Dutch traveler Daniel van der Meulen reported that bird guano, collected from offshore islands near British Somaliland, was used as fertilizer in tobacco fields in the 1930s in Hadramaut, and in 1934, Freya Stark claimed that dried sardines were employed as fertilizers in the same fields, but it is not clear whether these were recent innovations or long-standing local practices.15 Some Arabian farms were further fertilized by floodwater sediment, as we will discuss below.

Water

As suggested in the quotation by Wellsted above about the sharp transition from dusty desert to moist fertility, the limiting factor in Arabian agriculture was the availability of water. The Arabian Desert is essentially an extension of the Sahara into Asia, and, as in the Sahara, rainfall tends to be both scant and scattered. Only the southernmost heel of the Arabian Peninsula, which benefits from the Indian Ocean monsoon, receives enough yearly rainfall for dry (that is, nonirrigated) farming. The mountains of Oman receive a significant amount of rainfall as well, from a combination of monsoon rains, winter showers, and the occasional cyclone. As for the rest of the Peninsula, rainfall on average is less than 100 millimeters per year, far below the threshold of dry farming. As a result, pastoralism rather than agriculture is the most prevalent lifeway in the Arabian Peninsula, and the camel rather than the date is the most familiar product of the Arabian Desert.

As a result of the limitations imposed by Arabia’s hydrological regime, agriculture in the Arabian Peninsula was traditionally carried out on a very small scale, at least in comparison with Arabia’s neighbors. Map 1.2 shows the distribution of the date palm in the Middle East of the 1920s, at a time when modern agricultural techniques such as tube wells had not yet transformed the region’s landscape. As is clear from the map, Arabia was a bit player in the field of agri...