![]()

1

Columbian Exchange

The winter had started when the Pilgrims, religious exiles from both England and Holland, arrived at the Massachusetts coast on November 11, 1620. The Mayflower had been at sea for sixty-five days and no terrible diseases had seized them during the crossing. Dr. Samuel Fuller, the ship’s surgeon had lost only one passenger and a seaman who had been sickly from the beginning, leaving one hundred men and women passengers and forty-seven crewmen. While anchored and deciding where to go from this point, a few more passengers and three of the remaining crew died. A decision was made not to proceed to Virginia, their original destination, but to settle in what had long been a fishing area for many Europeans—Portuguese, English, Italians, French, and possibly others since the 1480s, long before Columbus. Massachusetts was not an unknown land and had been mapped by John Smith a few years before the arrival of the Pilgrims. The Pilgrims would be the first Europeans to successfully plant a settlement in New England. A small party left the ship and began to explore the area known as Cape Cod.

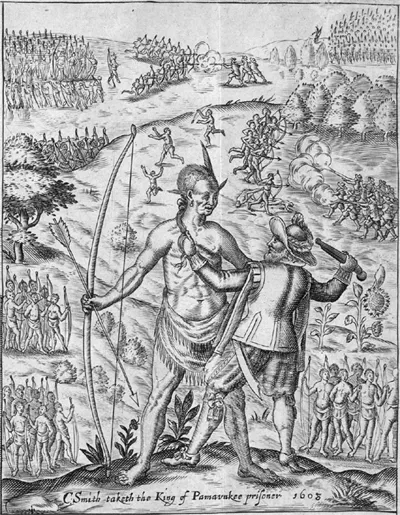

In this illustration of John Smith’s encounter with Opechancanough, the Pammunkey chief in Virginia in 1608, we see the Indians as stronger, healthier, and more muscular than the English. Here Smith is demonstrating his mastery over his much taller captive. Most commentaries at the time of first contact describe the Indians as healthy, a condition that would change dramatically shortly afterward. From John Smith, General Historie of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles (1624). (Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, STC 22790)

Other Europeans who had explored along the northeastern coast had failed to create any permanent colonies. Giovanni de Verrazzano, an Italian acting for the French king, traded with the locals in 1523, but his crew was driven away, he reported, by a large number of hostile Indians. About eighty years later Samuel de Champlain visited Cape Cod in the hopes of setting up a French base, but the thickly settled villages discouraged him. Well armed and with large populations spread along the New England coast, the Indians successfully prevented any permanent European settlements, accepting only the sojourners, fisherman, who came for a few months, fished and traded for furs, and then went home. In 1614 John Smith appeared on the coast but soon left after arranging for his lieutenant Thomas Hunt to dry the fish they had caught before returning to England. But Hunt antagonized the locals by kidnapping some of the Native Americans; he was initially driven off but retained a few of his victims to take back to England, including one man named Tisquantum (better known as Squanto) of the Wampanoag tribe. Shortly afterward, Sir Fernando Gorges tried to found an English community in present-day Maine, but his group too was driven off by the Natives who, after the experience with Hunt, considered Europeans to be extremely dangerous people. In the following years, others who landed on the soil found the Indians violently hostile, determined to prevent any more foreigners from appearing on their shores. Sometime during 1616 a shipwrecked French ship was attacked; the Indians killed some of the crew and others were carted off to replace those men lost to the English. Shortly afterward, another French ship appeared in the vicinity of Boston. It was set afire and everyone on board was killed. European settlement was not wanted and was easily discouraged by the large number of native people in the area.

Unwilling to be intimidated by potential threats from the local inhabitants, the Pilgrims sent a small group of armed men to search the land and find a place to settle. They saw a few Indians who ran away but did not come across the large number of thickly settled villages described by others, nor were they threatened in any way. In one deserted village, the scouting party saw tools scattered and fields cleared but no sign of inhabitants. They dug up some graves and found a few objects, which they took back to the Mayflower, and a cache of corn that could be used for seed. On December 16, 1620, the passengers disembarked and began to build houses and a fort for a permanent town on the site of the old village. But where were the great numbers of Indians noted by earlier visitors? The Pilgrims decided that God must be on their side and had cleared the land for His chosen people.

