- 290 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Creativity, Innovation and the Cultural Economy

About this book

This collection brings together international experts from different continents to examine creativity and innovation in the cultural economy. In doing so, the collection provides a unique contemporary resource for researchers and advanced students. As a whole, the collection addresses creativity and innovation in a broad organizational field of knowledge relationships and transactions. In considering key issues and debates from across this developing arena of the global knowledge economy, the collection pursues an interdisciplinary approach that encompasses Management, Geography, Economics, Sociology and Cultural Studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Creativity, Innovation and the Cultural Economy by Andy C. Pratt,Paul Jeffcutt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Introduction

1

Creativity, innovation and the cultural economy

Snake oil for the twenty-first century?

Andy C. Pratt and Paul Jeffcutt

Introduction: surveying the territory

Creativity has recently joined innovation and become a key term in debates about the knowledge economy. It is difficult to find a popular book on this topic at present without ‘cultural’ or ‘creative’ in the title. In one sense, this attention is obvious: which person, group, firm, city or region would aspire to be uncreative (and not innovative)? Put in this way, of course, nobody. But is this the right question to ask? Such characterisations of innovation and creativity present them as ‘magic bullets’: one shot solutions to problems. It is tempting to ask whether innovation and creativity might not be the new ‘snake oils’. Certainly, no one has managed to bottle either. This is not to suggest that creativity and innovation are unimportant, rather that we have to be careful how we understand and work with them. In this chapter we argue that this recent enthusiasm for creativity needs to be placed in context and, in particular, connected to strategic responses to competitive and globalised challenges in the contemporary economy.

There are two main types of strategic response from those concerned with managing the economy. In the first response, it is believed that competitiveness can be maintained by downward pressure on costs that are either met by the substitution of labour by technology, or by cheaper labour (usually in a different region or nation state). In the second response, competitiveness can be maintained through innovation in products and services. The focus on ‘price’, which underpins the first response, has been termed ‘old competition’, whilst the focus on quality, innovation (and creativity) has been called ‘new competition’ (Best, 1990).

In ‘new competition’, innovation relies upon creativity in the generation of novel products and services. Indeed, in enterprises, it is creativity (or invention) that stimulates and supports the achievement of innovative outputs. Organisations may thus become configured to value creativity and innovation as sources of competitive advantage rather than as additional costs. Hence, the second cycle places emphasis upon loose networks of enterprises that can mix and match skills and expertise to produce short runs of new products and services of high quality at short notice.

With creativity and innovation at a premium in short product runs and rapidly changing product ranges, the key question that follows is how to maximise creativity and innovation in any individual, enterprise, region or economy. In order to respond effectively, one has to understand where creativity and innovation is ‘located’. Obviously, individuals are a primary source of creativity (and invention), but it is somewhat short-sighted to simply seek to increase the ‘creativity’ quotient of each individual in the hope that this will make a significant difference. Whilst we acknowledge that all humans have the potential to be engaged in ‘creative’ activities we would reject a ‘psychological pathology’ of creativity which reduces it to some ‘hard-wired’ aspect of the brain. Likewise, we find the binary categorisation of activities – ‘creative’ or ‘not’ – unhelpful. Our emphasis here is on the mobilisation of creativity – in other words, how the ‘creativity effect’ is achieved. This effect, we argue, will always be socially and economically situated.

Are innovation and creativity one-and-the-same? Certainly, it is common usage that creativity is the ‘ideas’ part of innovation; innovation usually being characterised as the practice of implementing an idea (for example, see Amabile et al., 1996). Others dispense with creativity altogether replacing it with stages of innovation (for example, see Van de Ven et al., 1999). For others still, creativity is quite different from innovation. Creativity encompasses new knowledge, whereas innovation may not be creative and can be incremental (for example, see Bessant, 1998). On the other hand a common measure of innovation is the number of patents registered. As has been extensively discussed, such measures mis-identify innovation processes: a patent is only valorised when it is turned into a product. Despite their differences most points of view acknowledge that context is important for innovation and creativity.

New ideas certainly require a context in which they may be nurtured, developed and passed on, or made into something more generally useful. Some contexts and settings appear to enable creativity and innovation to flourish – but is creativity and innovation all context? Clearly, creativity and innovation do require both context and organisation – indeed, creativity and innovation do appear to be embedded in a complex interaction of the two. In other words, creativity and innovation need to be addressed as a process (requiring knowledge, networks and technologies) that enables the generation and translation of novel ideas into innovative goods and services. This key (but still poorly understood) process in the contemporary knowledge economy has been underlined by recent interest in creative industries and the cultural economy.

