![]()

Part I

Food Security and Insecurity: Causes and Consequences

![]()

1

Food Security

Food security has been a centrepiece of food and agricultural policy discussion since the food crises of the 1970s, and it has risen to prominence since 2007 among national governments, multilateral and bilateral institutions, and non-governmental organisations following the recent food crisis.

No one really knows how many people are malnourished. The statistics most frequently cited are that of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), which measures ‘undernutrition’, with the most recent estimate, released on 14 October 2009, indicating that 1.02 billion people are hungry, 15 per cent of the estimated world population in that year of 6.8 billion. This represents a sizeable increase from its 2006 estimate of 854 million people. Almost all of the undernourished are in developing countries, in which about 11 million children under five die each year. Malnutrition and hunger-related diseases cause 60 per cent of these deaths (UNICEF 2007).

This chapter begins by defining food security and insecurity, and goes on to trace the evolution of these concepts since the 1970s. It provides some discussions on the costs of chronic food insecurity and malnutrition to individuals and nations. The chapter then examines the causes of food insecurity, both chronic and transitory, elaborating on the factors behind the repeated occurrences of transitory food insecurity. Finally, it is imperative to examine the key factors that caused the 1972–1973 food crises, and to consider whether the same factors have been operating since then, leading to the most recent crisis of 2007 and beyond.

WHAT IS FOOD SECURITY?

Concern with food insecurity can be traced back to the first-world food crisis of 1972–1974 and beyond that at least to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s ‘State of the Union Address’ on 6 January 1941, before the US entered the Second World War, in which he spoke of ‘four essential freedoms’: freedom of speech, freedom of faith, freedom from want, and freedom from fear (Rosenman, in Shaw 2007: 3).

In 1943, the FAO’s founding conference was organised to consider the goal of freedom from want in relation to food and agriculture. Freedom from want was defined then as ‘a secure, an adequate, and a suitable supply of food for every man’ (FAO, in Shaw 2007: 3).

The overall objective of the conference was to promote the idea of ensuring ‘an abundant supply of the right kinds of food for all mankind’, with a clear emphasis on nutritional standards as a guide for governmental agricultural and economic policies for improving the nutrition and health of the world’s population. The conference declaration also recognised the causes of hunger and proposed some solutions (Shaw 2007: 3):

• Poverty is the first cause of malnutrition and hunger;

• Increasing food production will ensure availability but nations have to provide the markets to absorb it, thus, an expansion of the world economy should provide the purchasing power needed to maintain an adequate diet for all. Clear emphasis is put on the need for opportunities to create jobs, enlarged industrial production, and the elimination of labour exploitation;

• With an increasing flow of trade within and between countries, better management of domestic and international investment and currencies, and sustained internal and international economic growth, the food which is produced can be made available to all people.

During 1973, the world witnessed the most publicised food crisis, triggered by rising oil prices and consequently increasing input prices for items such as fertiliser and transport costs, in addition to a bad harvest year in the former Soviet Union, China, and India (Mackie 1974). These combined with the gradually increasing demand to absorb worldwide grain reserves (Leathers and Foster 2004). In the face of this crisis, the FAO held an international conference in 1974 at which the ‘Universal Declaration on the Eradication of Hunger and Malnutrition’ ‘solemnly proclaimed’ that ‘every man, woman and child has the inalienable right to be free from hunger and malnutrition in order to develop fully and maintain their physical and mental faculties’. The Declaration recognised the role of governments, and urged the participants to work together for increased food production and a more equitable and efficient distribution of food between and within countries. It reiterated that ‘all countries, big and small, rich or poor, are equal. All countries have a full right to participate in decisions on the food problem’. It also provided a definition of a world food security system (UN 1975: 2):

The wellbeing of the peoples of the world largely depends on the adequate production and distribution of food as well as the establishment of a world food security system which would insure adequate availability of, and reasonable prices for, food at all times, irrespective of periodic fluctuations and vagaries of weather conditions, and free of political and economic pressures, and should thus facilitate, amongst other things, the development process of developing countries.

Despite this clear understanding of the complexity of the issue of food insecurity, the policy trends of the 1970s were largely concerned with ensuring national and global food supplies to satisfy the most urgent emergencies and needs in low-income food deficit countries. The annotated bibliography compiled by Maxwell and Frankenberger (1992) contains 200 items, which together trace the evolution of the concept of ‘food security’ from concern with national food stocks in the 1970s (declining food availability) to a preoccupation with individual entitlements in the 1980s, and to accountability failures, the failure of informal safety nets, food aid failure, and the political and economic priorities of countries in the 1990s (Devereux 2009).

Devereux and Maxwell (2001: 13–21), highlighted three paradigm shifts which followed global and local trends:

1. From global and national to household and the individual – adequate world supplies of basic foodstuffs to offset fluctuations in production and prices and satisfy growing demands (UN 1975) – seeing food supply as the problem.

2. From a ‘food first’ perspective to a livelihood perspective – food is one part of the jigsaw of secure and sustainable livelihoods; meeting food needs as far as possible given immediate and future livelihood needs – concerns the long-term environmental capacity to supply food and the institutional capacity to enable access to food.

3. From objective indicators (the conditions of deprivation) such as poverty being seen as the main cause of subjective perceptions (feelings of deprivation, lack of self-esteem and self respect) (Kabeer 1988; Chambers et al. 1989) to the ‘fear that there will not be enough to eat’ (Maxwell 2001: 13–27).

