![]()

Part I

The Meaning and Significance of Race in the Culture of Capital Punishment

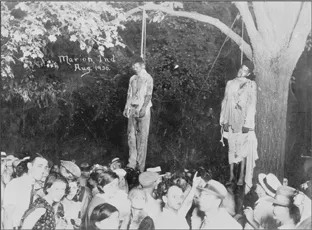

Lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith. August 7, 1930, Marion, Indiana. Without Sanctuary plate 31. Courtesy of the Allen-Littlefield Collection.

![]()

Chapter 1

Capital Punishment as Legal Lynching?

Timothy V. Kaufman-Osborn

I. Introduction

In the early morning hours of August 7, 1930, three African-American men, Tom Shipp, Abe Smith, and James Cameron, confessed to the murder of Claude Deeter, a 24-year-old white factory worker, and to the rape of his 18-year-old companion, Mary Ball. That evening, enraged by the sight of Deeter’s bloody shirt, which police had hung from a window in city hall, a band of local residents broke into the Grant County jail, overwhelmed Sheriff Jake Campbell and his deputies, and removed the three teenagers from their cells. After hanging Shipp from the window bars of his cell, they forced Smith to run through a gauntlet whose members tore off most of his clothing and then hanged him from the limb of a maple tree at the northeast corner of Courthouse Square. Returning to the jail, several men cut down Shipp’s body, carried it to the square, and, after hoisting his corpse alongside that of his friend, attempted but failed to light a fire aimed at incinerating both. James Cameron was spared only because someone, possibly Mary Ball’s uncle, or perhaps the head of the local American Legion, climbed atop a car parked on the square and insisted that he was innocent, thereby affording Sheriff Campbell an opportunity to return Cameron to his cell. Sometime after midnight, but before daybreak, on Friday, August 8, when the bodies of Shipp and Smith were cut down, local photographer Lawrence Beitler captured the scene in the heart of downtown Marion, Indiana.1

Sixty-four years later, on December 5, 1994, local members of Amnesty International organized a protest against the imminent execution of Gregory Resnover, an African-American convicted of conspiring to murder and then murdering a white Indianapolis police officer in 1980. Standing on the steps of the Indiana Statehouse, Resnover’s attorney, Robert Ham-merle, noted that even the former chief deputy prosecutor for Marion County now agreed that the trial record reviewed by the state Supreme Court contained numerous factual errors, including the statement that Resnover’s fingerprints had been found on two weapons fired at the officer. Moreover, Hammerle proceeded, Resnover’s original attorney had failed to introduce any witnesses during the sentencing phase of the trial, and had later been found incompetent by the state’s highest court after it reversed the conviction of the one other individual he had represented in a capital case: “In the old South,” Hammerle concluded, “they didn’t pretend to give you due process. We’re pretending to give Gregory Resnover due process and that makes this death more diabolical.” Resnover’s three brothers then read from a letter recently sent by Gregory to several state officials: “Society as a whole needs to be certain that you are convinced beyond doubt that racism played no role in my case. Show them that you are certain.” Finally, to drive home their brother’s point, Kevin, Steve, and Dwight held aloft an enlarged version of the photograph taken by Lawrence Beitler in 1930.2 Four days later, Gregory Resnover was executed by means of electrocution at the Indiana state prison in Michigan City.

The purpose of this essay is to explore the sense and adequacy of the charge that was implicitly leveled when Gregory Resnover’s brothers displayed the photograph of Tom Shipp and Abe Smith. As I understand it, that accusation contends that because racism continues to taint the criminal justice system, the contemporary execution of African-Americans and, more particularly, African-American men is akin to the lynchings that occurred throughout the United States, but especially in the South, in the era roughly delimited by the end of Reconstruction and the onset of World War II. As Stephen Bright, director of the Southern Center for Human Rights, puts the point: “The death penalty is a direct descendant of lynching and other forms of racial violence and racial oppression in America.”3 To the extent that this indictment is accurate, it renders problematic the tale many of us would like to be able to tell ourselves about America’s consolidation of the due process protections that are said to secure a categorical distinction between the extralegal violence of lynching and the legal violence of capital punishment.4 There is, I grant, good reason to reject this Whiggish tale, and I will indicate why that is so in what follows. Yet, it is equally true that appropriation of the category of lynching to make sense of the contemporary practice of capital punishment, as with all categories, conceals as much as it reveals. Specifically, identification of these two practices draws attention away from the ways that capital punishment, as now conducted in the United States, occludes what lynching accomplished all too well. Whereas lynchings visibly marked the bodies of its victims as black and so reconsolidated the color line that was indispensable to the reproduction of racial subordination, key elements of the contemporary practice of capital punishment veil that line and so render its contribution to racial subordination more difficult to apprehend and so to contest.