Without assistance from the natives, the Pilgrims suffered terribly that first winter. Insufficient food had been brought on the boat, and there was little nourishment to be had from the land before the spring. Between December 16 and the end of the following March forty-four more Pilgrims died, and the crew lost half their number to a variety of illnesses. Dr. Fuller blamed the deaths on scurvy, a nutritional deficiency that was not recognized as such at the time but was believed to be an infection like other diseases. A handful of Indians watched their suffering from a distance but did not approach except for the theft of some tools. More Pilgrims arrived that spring of 1621, further stressing the food resources. But none left to go home on the returning Mayflower. Their decision to stay was born of their determination to establish a Godly community separate from the taint of either Dutch influence or that of the English Church in spite of the deprivations in the wilderness.

The mystery of the missing Indians was soon solved; in the middle of March 1621 the Wampanoag chief, Massasoit, sent an emissary, Samoset, an Abenaki from Maine with some skill in English, to talk to the Pilgrims. Samoset had recently arrived in Massachusetts brought from Maine by Captain Thomas Dermer who was sailing along the coast in 1619. On his arrival Samoset noted that what had once been a populous region was now “utterly void” because, he told the Pilgrims, of a terrible sickness that had killed off many of the local people. The Pilgrims were given more details of the missing population after Massasoit arrived with Squanto, one of Captain Hunt’s 1614 captives who had been able to return to Massachusetts on Dermer’s ship from London. When he returned after five years, Squanto said that he found his village deserted and everyone dead.

As the story was pieced together, the Pilgrims learned that sometime between 1616 and 1617 an unidentified plague had visited the Indians and eventually killed close to 90 percent of the coastal population. Squanto’s kidnapping by Hunt in 1614 had inadvertently saved his life. Charles Mann estimates that the Wampanoag confederacy included as many as 20,000 people in 1614 but was reduced to 1,000 by 1619 after the epidemic had run its course. That left Massasoit, the surviving Wampanoag chief, in a dilemma. He had only sixty men left to fight his enemies the Narragansetts, tribes that had not been affected by the disease. His gods, he believed, had abandoned the Wampanoag, and now he was forced to accept the English as allies. Taking advantage of Squanto’s English skill, Massasoit offered friendly relations, trade, and assistance in return for loyalty and support in war. The Pilgrims, in turn, were confirmed in their belief that God had cleared the land for them by bringing a pestilence to the Indians, providing additional incentive for them to remain to facilitate the “New England Zion.” According to John Winthrop, God had cleared the land to “make room” for them. Such smugness did not bode well for the remnant of the Indian tribes of the area. But in 1620 Massasoit was desperate for assistance, and the Pilgrims saw the benefit of allying with him.

The nature of the epidemic that had led the Indians to accept the presence of the Pilgrims is still a mystery. It was not unusual for a variety of illnesses originating in the Old World to appear among the Native Americans before any direct contact with Europeans. This would not be the first time for such a thing to happen. The disease that had decimated the New England coast peoples may well have started in the more northerly French settlements in Canada. Alfred Crosby in his Columbian Exchange notes a commentary in the Jesuit Relations of 1616 of an Indian complaint: since the French had arrived “they [the natives in Canada] are dying fast and the population is thinning out.” Since trading with the Europeans, Indians lamented that they “have been more reduced by disease.” Whatever the disease was in Canada could easily have spread south during warfare or as a result of trade. Or the disease may have been present on one of the European ships, either French or English, that had appeared along the coast in 1616. A captured Frenchman may well have been sick at the time.

But what was the disease? There are few eyewitness accounts of the epidemic in New England; to all it was an unfamiliar plague that had ended as mysteriously as it had begun. Some observers described skin marks or pox on those who lived. The Gorges expedition in Maine at the beginning of the epidemic in late 1616 were told that sufferers began with a headache as a major symptom followed by scabs and a yellow coloring of the skin. The latter commentary has led some scholars to the idea that it might have been hepatitis, but that has been recently discounted. Nor was it yellow fever because the weather was too cold for the aegpti mosquito to survive the winters, and there is no mention of ships from Africa, the source of the disease. Measles, in turn, would not have caused such a high mortality, although it may have accompanied the more virulent disease. Nor did crowd diseases that require dense populations in close quarters (like the bubonic plague or typhus) fit the conditions of Native life. The most convincing analysis of the situation comes from Timothy L. Bratton. After considering all of the possibilities based on the timing, the extensive mortality, and the nature of the symptoms, Bratton concluded that it was most likely smallpox, that scourge of the Indian population since 1518 when it first appeared in the West Indies.