Interest among academics and policymakers in defining and refining the concept of food security is evident from the significant amount of literature devoted to providing definitions, indicators, and conceptual models to measure and determine households’ and individuals’ food security status. Maxwell and Frankenberger (1992) cited 30 definitions put forward from 1975 to 1991, which have either been influential in the literature or which summarise agency views. Among the most influential are: Siamwalla and Valdes (1980), the FAO (1983), and the World Bank (1985). Most writers agree with the general idea proposed by Reutlinger (1982; 1985), that food security is:

Access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life. Its essential elements are the availability [Supply] of food and the ability [Demand] to gain it.

The United Nations (UN 1993) added another dimension to the definition: ‘a household is food secure when it has access to the food needed for a healthy life for all its members, adequate in terms of quality, quantity, safety and cultural acceptability’. The 1996 World Food Summit adopted a still more complex definition, encompassing regional and global levels, and this definition was adapted by the FAO in 2001:

Food security, at the individual, household, national, regional and global levels [is achieved] when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.

Maxwell and Frankenberger (1992: 4) identify four core concepts, implicit in the notion of ‘secure access to enough food at all times’. These are: (1) sufficiency of food, defined mainly as the calories needed for an active, healthy life; (2) access to food, which is inclusive of both the supply side [availability] and the demand side [purchasing power]; (3) security, defined by the balance between vulnerability, risk, and insurance; and (4) time, since food insecurity can be chronic, transitory, or cyclical.

Hahn (2000: 2) introduced a new definition of ‘nutrition security’ at the Scientific Academies Summit in 1996: nutrition security is achieved if

every individual has the physical, economic and environmental access to a balanced diet that includes the necessary macro and micro nutrients and safe drinking water, sanitation, environmental hygiene, primary health care and education so as to lead a healthy and productive life.

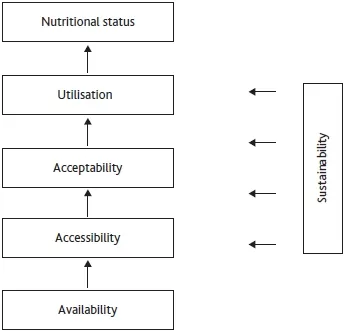

The following points sum up the meaning of the term, and the conditions that are essential to the attainment of ‘nutrition security’ at national and household levels (See Diagram 1.1):

• Food availability: refers to overall regional, national or even global food supply and shortfalls in supply compared to requirements (Hahn 2000: 2). It also means sufficient quantities of appropriate types of food from domestic production, commercial imports or food aid, which is consistently available to individuals or is within reasonable proximity to them or is within their reach (USAID 1992; 2006). However, providing a sufficient supply of food for all people at all times has historically been a major challenge. Institutional, technical, and scientific innovations have made important contributions in terms of quantity and economies of scale in the last 50 years but have fallen short of maintaining sustainability of production and access (Koc et al.: 2010).

• Access to food: refers to individuals with incomes or other resources that enable them to obtain appropriate levels of consumption of an adequate diet/nutrition level through purchase or barter; accessibility also deals with equality of access to food for every member of a household within and between regions. Inequities have resulted in serious entitlement shortfalls, reflecting class, gender, ethnic, racial, and age differentials, as well as national and regional gaps in development (ibid.).

• Cultural acceptability: the food system and practices of food distribution should reflect the social and cultural diversity of people, and this includes the suitability and acceptability of new scientific innovations to the social and ecological concerns of the nation in any given country (ibid.).

• Food utilisation: has a socioeconomic and biological aspect. It concerns a household’s decision making on the kind of food needed and how the food is allocated between the members of the household, in addition to the composition and the balance of the consumed food (carbohydrate, fat, protein, vitamins, and minerals). It also includes employing proper food processing, storage, provision, and the application of an adequate knowledge of nutrition and child-care techniques, along with adequate health and sanitation services (USAID 1992).

• Sustainability: is defined in terms of the adequacy of relevant measures to guarantee the sustainability of production, distribution, consumption, and waste management. A sustainable food system should help to satisfy current basic human needs, without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs. It must therefore maintain the ecological integrity of natural resources such as soil, water, fish stocks, forests, and overall biodiversity (ibid.).

WHAT IS FOOD INSECURITY?

Food insecurity is the lack of access to enough food; it can be chronic, and/or transitory and cyclical (World Bank, 1985: 1).

Chronic food insecurity is ‘a continuously inadequate diet caused by the inability to gain food’. It affects households that lack the ability either to buy enough food or to produce their own. Poverty is considered the root cause of chronic food insecurity (World Bank 1985: 1). Moreover, a continuously inadequate diet is synonymous with the term hunger or undernutrition, which is a medical term describing a situation of ‘stunting’ or stunted growth, resulting from food intake that is continuously insufficient to meet dietary energy requirements (FAO 2005a). This process starts in utero if the mother is malnourished, and continues until approximately the third year of the child’s life, leading to higher infant and child mortality. Once stunting has occurred, improved nutritional intake later in life cannot reverse the damage.

There are four types of malnutrition, according to Mayer (in Leathers and Foster 2004: 25). Firstly, over-nutrition occurs when a person consumes too many calories, and this is the most common nutritional problem in high-income countries and among high-income people in developing countries. The diet of the world’s high-income people usually consists of higher calories, saturated fats, salt, and sugar. Their diet-related illnesses include obesity, diabetes and hypertension.

Secondly, when a person has a condition or illness t...