![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Setting the Stage

This book is about farmer resistance to one particular genetic modification (Roundup resistance) in one particular crop (wheat). It is, therefore, essential to provide some background on Monsanto and its RR crops and to show the importance of wheat production and marketing to prairie agriculture. The farmers involved in the coalition to stop RR wheat came from various different organizations and worked alongside health and environmental groups. Each one of these organizations has a rich and complex history and politics that I can only briefly touch on in this book, but I do my best below to provide the reader with some context about the different organizations and their positions on RR wheat. In this opening chapter I also provide the reader with some details about my research methodology and lay out the theoretical concepts I believe are essential to understanding this book.

MONSANTO’S ROUNDUP READY

Roundup is the brand name of a broad-spectrum herbicide produced by Monsanto since 1974. Its active ingredient, glyphosate, is effective against a range of broadleaf and grass plants, including perennial weeds. Monsanto has always faced competition for this herbicide from companies like Bayer Crop Science, which produces a broad-spectrum herbicide called Liberty. Anticipating that the 2001 expiration of its Canadian patent on Roundup would bring greater competition, Monsanto began to experiment with genetic engineering. The company isolated a gene that is resistant to Roundup and began genetically engineering this gene into corn, cotton, soy, and canola seed. The first Roundup Ready crops became available for sale to North American farmers in the early 1990s. Because these crops are genetically engineered to be resistant to the Roundup herbicide, Monsanto now holds a new patent for the gene rather than the herbicide. A farmer must pay a per-acre fee and enter a legally binding technology use agreement in order to purchase and use Roundup Ready seed. Among other provisions, this controversial agreement prevents the farmer from saving seed for subsequent years and gives Monsanto licence to inspect and copy farm records and documents.

Monsanto is an American-based multinational corporation founded by John Queeny in 1901 in St. Louis, Missouri. The company produced saccharin (an artificial sweetener) for Coca-Cola and soon expanded to provide other industrial chemicals to various companies. By the 1960s, Monsanto was manufacturing several of its own widely-used and toxic chemicals, including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and Agent Orange, a defoliant used by the U.S. army in the Vietnam War. Although Monsanto was not the only producer of Agent Orange, its solution was found to have higher concentrations of dioxins than others, resulting in more devastating effects on humans.1 Monsanto also became an important promoter of plastics, Astroturf being its most successful product. In the 1980s, Monsanto started to shift its focus to biotechnologies and invested heavily in biotech research and development, becoming one of the first companies to do so. Around this time it bought up several seed companies from around the world. In 1996, the corporation split in two, spinning off its chemical operations into a new company called Solutia (which carries all liabilities associated with Monsanto’s industrial chemical past) and focussing its remaining operations around the life-science industry. It now boasts of being an agricultural company “invest[ing] almost $1.5 million a day to look for and bring to market the innovative technologies that our customers tell us make a difference on their farms.”2 The company now claims to be focussed in four main areas: genomics, biotech transformation, seed, and chemistry (centred on Roundup).

WHEAT PRODUCTION AND MARKETS

The possibility that Canada’s wheat markets could be jeopardized by the introduction of GM wheat in Canada became a crucial argument for the coalition against RR wheat. It is therefore important to present some data on the significance of wheat exports and the major importers of Canadian wheat. Much of the data below is focussed around the year 2001 to give a sense of wheat production and markets around the time that the coalition against GM wheat announced its opposition in July 2001. In Canada, the greatest area planted to wheat is found on the Canadian prairies, with smaller concentrations in southern and eastern Ontario (Figure 1). The arid land of the prairie provinces produces lower yields but higher protein content, a quality characteristic that is highly valued by flour millers.3 This inverse relationship between aridity and protein content creates the perplexing statistic that the provinces that grow the most wheat have the worst yield ratios (Figure 2).

The relatively high protein content of prairie wheat has been carefully marketed by the Canadian Wheat Board, which, until August 2012, was the monopoly marketing agency for the export of wheat and for domestic human consumption in the three prairie provinces and a small portion of British Columbia. While the rest of the data below is given for Canadian wheat, it provides a good representation of prairie wheat realities since the bulk of wheat in Canada is produced in the prairie provinces.

