![]()

1 Challenging the Terrorist Stereotype

Am I crazy or is attacking torture by lobbying the producers of 24 almost as ridiculous as trying to make nuclear power plants safer by urging the producers of The Simpsons to stop letting Homer play with plutonium in the lunchroom of the Springfield nuke plant?

—Peter Carlson, Washington Post

Intentionally or not—and for better and for worse—fiction can play a real role in the construction of political reality. Amid the global war on terror, those in Hollywood and those in Washington would do well to take heed of this fact about fiction.

—Kelly M. Greenhill, Los Angeles Times

In 2004 the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) accused the TV drama 24 of perpetuating stereotypes of Arabs and Muslims.1 CAIR objected to the persistent portrayal of Arabs and Muslims in the context of terrorism, stating that “repeated association of acts of terrorism with Islam will only serve to increase anti-Muslim prejudice.”2 CAIR’s critics have retorted that programs like 24 are cutting edge, reflecting one of the most pressing social and political issues of the moment, the War on Terror. Some critics further contend that CAIR is trying to deflect the reality of Muslim terrorism by confining television writers to politically correct themes.3

The writers and producers of 24 have responded to CAIR’s concerns in a number of ways. For one, the show often includes sympathetic portrayals of Arabs and Muslims, in which they are the “good guys” or in some way on the side of the United States. Representatives of 24 state that the show has “made a concerted effort to show ethnic, religious and political groups as multi-dimensional, and political issues are debated from multiple viewpoints.”4 The villains on the eight seasons of 24 are Russian, German, Latino, Arab/Muslim, Euro-American, and African, even the fictional president of the United States. Rotating the identity of the “bad guy” is one of the many strategies used by TV dramas to avoid reproducing the Arab/Muslim terrorist stereotype (or any other stereotypes, for that matter).5 24’s responsiveness to such criticism even extended to creating a public service announcement (PSA) that was broadcast in February 2005, during one of the program’s commercial breaks. The PSA featured the lead actor, Kiefer Sutherland, staring deadpan into the camera, reminding viewers that “the American Muslim community stands firmly beside their fellow Americans in denouncing and resisting all forms of terrorism” and urging us to “please bear that in mind” while watching the program.6

CAIR is not the only organization that has lobbied 24 to change its representations. Whereas CAIR objected to stereotyping Arabs and Muslims as terrorists, the Parents Television Council, Human Rights First, and faculty from West Point Military Academy objected to 24’s portrayal of torture as an effective method of interrogation. The Parents Television Council was concerned that children would become desensitized to torture; Human Rights First was concerned that viewers might come to perceive certain human beings as deserving of torture, not worthy of human rights; and the West Point faculty were concerned that some of their cadets believed torture was an effective method of interrogation because of 24’s portrayal of it. Tony Lagouranis, former army interrogator, stated, “Among the things that I saw people doing [in Iraq] that they got from television was water-boarding, mock execution, using mock torture.”7

Howard Gordon, one of the writers, responded by stating, “I think people can differentiate between a television show and reality.”8 The writers and producers of 24 explained that the show was fictional, that it was not intended as a documentary or military manual. They went on to say that the torture scenes are for dramatic, entertainment purposes only. Furthermore, the writers and producers of 24 stated that although the character Bauer uses torture and is a U.S. hero, torture is not glamorized because Bauer is traumatized by his use of torture. However, Joel Surnow, executive producer, defended the use of torture in the show, claiming, “We’ve had all of these torture experts come by recently, and they say, ‘You don’t realize how many people are affected by this. Be careful.’ They say torture doesn’t work. But I don’t believe that. I don’t think it’s honest to say that if someone you love was being held, and you had five minutes to save them, you wouldn’t do it.” In contrast, Sutherland expressed concern about the “unintended consequences of the show.” Fox Television network executive David Nevins admits that the show conveys a clear message on the War on Terror: “There’s definitely a political attitude of the show, which is that extreme measures are sometimes necessary for the greater good.… The show doesn’t have much patience for the niceties of civil liberties or due process.”9

In November 2006 members of Human Rights First and West Point met with the writers and producers of 24 to address the potential impact of their representations of torture.10 David Danzig, manager at Human Rights First, explained that the meeting was difficult for 24’s writers and producers because “they have a hugely popular show, and we were suggesting to them that they do something actually a little bit risky, which is change their format. And there’s obviously a lot of money at stake.” Though the 24 crew insisted their depiction of torture should not have an influence on its viewers, it is interesting to note that the story line of the next season (which debuted on January 13, 2008, fourteen months after the meeting) involved Jack Bauer being tried by the U.S. government for his illegal use of torture.

