![]()

1 Introduction

Moving on from Images of Red Guards, the Tank Man and Little Emperors

Discourses on a Changing China and its Youth

Television and radio station schedules, together with the pages of newspapers, have become increasingly bloated with China-related stories. Sexual promiscuity in Shanghai, the grievances of migrant workers in Guangdong, the heavy burdens of secondary school children in Anhui, the Olympic Games in Beijing, unrest in Tibet and Xinjiang, Chinese involvement in Africa and on the global stage, contaminated milk and, in tragic circumstances, the earthquake in Sichuan are but just a few of the multifarious ways in which China has appeared recently in mediated forms, feeding what seem to be insatiable appetites for the country and its people. In contrast to the past, when stories of China were typically set either against backdrops of rice paddies, misty landscapes and lakes littered with lotus flowers or, perhaps more recently, Tiananmen Square in Beijing, accounts now unfold within an altogether different set of locations, such as the Bird’s Nest Olympic Stadium; the soaring architectural hyper-modernity of the new business district in Shanghai’s Pudong; the Three Gorges Dam spanning the Yangtze River; Shanghai’s elevated neon-lit expressways; and karaoke establishments, multinational corporations, 24-hour massage parlours, department stores, Irish bars, Starbucks coffee shops, discos and clubs, Carrefour hypermarkets, gated communities and luxury hotels.

Such renditions of China exist within a discourse of transformation that relentlessly applies a vocabulary of change and transition to almost every aspect of China. Even the political system, for so long perceived to have remained largely frozen (Perry and Selden 2000: 6), has become subject to such a discourse, with commentators acknowledging that in the past two decades or so the socialist regime of China has undertaken major re-orientations in its approach to social and economic development and to governance. Seen to be at the forefront of depictions of a changing China are the country’s youth, to such an extent that they are often seen to epitomize the transformations occurring around them. As Elizabeth Croll has observed:

Perhaps there has been no more potent image of change in China’s postrevolutionary years than the image of current generations of youth as they participate in new forms of recreation and entertainment, consume in the new world of goods and enter the global ranks of the ‘young, hip and cosmopolitan’.

(2006: 204)

Red Guards waving copies of Mao’s Red Book have been almost entirely cut from the script and even the ‘anonymous heroic figure … [who in 1989] broke from the crowds … in contest with the powerful but equally anonymous forces of the State’ (Dutton 1998: 17) has been reduced to playing only a minor role. Such characters have been replaced by an ensemble cast who are for the most part constructed as individuals who, having sidestepped Maoism and Confucianism, have instead become attached to heady consumption (see, for example, Cadwalladr 2007) and computer games: China’s Little Emperors.

As Chinese youth have performed a dramatic function in Western stories about China, so have they served as a vital means through which China has told stories about itself. In contrast to the West, where youth is associated with inexperience, impulsiveness and rebelliousness, the Chinese term of youth (qingnian, 青年 translated literally as ‘young or green years’) has traditionally been associated more favourably with hope, courage and dynamism (Kwong 1994: 248). Chinese youths have been central protagonists in most, if not all, political movements of the twentieth century, for example by helping to ‘overthrow the dynasty’ (Richard and Wilson 1970: 97) in 1911 and by being central to the May Fourth Movement in 1919 (Chow 1960). In the process they have become a powerful symbol of regeneration and national salvation (Tang 1996: 13), representing reason, modernity and science (Dikötter 1995: 147).

As in Western discourses, Chinese youth has shifted in the minds of the wider Chinese public from being ‘vanguards of the population … and “forecasters” of China’s future orientation’ (Song 2003: 6) to being associated with a whole array of rather less positive qualities and behaviours. In the 1980s, Chinese officials and media began to talk of the existence of a youth problem (Hooper 1985) whilst Chinese educators began to use the phrase ‘ideological crisis’ to describe youth culture (Kwong 1994: 247). Youths have subsequently been depicted as contemplative, wounded, wasted, lost; fallen (Liu 1984: 976); complex; practical; without thought for the future, mankind or the motherland; distant to the Party; doubting of socialism; boastful; dishonest; arrogant; and ‘practical, utilitarian, and individualistic, a kind of self-centred “me-generation”’ (Luo 2002: ix). By the 1990s, university students were no longer regarded as ‘favourites of society’ (shehui de chonger, 社会的宠儿) (Luo 2004: 781), and were instead ridiculed as a generation grown up in their parents’ arms (baoda de yidai, 抱大的一代), a broken generation (kuadiao de yidai, 垮掉的一代), and a generation of no theme (wu zhuti de yidai, 无主题的一代); cultural orphans in a vacuum of values, ‘so disappointed with the future of the country and their own future … the lowest-spirited and most cynical generation in the last 100 years’; pragmatic and individualistic (Luo 2004: 781).