In section II, I establish a theoretical context for my analysis by appropriating an argument advanced by Charles Mills. That argument suggests that the liberal social contract of the United States has always been under-written by what Mills calls “the racial contract,” and hence racist practices, including lynching, are not aberrations from this nation’s true principles but, rather, manifestations of its abiding commitment to sustain the conditions of racial exploitation. In section III, I advance a very selective history of lynching following Reconstruction. Here, my inquiry is confined to two aspects of this practice: first, in part A, the character of many lynchings during this era as highly ritualized public spectacles, which, I argue, transformed formally emancipated African-American men into racially marked and hence resubordinated subjects of white power; and, second, in part B, the permeability of the boundary between, on the one hand, the bands of white citizens who typically instigated such lynchings and duly authorized agents of law enforcement, on the other. In the penultimate section (IV), I inquire into the usefulness of the category of lynching as a way of articulating the contemporary relationship between race and capital punishment. In the first part of that section, corresponding to part A of section III, I ask how capital punishment, now conducted not as a public ritual but as a rationalized administrative procedure hidden from view, constructs a body that better coheres with the imperatives of the liberal social contract, but in doing so masks its participation in the replication of racial subordination. In the second part of that section, corresponding to part B of section III, I suggest that capital punishment, as practiced today, better meets liberalism’s requirement that the official realm be neatly segregated from the unofficial, but in doing so once again obscures the state’s complicity in the constitution of racial power. Finally, and very briefly, in the conclusion (V), I explain why my argument suggests the problematic character of any effort to remedy the racist character of capital punishment from within the confines of liberal political doctrine.

II. The Racial Polity

To establish a theoretical context for this inquiry, I begin with a schematic account of an argument advanced by Charles Mills in The Racial Contract and subsequently elaborated in Blackness Visible. The central premise of Mills’s argument is that “the United States has historically been, and in some ways continues to be, a racial polity, a political system predicated on nonwhite subordination.”5 On this account, the liberal social contract implicit in the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and elsewhere has been and still is underwritten by a racial contract whose general terms can be read off legally codiffed institutions (e.g., slavery), formal government acts (e.g., Jim Crow laws), unofficial modes of official conduct (e.g., racial profiling by law enforcement officers), informal practices in the private sphere (e.g., patterns of residential segregation), theoretical discourses (e.g., biologistic accounts of racial inferiority), pernicious stereotypes (e.g., regarding the criminal propensities of young black men), and so on. The central purpose of the racial contract is to secure and ratify limitations on the freedoms, rights, and privileges of those whose exploitation is a condition of the freedoms, rights, and privileges of the superordinate group. Racial domination, on this account, cannot be understood as an unfortunate departure from a norm of universal equalitarianism, for, from its very inception, the United States has been “a system for which racially determined structural advantage and handicap are foundational.”6

Within a liberal political order formally committed to an ideal of equal citizenship, ratification of such subordination has been accomplished, Mills argues, through generation and ongoing activation of a distinction between “persons” and “subpersons.” In the United States, perhaps the most obdurate materialization of this distinction has been that between white and black, where racial identity is understood “as a politically constructed categorization,” “the marker of locations of privilege and disadvantage in a set of power relationships.”7 The racialized category of subperson, Mills continues, has been differently defined at different moments in American history, depending on whether its members have been identified with the nonhuman (e.g., the animal); the innately inferior but human (e.g., the “colored,” who, by nature, are lazy and shiftless); the permanently immature but human (e.g., the Negro as child); the formally equal but nonwhite human (e.g., the “persons of color” through reference to which whiteness is known as such); and so forth. No matter what its exact formulation, however, members of the category of persons are considered full citizens, and, as such, deemed eligible for uncircumscribed participation in the mythic contract that founds a liberal political order, and so full civil status in that order once created. Subpersons, in contrast, are either excluded altogether from participation in that contract, as under slavery, or relegated to an inferior, marginalized, or suspect status that compromises their standing as members fully eligible for the freedoms, rights, and privileges enjoyed by persons.

