![]()

Part 1

Vision: The Circle of Civilized Conditions

![]()

The Tuition of Thomas Moore

1

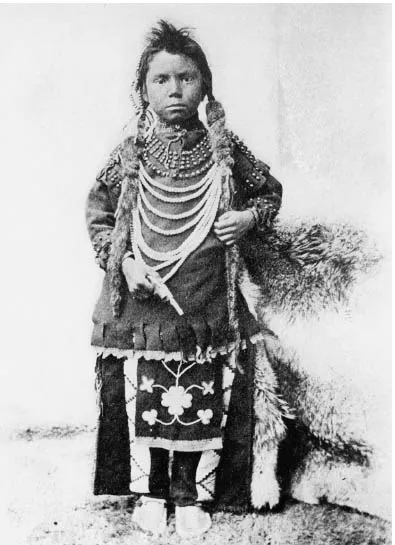

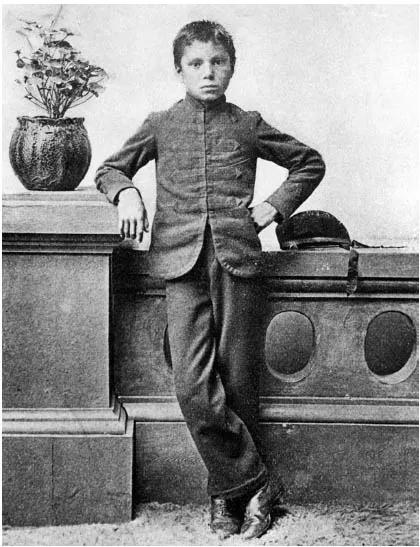

In its Annual Report of 1904, the Department of Indian Affairs published the photographs of the young Thomas Moore of the Regina Industrial School, “before and after tuition.” The images are a cogent expression of what federal policy had been since Confederation and what it would remain for many decades. It was a policy of assimilation, a policy designed to move Aboriginal communities from their “savage” state to that of “civilization” and thus to make in Canada but one community – a non-Aboriginal one.1

At the core of the policy was education. It was, according to Deputy Superintendent Duncan Campbell Scott, who steered the administration of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932, “by far the most important of the many subdivisions of the most complicated Indian problem.”2 In the education of the young lay the most potent power to effect cultural change – a power to be channelled through schools and, in particular, through residential schools. Education would, Frank Oliver, the Minister of Indian Affairs, declared in 1908, “elevate the Indian from his condition of savagery” and make “him a self-supporting member of the State, and eventually a citizen in good standing.”3

The pictures are, then, both images of what became in this period the primary object of that policy: the Aboriginal child, and an analogy of the relationship between the two cultures – Aboriginal and White – as it had been in the past and as it was to be in the future. There, in the photograph on the left, is the young Thomas posed against a fur robe, in his beaded dress, his hair in long braids, clutching a gun. Displayed for the viewer are the symbols of the past – of Aboriginal costume and culture, of hunting, of the disorder and violence of warfare and of the cross-cultural partnerships of the fur trade and of the military alliances that had dominated life in Canada since the late sixteenth century.

Thomas Moore, as he appeared when admitted to the Regina Indian Industrial School (Saskatchewan Archives Board, R-82239 [1])

Thomas Moore, after tuition at the Regina Indian Industrial School (Saskatchewan Archives Board, R-82239 [2])

Those partnerships, anchored in Aboriginal knowledge and skills, had enabled the newcomers to find their way, to survive, and to prosper. But they were now merely historic; they were not to be any part of the future as Canadians pictured it at the founding of their new nation in 1867. That future was one of settlement, agriculture, manufacturing, lawfulness, and Christianity. In the view of politicians and civil servants in Ottawa whose gaze was fixed upon the horizon of national development, Aboriginal knowledge and skills were neither necessary nor desirable in a land that was to be dominated by European industry and, therefore, by Europeans and their culture.

That future was inscribed in the photograph on the right. Thomas, with his hair carefully barbered, in his plain, humble suit, stands confidently, hand on hip, in a new context. Here he is framed by the horizontal and vertical lines of wall and pedestal – the geometry of social and economic order; of place and class, and of private property the foundation of industriousness, the cardinal virtue of late-Victorian culture. But most telling of all, perhaps, is the potted plant. Elevated above him, it is the symbol of civilized life, of agriculture. Like Thomas, the plant is cultivated nature no longer wild. Like it, Thomas has been, the Department suggests, reduced to civility in the time he has lived within the confines of the Regina Industrial School.

The assumptions that underlay the pictures also informed the designs of social reformers in Canada and abroad, inside the Indian Department and out. Thomas and his classmates were to be assimilated; they were to become functioning members of Canadian society. Marching out from schools, they would be the vanguard of a magnificent metamorphosis: the savages were to be made civilized. For Victorians, it was an empire-wide task of heroic proportions and divine ordination encompassing the Maori, the Aborigine, the Hottentot, and many other indigenous peoples. For Canadians, it was, at the level of rhetoric at least, a national duty – a “sacred trust with which Providence has invested the country in the charge of and care for the aborigines committed to it.”4 In 1880, Alexander Morris, one of the primary government negotiators of the recently concluded western treaties, looked back upon those agreements and then forward, praying: “Let us have Christianity and civilization among the Indian tribes; let us have a wise and paternal Government … doing its utmost to help and elevate the Indian population, … and Canada will be enabled to feel, that in a truly patriotic spirit our country has done its duty by the red men.”5

In Canada’s first century, that “truly patriotic spirit” would be evident in the many individuals who devoted their “human capabilities to the good of the Indians of this country.” In the case of Father Lacombe, Oblate missionary to the Blackfoot, for example, the “poor redman’s redemption physically and morally” was “the dream of my days and nights.”6 According to Canada’s first Prime Minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, the nation, too, dreamed of discharging its benevolent duty. A national goal, he informed Parliament, was “to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the inhabitants of the Dominion, as speedily as they are fit to change.”7 With the assistance of church and state, wandering hunters would take up a settled life, agriculture, useful trades and, of course, the Christian religion.