This chapter explores this slippery realm between representations and their potential impacts. Through each facet of this discussion, what arises is a fact that is utterly taken for granted: television mediates the War on Terror. Between 2001 and 2009 the fictional creations of a tiny number of artists and executives shaped the ways that viewer-citizens engaged with the very real war going on around us. As indicated in the opening epigraph, the journalist Peter Carlson thinks that it is ridiculous that a TV drama, rather than the U.S. government, was criticized for its role in torture (and for its representation at that). Whether ridiculous or not, the journalist Kelly Greenhill asserts that it is important to take seriously the power of TV dramas to shape public perceptions of the War on Terror. Throughout the Bush years, TV shows became a crucial way that Americans saw, thought about, and talked about the United States in a state of emergency after 9/11. Public debate, it sometimes seemed, was displaced onto TV dramas. The slippage between debating a television show and debating a government’s policies and practices demonstrates the significance of TV dramas during the War on Terror.

After September 11, 2001, a number of TV dramas were created using the War on Terror as their central theme. Dramas such as 24 (2001–11), Threat Matrix (2003–4), The Grid (2004), Sleeper Cell (2005–6), and The Wanted (2009) depict U.S. government agencies and officials heroically working to make the nation safe by battling terrorism.11 A prominent feature of these television shows is Arab and Muslim characters, most of which are portrayed as grave threats to U.S. national security. But in response to increased popular awareness of ethnic stereotyping and the active monitoring of Arab and Muslim watchdog groups, television writers have had to adjust their story lines to avoid blatant, crude stereotyping.

24 and Sleeper Cell were among the most popular of the fast-emerging post-9/11 genre of terrorism dramas. 24 centered on Jack Bauer, a brooding and embattled agent of the government’s Counter-Terrorism Unit (CTU) who raced a ticking clock to subvert impending terrorist attacks on the United States. The title refers to a twenty-four-hour state of emergency, and each of a given season’s twenty-four episodes represented one hour of “real” time. Sleeper Cell was not as popular as 24, partly because it was broadcast on the cable network Showtime and therefore had a much smaller audience. While 24 lasted eight seasons, Sleeper Cell lasted two. Sleeper Cell’s story line revolved around an undercover African American Muslim FBI agent who infiltrates a group of homegrown terrorists (the “cell” of the show’s title) in order to subvert their planned attack on the United States.

This chapter draws from the many TV dramas but especially 24 and Sleeper Cell that either revolved around themes of terrorism or the War on Terror or included a few episodes on these themes. I begin by mapping the representational strategies that have become standard since the multicultural movement of the 1990s and discussing the ideological work performed by them through simplified complex representations. I then ask, If writers and producers of TV dramas are making efforts at more complex representations, how are viewers responding to them? Finally, I address the concerns expressed by various organizations regarding representations of torture on TV dramas.

Simplified Complex Representations

Simplified complex representations are strategies used by television producers, writers, and directors to give the impression that the representations they are producing are complex. While I focus on television, film uses these strategies as well. Below I lay out what I have found to be the most common ways that writers and producers of television dramas have depicted Arab and Muslim characters after 9/11. While some of these were used more frequently (and to greater narrative success) than others, they all help to shape the many layers of simplified complexity. I argue that simplified complex representations are the representational mode of the so-called post-race era, signifying a new era of racial representation. These representations appear to challenge or complicate former stereotypes and contribute to a multicultural or post-race illusion. Yet at the same time, most of the programs that employ simplified complex representational strategies promote logics that legitimize racist policies and practices, such as torturing Arabs and Muslims. I create a list of some of these strategies in order to outline the parameters of simplified complex representations and to facilitate ways to identify such strategies.

Strategy #1: Inserting Patriotic Arab or Muslim Americans

Between 2001 and 2009 television writers increasingly created “positive” Arab and Muslim characters to show that they are sensitive to negative stereotyping. Such characters usually take the form of a patriotic Arab or Muslim American who assists the U.S. government in its fight against Arab/Muslim terrorism, either as a government agent or as a civilian. Some examples of this strategy include Mohammad “Mo” Hassain, an Arab American Muslim character who is part of the USA Homeland Security Force on the show Threat Matrix; Nadia Yassir, in season 6 of 24, a dedicated member of the CTU;12 and in Sleeper Cell the lead African American character, Darwyn Al-Sayeed, a “good” Muslim who is an undercover FBI agent who proclaims to his colleagues that terrorists have nothing to do with his faith and cautions them not to confuse the two.13 In a fourth-season episode of 24, two Arab American brothers say they are tired of being unjustly blamed for terrorist attacks and insist on helping to fight terrorism alongside Jack Bauer.14 Islam is sometimes portrayed as inspiring U.S. patriotism rather than terrorism.15 This bevy of characters makes up the most common group of post-9/11 Arab/Muslim depictions. This strategy challenges the notion that Arabs and Muslims are not American and/or un-American. Judging from the numbers of these patriots, it appears that writers have embraced this strategy as the most direct method to counteract charges of stereotyping.