Figure 1. Wheat area distribution in Canada

Source: United States Department of Agriculture, Production Estimates and Crop Assessment Division of the Foreign Agricultural Service, with information based on data from the agricultural division of Statistics Canada, http://www.fas.usda.gov/remote/Canada/can_wha.htm.

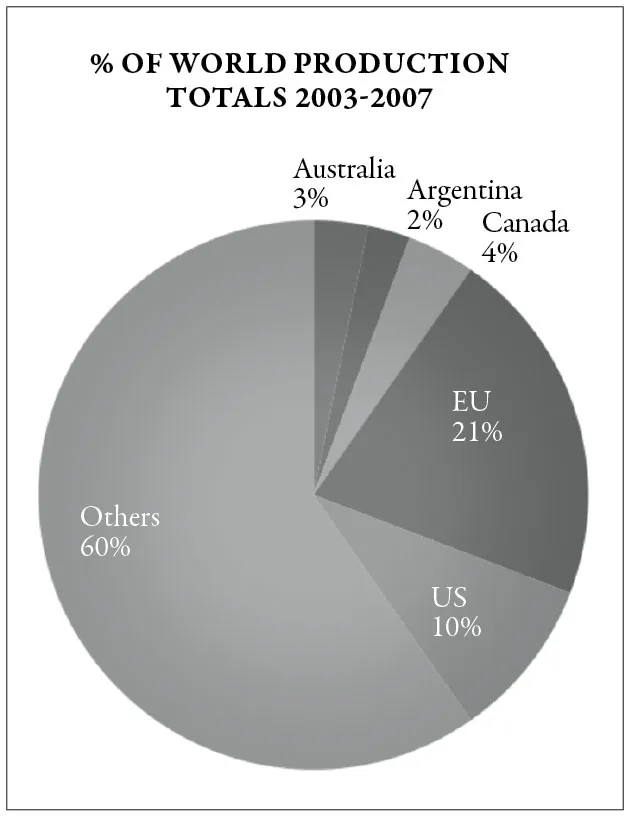

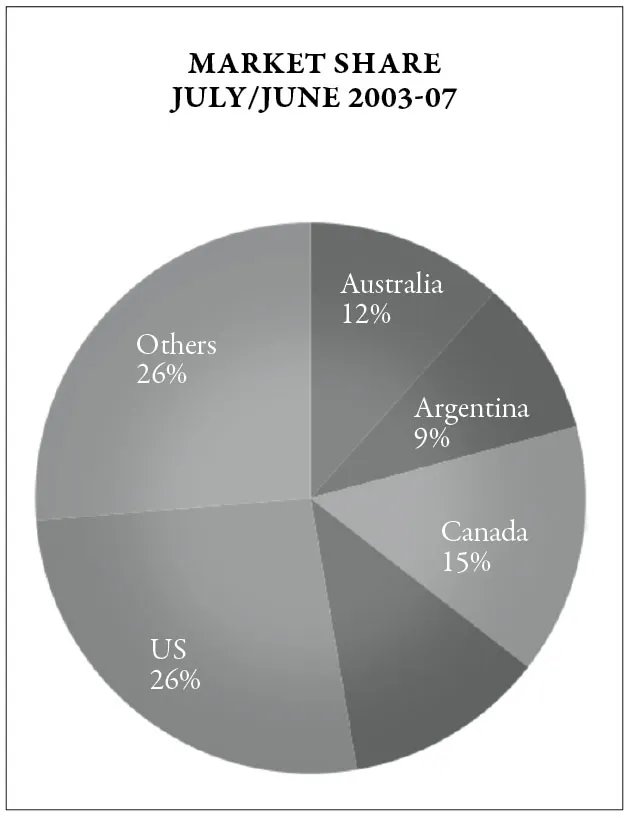

Canada is one of the world’s major producers, producing roughly 4 percent of the world’s wheat (Figure 3). This is significantly less than what is produced by the United States (roughly 10 percent) and by the EU as a whole (roughly 21 percent), but more than other major wheat producers like Argentina (2 percent) and Australia (3 percent). More significant is Canada’s 15 percent share of the world wheat trade (Figure 4). It is clear that wheat is important for Canada as an export crop; relatively little of its total production is reserved for domestic consumption.