Studies published in the late 1990s and early 2000s, especially those based on research conducted on university campuses, have discerned value changes (Wang 2006: 234) highlighting awakened individualism (Moore 2005) and self-awareness (Wang 2006: 234), a stronger sense of independence (Wang 2006: 234) which prioritizes self-interest over other people’s interests, a fast-growing pessimism and consumerism contrasting sharply with the socialist values of their parents and the Confucian values of their grandparents (Whyte 2003a: 14). In her book Only Hope: Coming of Age under China’s One-Child Policy, Vanessa Fong discusses the proliferation of terms coined to describe single children in China, who are perceived to be the beneficiaries of the 4–2–1 factor in urban China, where four grandparents and two parents coddle one child (Jun Jing 2000: 19): precious lumps (baobei geda, 宝贝疙瘩), pampered (jiaoguan, 娇惯), spoiled (chonghuai le, 宠 坏了), ‘ “little suns” (xiao taiyang, 小太阳) because their parents’ lives revolved around them’ (Fong 2004a: 29), whilst Jun Jing refers to the image of Little Emperors (xiao huangdi, 小皇帝) made popular in both Chinese and Western media who are ‘showered with attention, toys, and treats by anxiously overindulgent adults’ (2000: 1). More recently added to the derogatory terms utilized to refer to young Chinese are phrases such as fu er dai (富二代, rich second generation) and ken lao zu (啃老族, which refers to the idea that young Chinese eat away at their older relatives’ savings) whilst the term zai tangshui li pao da de (在糖水 里泡大的) is used to refer to the sweet and materially comfortable environment in which contemporary youths are perceived to have come of age.

It is in the context of such views that this book about young people growing up in urban China has been written. Although China and its youth appear so often within a whole set of popular media forms, it is the contention of this book that the views presented therein are frequently misleading and that a series of stereotypical, two-dimensional, simplified shots of China and its youth have emerged which have become fixated upon and made iconic by media intertextuality and that now dominate the entire representational space. In this book, I argue that there is a tension between descriptions of the effects of change and the more complicated, ambivalent ways informants talk about their experiences of, and feelings about, having grown up amidst such profound transformations. Like de Kloet, I hope to show that generalizations about such things as the egocentric, blindly patriotic and apolitical attitudes of young Chinese are too sweeping (2010: 24). In this introductory chapter 1 first identify some major themes in representations of China and its youthful population, whilst also seeking to explain why such views have gained so much traction in Western imaginations. I then discuss Chinese depictions of its own youth, and suggest that these visions say rather more about the authors of these discourses than they do about Chinese youth itself. Finally, I explain the basis upon which this book has been written, highlighting my own theoretical orientation, the research methods I have used and the scope and organization of this book.

Sorting through Western Snapshots of China and Its Youth

A number of media representations of China are spectacular by virtue of the fact that they gaze into places that most ordinary people, whether Western or Chinese, are denied access. The deceptively simply titled China that aired on BBC2 (2006) is a case in point. Built up over the course of four hours, the viewer is swept away in an exhilarating story that includes such features as temples in Tibet, a labour camp for females outside Beijing, a rural wedding and a village election. In Phil Agland’s no less stunning documentary Love and Death in Shanghai (2007), the director’s cut of Shanghai Vice (1999), stories unfold about the murder of a school teacher; the interrogation, trial and execution of her murderer; a 60-year-old landlady looking for Mr Right and her young female lodger; a little boy with a heart condition; a soon-to-retire opera teacher tutoring his final student; and a pair of middle-aged friends trying to liven up their sex lives (whilst complaining a lot along the way about their husbands).

