![]()

THE CITY

THE INDIGENOUS LIFE AND DEATH that this book discusses occurred within a particular city, province, and nation, and this context is the focus of this chapter. The histories of colonialism and dispossession we engage here are pervasive and global. But they are also local and specific. To understand what happened to Brian Sinclair during those thirty-four hours in 2008, we need to begin with the particular place in which it occurred. This approach helps bring to light the intricacies of the colonial project and how it produced the death of Brian Sinclair. In offering a place-based historical account, we illustrate the enduring presence of Indigenous people here. We begin with the city of Winnipeg and the province of Manitoba within the nation state of Canada.

The city where Brian Sinclair lived most of his life and spent his last thirty-four hours is located on the storied and ancient lands of Anishinaabeg, Cree, and Metis people. The Red and Assiniboine Rivers connected Anishinaabeg and Cree communities to Indigenous people throughout the Americas. Archaeological research confirms oral archives that situate the Forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers as a site of human settlement and trade for at least 6,000 years.1 Records indicating Indigenous agriculture at the Forks are confirmed by archaeological evidence of intensive agriculture dating from the early 1400s.2 The inhabitants of these lands were not static societies awaiting European arrival, but societies in motion and transition. Anishinaabeg people came west from Lake of the Woods in the late eighteenth century and were welcomed through traditional protocols by Cree and Assiniboine people.3

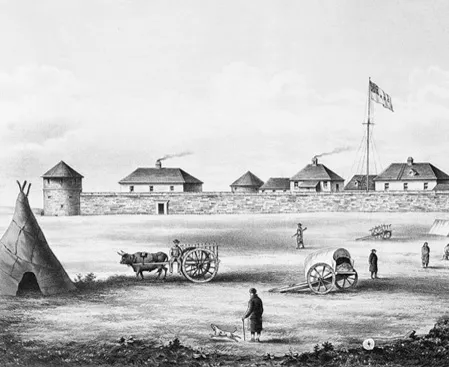

Figure 3. A nostalgic vision of Upper Fort Garry, built in 1822 near the forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. This was painted around 1881, about the time when the fort was demolished.

These territories were part of the expansive space that was, in 1670, claimed, in an odd sort of imperial way, as both British and Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) territory. As historian Michael Witgen argues, “Laying claim to possession of the western interior in this fashion was, for all practical purposes, an action of political fiction.”4 Britain and its colonial settlements were a long distance away, and this expanse of land remained very much an Indigenous space occasionally interrupted by a small post defended by a few garrisoned soldiers. The arrival of a modest number of settlers in 1812 shifted but did not radically alter the fact that this remained an Indigenous place.

From the late eighteenth century onwards, the Forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers were a particular space of Metis community. The Metis are a post-contact Indigenous people anchored in land, culture, and history.5 Particularly critical here was a series of interconnected communities along the lengths of both rivers known by a number of names, but most often as the Red River colony or settlement. By the middle decades of the nineteenth century, Red River was a thriving and overwhelmingly Metis society. Of the roughly 12,000 people enumerated as permanent residents in Red River in 1870, about 10,000 were described as either “half-breed” or “Metis,” and another 560 as “settled Indians” with homes and farms. Of the 1,563 who were enumerated as “white,” nearly half had been born in the Northwest and were likely to have had lineage and kin ties that linked them, in a variety of ways, to Indigenous people.6

Figure 4. Upper Fort Garry in the 1870s. Located in what is now downtown Winnipeg, the fort was the site of the meeting of the Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia under the leadership of Louis Riel in the summer of 1870, and where Wolseley’s troops were later garrisoned.