In Scott’s (2007) view, the rising importance of the cultural economy signifies a phase of convergence and culturalisation of global capitalism. However, the debate about the cultural economy, whilst certainly important, may be distracting when mired in this binary discussion. What, if anything, is specific, or exceptional, about the cultural industries that comprise the cultural economy (as opposed the culturalised economy)? What is the relationship between the cultural economy and the knowledge economy? Is the cultural economy, as some authors claim, the leading edge of economic change that other industries will follow?

A better understanding of this cultural economy is thus crucial to understanding the global complexity of the contemporary knowledge economy. However, currently there is a lack of strategic knowledge about the relationships and networks that enable and sustain creativity and innovation in the cultural economy. Recent work on these problems, such as those identified in the papers collected in this volume, emphasises the significance of particular types of knowledge relationships in particular situations.

The aim of this book is to examine the formulation, relationships between and practices of creativity and innovation in the cultural economy. The collection comprises of six pairs of chapters that examine the issue from the perspective of different industries within the cultural economy. We have chosen to offer pairs of chapters in order to stress the importance of an openness to methodological variety in the analyses; this objective also results from our starting point, namely that both quantitative and qualitative methods are required, as well as a range of approaches, within and across both. The social sciences have been in the grip of a ‘cultural turn’ in recent years; namely, they have sought to develop a less functional or reductive approach to economy and society (Amin and Thrift, 2004). At present, we are far from a consensus as to what such a new ‘approach’ might be. However, there has been a lively exchange about the cultural and more broadly, social, aspects of economic life. The irony is that until now the cultural turn has not been matched by a similar focus on the cultural economy as an object of analysis. Consequentially, our approach has been to seek out the social and cultural dimensions of economic life of the cultural economy. Lest we back into another difficulty, we would immediately state that we reject any hard and fast distinction between the socio-cultural and the economic; we are working on the basis that they are co-constitutive (Pratt, 2004).

A second starting point is that the cultural economy is characterised by variety; obviously, collectively it may be argued that the cultural economy is distinguishable from the ‘rest’ of the economy in some important ways, but there are also significant variations across particular industries. In effect, this blurs the distinction between the cultural economy and the ‘rest’ by acknowledging commonalities as well as differences. There has been a sustained debate over the last decade about the naming and definition of the cultural economy. Labels such as creative industries, cultural industries, creative economy and cultural economy, or cultural and creative industries have all been used. Whilst academic cases can be made for a differentiation between them, the overwhelming policy discourse is one in which they are used interchangeably (see Pratt, 2005). This does not help clarify the concept, nor make it operational. Thus, the real struggle is to develop meaningful statistical definitions from the definition popularised by the UK Department of Culture, Media and Sport, which identifies 13 industries that comprise the ‘creative industries’ (see Box 1.1). This is significant because it has been copied extensively by many policy makers and academics. Despite the global popularity of this definition, it does have a number of significant shortcomings (see Jeffcutt, 2008): for example, it focuses on outputs but excludes the public sector, informal activities, and the ‘production of culture’. A definition developed for UNESCO – the framework for cultural statistics (Box 1.2) – is far more useful in an analytic sense as it is based upon a ‘production chain’ model that exposes the dynamics that underlie the outputs; it is the one that we prefer to use here.

Box 1.1 The UK Department of Culture Media and Sport definition of the ‘creative industries’ (DCMS, 1998)

Advertising

Architecture

Arts and Antiques

Crafts Design

Designer Fashion

Film

Leisure Software

Music

Performing Arts

Publishing

Software

Television and Radio

Third, we point out that the cultural economy and the ‘rest’ of the economy is not static, nor universal. The cultural economy has emerged from being a relatively insignificant part of economic life to a major player in advanced economies. Moreover, some have argued that the rise of the cultural economy is part-and-parcel of a wider transformation of the whole economy: the culturalisation of the economy. From a cultural point of view many argue that the commodification of culture has led to its economisation, placing bias in favour of quantity and against quality of cultural products and artefacts. Thus, it is increasingly difficult to disentangle the rise of the cultural economy from the transformation of the ‘rest’, and it is unclear what the causal direction and strength is. For many policy makers it is this innovation or creativity ‘spill-over’, and not the intrinsic or substantive economic and cultural value, that is the prize to be gained from the promotion of the cultural economy. Such a view rests on the assumption that culture and entertainment are necessarily inferior and dependent upon the ‘real economy’.