Generally speaking, however, being in the media spotlight means being subject to processes of simplification. As Mullen, writing in relation to American representations of Tibet, observes, the crafting of stories often relies upon quick quotations and rapid montages of images (1998). Consider, for example, the tendency for China to be depicted using a quickly edited, often speeded up, set of images such as cranes, under-lit elevated roadways, construction sites and the like. Sometimes as a way of enhancing the visually arresting nature of the relentless headspinning transformation that is encoded by these images, the montage often cuts to images of a rather different kind: rural hinterlands, for example, coloured in timeless browns and yellows. Accompanying such images is typically a set of ‘talking head’ experts and a voice-over which, with gravitas, reels off what equates to a must-know set of China facts such as: ‘one-party state’, ‘China’s century’, ‘set to pass the US’, ‘one-child policy’, ‘human rights violations’ and so on.

Upon closer examination, even the aforementioned China (BBC2 2006) and Shanghai Vice (1999) simplify and construct overly polished narratives through their usage of technical, social and ideological codes (Fiske 1989) which ultimately damage the stories within. After re-watching China (BBC2 2006) several times, sometimes with my students, I am struck by how a rigid language of binary oppositions is used as a device to structure the narrative. In the first five minutes, for example, the audience is introduced to a polarized verbal or visual language of big and small, powerful and powerless, rich and poor, city and urban, winter and summer, hot and cold, all of which are presented under the premise that although this might be China’s century, there are internal pressures mounting within the country itself as those who are disenfranchised call for justice. Although as Viner notes, Agland’s Shanghai Vice (1999) ‘represents a monumental achievement’ (1999), the most enlightening part of the films is the focus on ordinary folk and this is, I feel, dulled somewhat by the fact that these stories are set within a broader narrative of transformation that reduces the ambivalence, poignancy and fragmentary nature of those lives depicted, making them act as synecdoche for the whole. Further distracting from these stories of ordinary people is the fact that their lives are set against far-from-ordinary tales of heroin traffickers, anti-riot squads and a murder.

As with representations of China, there is no single image of Chinese youth but a set of caricatures that apply in a number of different contexts. In the family, for example, young Chinese are typically portrayed as despotic, tyrannical ‘Little Emperors’. At school, meanwhile, they are seen as passive, docile automatons incapable of thinking critically who, under extreme pressure, mechanically regurgitate information for the purposes of passing examinations. In cities, they are seen as savvy, consumerist shoppers, whilst through the prism of international disputes in which China has become involved, such as the progress of the Olympic torch across the globe in the early part of 2008, they are seen as spikyhaired, often angry, flag-waving nationalists, depictions which only seem to be magnified once online behaviours are examined.

Such contradictory images – of an angry, yet passive, Little Emperor – are spun together in such a way that, as Bradford Brown and Larson note with regard to how the understanding of adolescence at the outset of the twenty-first century tends to emerge from the observation of related but distinctive features of the lives of youths in different parts of the world, the pictures coalesce to form the impression of a single, moving image (2002: 1). Images of certain youths have been focused upon and these images have been made iconic by media intertextuality. In the early years of the 2000s, for example, the media became fixated upon such youthful figures as Wei Hui, MianMian and, more recently, HanHan largely because they acted, and continue to act, as convenient symbols of the broader narrative that the West had constructed, namely that of China’s openingup and transformation. Such characters, by no means either typical or ordinary, almost equate to synecdoche, such is the way that they are used to stand for some 300 million other Chinese youths.

Such aforementioned Western images emerge from a preoccupation with certain themes. China’s modernization has ushered in a new and as yet not fully conceptualized global landscape in which pre-existing ways of seeing are no longer sustainable. This, to some extent at least, explains why the view of China as static and stubbornly resistant to the tides of change has been displaced by images of the country as hyper-mobile, even out of control. It also explains the sense of bewildered febrile fascination, sometimes accompanied by fear, which often typifies Western commentary on China. Nonetheless, although it is unquestionable that China’s modernization has made the differences between East and West – between ‘developing’ and ‘developed’ – now appear much more fluid, thereby making it difficult for the West to define itself by its contrast with China, it seems there is still an attempt, tacit or otherwise, to read China using a conceptual framework taken from the past (Wasserstrom 2000: 13).