Historian Damon Salesa has shown how nineteenth-century racial logic was both global and remarkably local.7 On the one hand, racial thinking and practice were consolidated and instrumentalized in the middle years of the nineteenth century. Yet this process played out in particular ways, including in the fur trade and in and around Red River. Intimate relationships and families formed by white men and Indigenous women that had been the bedrock of fur-trade society became less common, especially for the elite. A series of high-profile controversies in Red River worked to cumulatively undermine the moral authority of Indigenous women. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries Indigenous men regularly rose in the colonial and fur-trade ranks if they had sufficient family resources, connections, and skills.8 This changed, in large part if not entirely, in the years following the reorganization of the western fur trade in 1821. By the 1830s, it was rare for Indigenous men to be promoted beyond the rank of postmaster.9

Yet Red River’s powerful Indigenous elite survived these challenges of the 1820s and 1830s. Alexander Kennedy Isbister (1803–1890) was born to a Cree-Metis mother and an Orcadian father. Isbister excelled at school in Red River, but when he joined the HBC service he was predictably, and insultingly, appointed to the position of postmaster. Isbister left Red River for the United Kingdom, where he trained as a barrister and moved in influential, upwardly mobile circles. In correspondence he endeavoured to explain the particular, layered colonial society of his homeland, and its Indigenous elite, to a confused British public. In 1859, Isbister explained that, “with the exception of the small Scotch community at Red River and a few missionaries’ wives, every married woman and mother of a family above the grade of an Indian throughout the whole extent of the Hudson’s Bay Territories, is of mixed race, and is with her children the inheritor of all the wealth of the country—the fortunes made in the fur-trade, and the valuable property accumulated in the Red River Colony—must of itself invest this class with a high degree of interest and importance.” The sons of HBC officers, he went on, had inherited “often considerable property,” were “generally well educated (many of them in universities in Great Britain, Canada and the United States),” and occupied the usual positions of the local elite, including “the Sheriff of the Red River Colony, the medical officers, the surveyors, the postmaster, the entire staff of the teachers in schools and a fair proportion of the Clergy of the Christian Missionaries and other societies,” as well as the “Municipal Council of the Red River Settlement.”10

The last third of the nineteenth century was a complicated and consequential time for this part of the world. A series of linked colonial manoeuvres variously occurred in London and Ottawa via some important legislation: first, the British North America Act (1867), which created Canada as a particular sort of nation within the British Empire, one with distinct imperial ambitions of its own with respect to the territories lying to its north and west; second, Britain’s Rupertsland Act in 1868; and third, Canada’s 1869 “Act for the Temporary Government of Rupert’s Land.” As Adam Gaudry explains, these three pieces of legislation were thought to “unilaterally transfer the possession of a vast peopled landscape from one authority of empire, the Hudson’s Bay Company, to another—Canada.”11 Under the leadership of Louis Riel, Red River would object, strenuously, militarily, and successfully, to these acts of colonial fiat and establish their own government. The winter of 1869–70 was a tumultuous one, including the execution of Canadian Thomas Scott by the provisional government for refusing to acknowledge its authority.

As a direct result of this resistance, Manitoba entered Confederation not as a colony of Canada, but as a small province within it, set by the terms of the Manitoba Act of 1870. Manitoba was the only Canadian province to enter Confederation on its own, explicitly Metis, terms, and in armed conflict. The early months of Manitoba’s existence as a province suggested that this history and these aspirations would persist: in the summer of 1870, electors, including “settled Indians” from St. Peter’s, and maybe even some women, elected the Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia. Twenty-one of its twenty-eight members were Metis, half French- or Michif-speaking and half English-speaking; most also spoke Cree or Anishnaabemowin.12 What would unfold over the next few decades, however, would create a city and a province that looked very different from what people at Red River may have imagined in the 1860s, and fought for during the long winter of 1869–70.

The transformation of Red River from this layered, variegated Indigenous place into a Canadian and settler space was accomplished in a number of ways, including sustained violence. Historians of Red River refer to a “reign of terror” between 1870 and 1872. The Red River Expeditionary Force, made up of more than 1,000 Canadian militiamen, arrived in 1870 and was garrisoned at Upper Fort Garry, in what became a nest of buildings representing the new colonial order, and which included the Dominion ...