As of the 2000–2001 crop year, and over the ten years ending in 2001, the five top importers of Canadian wheat were Japan, the U.S., Mexico, Iran, and China (Table 2). Significant to the story of GM wheat was Japan’s importance as an importer of Canadian wheat. Losing Japan as an export market for wheat because of its rejection of genetic modification could have been devastating for the wheat industry. Western Europe was another region that threatened to reject GM wheat, and while it accounted for only 8.8 percent of Canadian wheat exports in the 2001–2002 crop year (Table 3), it tended to buy high-quality, high-priced wheat and had been a key importing region since Canada began exporting wheat in the mid-nineteenth century. Figure 5 gives the total monetary value of Canadian wheat exports from 1998 to 2008, averaging $3.84 billion over that period.

Figure 2. Average wheat production by province, 1997-2001

Source: United States Department of Agriculture, Production Estimates and Crop Assessment Division of the Foreign Agricultural Service, with information based on data from the agricultural division of Statistics Canada, http://www.fas.usda.gov/remote/Canada/can_wha.htm.

Figure 3. Major wheat producers

Figure 4. World wheat trade

Source: Canadian Wheat Board, 2007–08 Annual Report, http://www.cwb.ca/public/en/about/investor/annual/pdf/07-08/2007-08_annual-report.pdf (accessed October 2008).

METHODOLOGICAL APPROACHES

I began my research on the politics of GM wheat on the Canadian prairies more than two full years after Monsanto had discontinued its breeding and field research on Roundup Ready wheat in Canada and the United States. Having followed the politics around RR wheat’s introduction through the media for the preceding five years and having read what academics had said about Canadian biotech policy and regulation, I had not thought twice about using words like “politics” and “struggle” when presenting my research interests to potential participants. The initial interviewees for this research embraced these terms and set out to convince me of their positions of opposition. It seemed natural to begin my interviews with representatives from the organizations that were formal members of the coalition against RR wheat that announced itself at a press conference in Winnipeg in July of 2001. From these interviews, and from an examination of all articles pertaining to genetic modification in Western Canada’s most prominent weekly farm newspaper from 2000 to 2006, I learned that a number of other actors were essential to the story of RR wheat. I expanded my field of research to include interviews with actors from all sides of the debate, including plant breeders, scientists, biotech lobby groups, industry organizations, the Canadian Biotechnology Advisory Committee, a representative from Monsanto, a representative from Saskatchewan Agriculture and Food, and farm organizations that publically supported the introduction of RR wheat.

The farm organizations involved in the coalition against RR wheat comprised the vast majority of farm groups on the prairies. The Wild Rose Agricultural Producers (WRAP), the general farm organization from Alberta, was notably absent from the coalition, since its equivalents in the two other prairie provinces were quite actively involved.4 The Saskatchewan general farm organization, the Agricultural Producers Association of Saskatchewan (APAS), is a newer organization (founded in 1999) and has been somewhat less stable than its Manitoban counterpart, the Keystone Agricultural Producers (KAP). While membership figures for farm organizations are generally not available and not released to the public, these farm organizations likely represent the largest number of farmers in their provinces. The National Farmers Union (NFU) represents fewer farmers, but has been a long-standing and outspoken feature of agricultural politics since its founding in 1969, and before that through its predecessors—first the United Farmers of Canada and then provincial farmers’ unions. Thus, the NFU has roots in the radical populist organizing of the first half of the twentieth century that resulted in cooperative grain elevators, political alliances with labour, and pools for wheat. The Canadian Wheat Board (CWB), which played a central role in the coalition, was one of the products of this early organizing and was supported by the vast majority of the farming population. In recent years, it has been marred by controversy over its monopoly and governance and was eventually dismantled on 1 August 2012 through an act of Parliament.5 Finally, the Saskatchewan Organic Directorate (SOD) is a relatively new group (founded in 1998) that has an increasing membership due to the growth of organic farming in Saskatchewan. Despite representing a minority of producers, it has received much media attention (because of its pursuit of a class action against Monsanto and Bayer for the contamination caused by GM canola) and recognition and support from the provincial government.

Table 1. Organizations involved in the 31 Ju...