On Mills’s account, the disposition of American history may be understood, at least in part, as a product of the relationship assumed between the social and racial contracts at any given moment in time. As I have already indicated, the wrong way to construe this relationship is to think of racial subordination as a regrettable deviation from the universalistic principles of the social contract, and to conclude that, as such, this form of oppression is destined to disappear as liberalism progresses toward complete realization of its essential ideals. That noted, to the extent that the category of subpersons has sometimes been subject to challenge by its members and their allies, to the extent that the boundary dividing this group from that of persons has sometimes proven permeable, to the extent that the liberal state has sometimes been compelled to acknowledge and respond to the tension between the formal equality mandated by the terms of the social contract and its complicity in maintaining the conditions of the racial polity, to that extent has the relationship between these two contracts, and so between black and white, proven susceptible to rearticulation. “The Racial Contract,” Mills writes, “is continuously being rewritten to create different forms of the racial polity,” which means in turn that “the effective force of the social contract itself changes, and the kind of cognitive dissonance between the two alters.”8

To illustrate, in the South prior to the Civil War, so long as the enslavement of blacks was codiffed in law, so long as white supremacy was openly proclaimed, there was little reason to doubt that the social contract applied to whites only, and so the relationship between it and its racial counterpart proved relatively unproblematic. However, as I shall explain in greater detail in the following section, when that structure of domination lost its de jure character, when political and civil rights were formally extended to emancipated male slaves, the category of persons was no longer officially coextensive with that of whites. Consequently, obfuscation of the tension between an abstract, i.e., formally color-blind, conception of citizenship and various institutions that actively participated in the construction of “colored” individuals required a different and less transparent set of practices, legal and otherwise. Barely less transparent than slavery, for example, were those post-Reconstruction laws, which, dispensing with any façade of statutory neutrality, expressly excluded blacks from participation in certain practices definitive of citizenship (e.g., jury duty). Somewhat less transparent were the various mechanisms devised in the post-Reconstruction South to disenfranchise blacks without technically violating the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, including poll taxes, grandfather clauses, and literacy tests. Through these means, the neutrality of the liberal state was formally upheld, as demanded by the social contract, without in any significant way challenging the racial polity.

Today, re-creation of the racial contract in the United States requires ongoing negotiation of the tension between the social contract’s formally color-blind principles and the color-coded practices, which, although necessary to white superordination, must now do their work in a state of relative (but not complete) invisibility. The capacity of such invisibility to veil the workings of the racial contract is enhanced, Mills argues, by the “epistemology of ignorance”9 that is often evinced by those who benefit from the racial contract but whose self-conception renders them unable to recognize, let alone to acknowledge, that they do so. This epistemology can assume many forms, including racially coded language (e.g., talk of “wel-fare queens”), statutory proxies for more direct forms of racial oppression (e.g., longer sentences for crack as opposed to powder cocaine users), hostility to government policies on the grounds that they are harmful to their intended beneficiaries (e.g., neoconservative opposition to affirmative action), and, perhaps most significantly, obfuscation of the distinctive history of African-Americans by formally assimilating them to the general category of persons and so denying that the category of subperson, no matter how unlike the form it assumed under slavery or following Reconstruction, remains a living reality: “The danger of the universalist and colorless language of personhood is that it too easily slips over from the normative to the descriptive, thus covertly representing as an already achieved reality what is at present only an ideal, and failing to register the embedded structures of differentiated treatment and dichotomized moral psychology that ‘subpersonhood’ captures.”10 The epistemology of ignorance is most effective and, as Gregory...