Assimilation became, during Macdonald’s first term, official policy. It was Canada’s response to its “sacred trust” made even more alluring by the fact that supposedly selfless duty was to have its reward. The Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, L. Vankoughnet, assured Macdonald in 1887 that Indian expenditures “would be a good investment” for, in due course, Aboriginal people, “instead of being supported from the revenue of the country, … would contribute largely to the same.”

Education, as Scott indicated, was the most critical element of this assimilative strategy. Vankoughnet, in his memo of 1887 to the prime minister, was doing no more than reflecting the common wisdom of the day when he wrote:

“That most difficult problem” was to be solved not only through “persistent” tuition but also, more specifically, by residential school education, which, initially, took two forms: “boarding” schools, which were situated on or near a reserve, which were of moderate size and which taught reading, writing and arithmetic, agriculture, and the simple manual skills required by farmers and their wives; and “industrial” schools, such as Thomas’s Regina Industrial School, which were large, centrally located, urban-associated trade schools and which also provided a plain English education. “It would be highly desirable, if it were practicable,” the Department wrote in its Annual Report of 1890 “to obtain entire possession of all Indian children after they attain to the age of seven or eight years, and keep them at schools … until they have had a thorough course of instruction.” The Department was confident that if such a course were adopted “the solution of the problem designated ‘the Indian question’ would probably be effected sooner than it is under the present system” of day schools.

By 1890, the government had been committed for just over a decade to the development of a system of residential schools of “the industrial type.”9 That commitment had sprung from the recommendations of the now-famous Davin Report of 1879. Nicholas Flood Davin, a journalist and a defeated Tory candidate, had been rewarded for his electoral effort by Macdonald with a commission to “report on the working of Industrial Schools … in the United States and on the advisability of establishing similar institutions in the North-West Territories of the Dominion.” Senior American officials who Davin visited, Carl Schurtz, the Secretary of the Interior, and E.A. Hayt, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, evinced the greatest confidence in the efficacy of the industrial school, which was, Davin was informed, “the principal feature of the policy known as that of ‘aggressive civilization,’” their policy of assimilation. Day schools had proven a failure “because the influence of the wigwam was stronger than the influence of the school.” Indeed, support for this thesis came, he claimed, from Cherokee leaders he met in Washington. They described the “happy results of Industrial Schools” and convinced him “that the chief thing to attend to in dealing with the less civilized or wholly barbarous tribes, was to separate the children from the parents.”

Next on Davin’s agenda was a trip to the school at the White Earth Agency in Minnesota. He was obviously impressed. The school was “well attended and the answering of the children creditable…. The dormitory was plainly but comfortably furnished, and the children … were evidently well fed.” The whole reserve had an air of progressive development, traceable, in the opinion of the agent, to the school. Subsequent meetings in Winnipeg with “the leading men, clerical and lay, who could speak with authority on the subject” must have confirmed his American observations, for Davin’s report gave unqualified support to the “application of the principle of industrial boarding schools.” He submitted, as well, a detailed plan for beginning such a school system in the west that he probably worked out with those authorities – Bishop Taché, Father Lacombe, the Honourable James McKay and others.10

While the Davin Report may properly be credited with moving the Macdonald government to inaugurate industrial schools in the 1880s, it is far from being, as it is often characterized,11 the genesis of the residential school system in Canada. Indeed, when Davin submitted his report, there were already in existence in Ontario four residential schools, then called manual labour schools – the Mohawk Institute, and the Wikwemikong, Mount Elgin, and Shingwauk schools; and a number of boarding schools were being planned by missionaries in the west.

Furthermore, the report does not answer the most important questions about the beginning and intended character of the residential school system. Why did the federal government adopt a policy of assimilation? What was the relationship between that policy, its ideology and structures, and education, particularly residential schools? Not only are the answers to such central questions not in the Davin Report, but neither are they found in any single report in the early years after Confederation. Indeed, to discover the roots of the Canadian residential school system, we must make recourse to the history of the pre-Confederation period of Imperial control of Indian affairs. It was in that earlier era that the assimilative policy took shape with the design of programs for the “civilization” of the Indian population of Upper Canada. The policy was then given a final legislative form, in the first decade after Confederation, with the determination of the constitutional position of Indian First Nations expressed in two early Indian acts: 1869 and 1876.

The Imperial policy heritage of the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s, supplemented by federal legislation and programming in the first decade of Confederation, was both the context and the rationale for the development of residential schools, which in turn constituted part of the most extensive and persistent colonial system – one that marginalized Aboriginal communities within its constitutional, legislative, and regulatory structure, stripped them of the power of self-government, and denied them any degree of self-determination. As a consequence, Aboriginal people became, in the course of Canada’s first century, wards of the Department of Indian Affairs and increasingly the objects of social welfare, police, and justice agencies.

The result o...