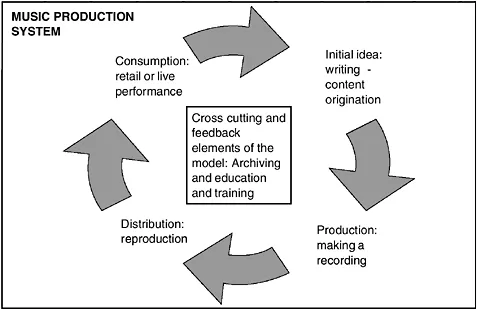

Box 1.2 The cultural industries production system, the example of music (see UNCTAD, 2008)

Aside from the growth of the cultural economy, there has been discussion as to whether it might be different in organisational terms. Certainly, there appear to be some common characteristics of the cultural industries (See box 1.3), evidenced by many studies. The further dimension of this question is that the cultural economy does seem to operate variously in different industries, and it does not operate equally the world, or nation over. One of the distinctive points about the cultural economy is its unequal distribution, and asymmetric power/value-structure of the key organisations and networks, as well as its tendency to co-locate or cluster in a small number of places. Obviously, this has consequences for both economic and cultural development. Recent debates about cultural production chains have raised the issue as to whether the upgrading of activities in some locations to higher value activities is possible (for example, from production to design) (Pratt, 2008b). Critically, this organisational variation concerns the changing scale of operation of the cultural economy, and the variety of regulatory and governance contexts within which it operates. In a similar manner to which ‘varieties of capitalism’ have been identified (Hall and Soskice, 2001), we would expect to find ‘varieties of cultural economy’ and variations within the cultural economy.

Box 1.3 Characteristics of the cultural industries

- An industrial structure better characterised as an ecosystem

- Overlapping networks, mediated by intermediaries and facilitated by the movement of freelance workers and informal interaction

- A relative lack of middle-sized companies

- A preponderance of short life, project based companies with freelance workers

- Massive market uncertainty, coupled with very high risk of failure

- Very rapid turnover of innovation, fashion and the product cycle

- A ‘winner takes all’ system: massive differences between what it means to win and lose

- Tension between content regulation and competition regulation

Fourth, we want to highlight questions about the very notions of creativity and innovation, their relationship, and their character. We seek to challenge what we regard as a simplistic and superficial notion that creativity and innovation are separate and distinct ‘things’ that can act as inputs, or outputs, or are connected in a unilinear process. Our stress is upon the exploration of the relational nature of these ideas. As we will note, thinking about creativity and innovation in a relative manner opens up a fruitful line of investigation.

However, before we get to this point in our discussion it is necessary to distinguish our position in relation to some common, or taken for granted, assumptions. The ‘big questions’ that are often brought to the table in debates in this field are: What is the relationship between creativity and innovation?; Is innovation or creativity in the cultural economy the same, or different, to that found in the ‘rest’?; and, What is the relationship between the cultural economy and the ‘rest’ of the economy (does it, in effect, act as a creative stimulus)? The main body of this chapter sketches out our position on, and relationship to, these questions. Our approach mobilises a multi-disciplinary background, drawing upon sociology, economics, geography and management studies.

Building a better mousetrap

What counts as innovation, and how might it be understood? The answer is either to ‘build a better mousetrap’, or to originate ‘the very idea of a mousetrap’. That is, make something everyone will want, and no-one has thought of before. With mousetraps as with innovation more generally it is difficult to separate out the incremental from the revolutionary change. Thus, it is common to fall back on a proxy, something that is believed to be associated with innovation. Here, the common culprit is ‘technology’. Of course, technology is another term for the application of a novel process or product innovation. However, as we will note below ‘throwing technology at a problem’ does not make an innovation, it merely offers a way in which a product or process can be modified. Whilst it is clear that there is significant investment in new technology, it is not so clear that this has directly led to comparable, or greater, increase in output. Many researchers argue that claims about the role of new technologies in economic growth have generally been based upon ‘hope value’ rather than fact (Jorgensen and Stiroh, 2000; Oliner and Sichel, 2000). Furthermore, it is not obvious whether new technologies cause things to be done differently, or are simply the exploitation of opportunistic changes. There are clear cases where the possibilities of new technology are deployed by managers to achieve reorganisation and cost savings, but such changes are not a necessary outcome of the application of technology. Classic examples of organisational change are the adoption of digital newspaper production in London in the 1980s, self-operated news reporting adopted by television companies, and the adoption of ‘bimedia’ strategies by both broadcasters and newspapers in the early 2000s. Interestingly, changes in film production appear less significant, with much of the attention being placed on the use of special effects for artistic expression; digitisation has not yet greatly impacted upon distribution and exhibition.

Generally, we can view innovation and creativity in at least two ways with particular ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Part 1 Introduction

- Part 2 Advertising

- Part 3 Music

- Part 4 Film and TV

- Part 5 New Media

- Part 6 Design

- Part 7 Museums/Visual Arts/Performance

- Part 8 Conclusion

- Index