Contemporary views of China are often couched in Orientalist discourses which, put simply, can be defined as Western distortions, purposeful or not, of Eastern traditions and culture, and these misrepresentations can ultimately be patronizing or damaging to the studied cultures. Edward Said argued that when the East is represented in Western discourses it is simultaneously romanticized and demonized, appearing as exotic, backwards, sensuous, despotic and cruel, qualities opposite to Europe’s own self-image (1978).1 By portraying the Orient as ‘Other’ – a different and competing alter ego – Said argued that the West is effectively shoring up its own cultural identity.

Whilst being curious about China’s spectacular modernization, the Western press has remained strangely obsessed with revealing the country’s apparently inherent barbarity. Amidst the ostentation and ceremony of the Olympics in Beijing, for example, they appeared to be half-expecting (even hoping) to witness evidence of human rights violations, student demonstrations and other dramatic instances of underlying social unrest, occurrences that would justify their tendency to demonize. Even the tragic earthquake in Sichuan aroused the scepticism of the American media in particular, which expended a lot of energy searching for evidence of government corruption, poorly constructed buildings, and expressions of rage against the state from people who had, in many cases, lost their entire families.

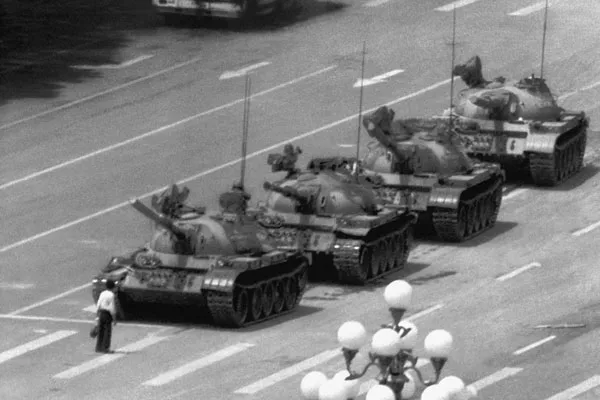

The heart of the problem is that these images only scratch the surface and, like the scratches of an earlier time described by Isaacs (1958), exert a disproportionately large influence over the minds they encounter. Writing in the 1950s, Harold Isaacs identified the interplay of two visions of Chinese in the American imagination: one idea is based on a cluster of admirable qualities such as high intelligence, persistent industry, filial piety, peaceableness, stoicism and coura-geousness; and the other is comprised of negative traits such as barbarism, inhumanity, ruthlessness and faceless might (1958; Wasserstrom 2000: 16). This explains, in part, why the Tank Man (Figure 1.1) has gained so much traction within Western imaginations.

Figure 1.1 The Tank Man (source: AP/Press Association Images).

The Western media portrayal of the events of 1989, as Michael Dutton has so evocatively observed, ‘through the lens of the man versus the tank’ (1998: 17) is attractive for Western observers – myself included – because both of the polarized images of China discussed by Isaacs (1958) are encapsulated in a single picture, the tanks becoming synonymous with a repressive, monolithic state structure, whilst the lone youth becomes a universal symbol for the oppressed. By focusing solely on images such as the Tank Man that are made iconic through media intertextuality, however, much of what is happening either peripherally or entirely outside the camera’s frame is overlooked.

The interaction between the man, carrying a plastic shopping bag as if on his way back from the shop, and the tank was more complex than this crude interpretation suggests, an understanding of which can only begin to emerge when it is seen in context. The tank did not roll over the man, nor did the man overpower the tank. Rather, they faced and sidestepped; they pushed forward and drew back; they prodded and they glared. In essence, they negotiated. The incident itself, furthermore, was not isolated but was, as Luo Xu points out, the consequence ‘of a decade-long transformation of ideology among a vast number of ordinary people at grassroots level’ (1995: 542). Furthermore, the events of 1989 were not isolated, having been preceded in 1986 by widespread clashes between students and school authorities (Kwong 1988: 979). Although the Western press at the time focused on the students’ pleas for democracy, Hong Kong media reported student dissatisfaction with practical issues: students in Beijing, for example, complained about lights being turned off at 11 o’clock in the evening, while students in Nanjing protested about the inclusion of political studies in the curriculum (Kwong 1988: 979). Moreover, the students’ negotiations were prolonged and the issues raised were not simply resolved by the imposition of tanks and machinery. The activity between students and the st...