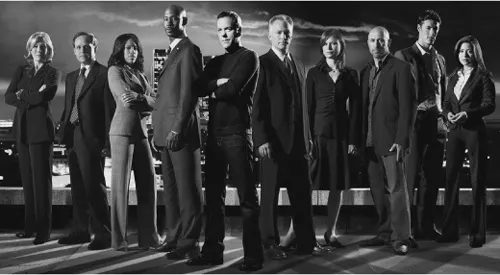

Figure 1.1. Strategies 1 and 6, the cast of 24, Season 4. Marisol Nichols, who plays Counter Terrorism Unit agent Nadia Yasir, is pictured on the far right (strategy 1). The multicultural cast (strategy 6) includes an African American president, Wayne Palmer, played by D. B. Woodside, pictured fourth from the left.

Strategy #2: Sympathizing with the Plight of Arab and Muslim Americans after 9/11

Multiple stories appeared on TV dramas with Arab/Muslim Americans as the unjust victims of violence and harassment (see chapter 2). The viewer is nearly always positioned to sympathize with their plight. In an episode of The Practice the government detains an innocent Arab American without due process or explanation, and an attorney steps in to defend his rights.16 On 7th Heaven Ruthie’s Muslim friend, Yasmine, is harassed on her way to school, prompting the Camden family and their larger neighborhood to stand together to fight discrimination.17 This emphasis on victimization and sympathy challenges long-standing representations that have inspired a lack of sympathy and even a sense of celebration when the Arab/Muslim character is killed.

Strategy #3: Challenging the Arab/Muslim Conflation with Diverse Muslim Identities

Sleeper Cell prides itself on being unique among TV dramas that deal with the topic of terrorism because of its diverse cast of Muslim terrorists. It challenges the common conflation of Arab and Muslim identities. While the ringleader of the cell, Faris al-Farik, is an Arab, the other members are not: they are Bosnian, French, Euro-American, Western European, and Latino; one character is a gay Iraqi Brit. Portraying diverse sleeper cell members strategically challenges how Arab and Muslim identities are often conflated by government discourses and media representations by demonstrating that all Arabs are not Muslim and all Muslims are not Arab and, further, that not all Arabs and Muslims are heterosexual. In addition, the program highlights a struggle within Islam over who will define the religion, thus demonstrating that not all Muslims advocate terrorism. For example, in one episode a Yemeni imam comes to Los Angeles to deprogram Muslim extremists and plans to issue a fatwa against terrorism.18 These diverse characters, and their heated debates for and against terrorism, indeed distinguish Sleeper Cell from the rest of the genre. But this strategy of challenging the Arab/Muslim conflation is remarkable in part because of its infrequency.

Strategy #4: Flipping the Enemy

“Flipping the enemy” involves leading the viewer to believe that Muslim terrorists are plotting to destroy the United States and then revealing that those Muslims are merely pawns for Euro-American or European terrorists. The identity of the enemy is thus flipped: viewers discover that the terrorist is not Arab, or they find that the Arab or Muslim terrorist is part of a larger network of international terrorists. On 24, Bauer spends the first half of season 2 tracking down a Middle Eastern terrorist cell, ultimately subverting a nuclear attack. In the second half of the season, we discover that European and Euro-American businessmen are behind the attack, goading the United States into declaring a war on the Middle East in order to benefit from the increase in oil prices. Related to this subversion of expectations, 24 does not glorify the United States; in numerous ways the show dismantles the notion that the United States is perfect and the rest of the world flawed. FBI and CIA agents are incompetent; other government agents conspire with the terrorists; the terrorists (Arab and Muslim alike) are portrayed as very intelligent. Flipping the enemy demonstrates that terrorism is not an Arab or Muslim monopoly.

Figure 1.2. Strategy 3, Challenging the Arab/Muslim conflation and representing diverse Muslim identities. DVD cover of Sleeper Cell.

Strategy #5: Humanizing the Terrorist

Most Arab and Muslim terrorists in film or on television before 9/11 were stock villains, one-dimensional bad guys who were presumably bad because of their ethnic background or religious beliefs.19 In contrast, post-9/11 terrorist characters are humanized in a variety of ways. We see them in a family context, as loving fathers and husbands; we come to learn their back stories and glimpse moments that have brought them to the precipice of terror. In 2005 24 introduced viewers to a Middle Eastern family for the first time on U.S....