Smallpox can be caused by any of nine types of the variola virus, with symptoms that range from merely flu-like aches to the most lethal type: runny scabs that cover the entire body including the soles of the feet and palms of the hands and could lead to massive stripping of the epidermis. Blindness was often the result for those who survived the worst type. The fatality rate could vary between 7 percent (in London in the seventeenth century) to 15 percent (Boston in 1721) and 30 percent (Scotland in 1787). Elizabeth Fenn estimates that the fatality rate among Natives was much higher, closer to 50 percent and the rate of infection more than 80 percent. A disproportionate number of the very young and the very old died from the disease. In addition to age, survival also depended on nutritional status or pregnancy. Possibly 75 percent of pregnant women aborted. During the winter Indians often suffered from lack of food and that may have contributed to the high death rate during the cold months of 1617 and 1618 when sustenance was especially scarce.

Smallpox is a disease that can sustain itself over long periods of time within a community and just as easily spread to neighboring groups as a result of social contact or during warfare. It is easily communicated from person to person from droplets in the air, from the urine of an infected person, or from the fluid from unhealed skin lesions. In addition, the virus can live outside the human body for weeks on clothing or other inanimate objects that harbor the scabs. A long incubation period means that the infected person can mingle with the well for ten to fourteen days before knowing that he or she is sick. The first symptoms are like the flu—headache, fever, backache, nausea, and a general malaise. After four days sores usually appear in the mouth, throat, and nasal passages and then on the surface of the skin, including the face forearms, neck, and back, causing excruciating pain. Sometimes the pustules run together or turn inward, hemorrhaging under the skin, which, according to Timothy Bratton, may have given the impression of yellowish skin. A secondary bacterial infection is also possible. Death is usually after ten to sixteen days of suffering but can sometimes occur before the rash appears. The sick person, however, remains contagious until the last scabs falls off, sometimes a month after the first appearance. It is quite possible that Natives carrying gifts in blankets or other containers also carried the disease with them as they visited friendly tribes. The long incubation period and ease of communication thus fit the conditions of the Wampanoags in 1616. The extraordinarily high fatality rate of 90 percent is a different problem that requires explanation.

Because smallpox was a new disease in the Western Hemisphere, no one in America had any acquired immunity from a previous bout. The same circumstances applied to a host of diseases that were taking a devastating toll on Indian life: measles, typhus, typhoid fever, diphtheria, influenza, plague, whooping cough, and chicken pox, among others. Such diseases began in the Old World through the exchange of microorganisms between humans and domesticated animals. Smallpox, for instance, is thought to have evolved from a cattle or horse virus or one that affects camels. Bovine rinderpest became human measles in the same way that avian influenza became human influenza. What was missing from the Native American environment were the “crowd” diseases from microorganisms that needed animal hosts when not circulating among humans. Whatever herd disease immunities Indians may have had before the migration across the Bering Strait from Asia to Alaska (about 15,000 years ago) were lost when the cold killed off many of the germs, infected people died off, and the microorganisms no longer had hosts to maintain them. Such organisms died quickly outside the human body. Eurasians and Africans continued to live in close proximity to livestock and to exchange infections with the animals. But Native Americans had close contact with few animals and did not herd livestock. The New World had no cows, horses, or camels, and very few other domestic animals.

Old World people had adjusted to these diseases both socially and biologically to moderate the effects. There was always a proportion of the population, especially the adults, that had some immunity during an epidemic and could care for the sick. People had learned ways of protecting themselves against spreading the contagion through isolation and quarantines. Centuries of experience with smallpox had taught Old World societies that only those who had suffered a previous bout of that illness were safe from the contagion. Smallpox was a common affliction in populated areas in Europe and the British Isles; nearly all urban children caught it and were either soon dead or immune. American Indians had none of those advantages. Because they were a “virgin population” in the case of many bacteriological and viral diseases, adults were as likely as children to become sick. Their medicine provided no protection and may have made matters worse through practices that spread the disease. There appeared to be no concept of contagion in Indian culture. The healers and the shaman often played out their rituals in the presence of many people in the community who were then exposed to the disease and could carry it back to their own families.

Native medicine, like that of the seventeenth-century Englishmen, was closely identified with religion. Sickness was ascribed to offended or malevolent spirits that had to be appeased. The function of the shaman was to divine who was causing the trouble and either propitiate the spirit or find a friendly spirit to intervene. Thus the medicine man, in the presence of the community, used a variety of paraphernalia along with incantations, dances, the sprinkling of substances, and bloodletting to remove the poison introduced by those spirits. Spiritual healing was supplemented with herbal concoctions, many of which were eventually borrowed by the Europeans: sassafras, ginseng, ipecac, and snakeroot entered the pharmacopeias and became important herbal exports to Europe. European observers thought many of the treatments were effective even though they condemned the spiritual elements as witchcraft. For fractures Indians made splints, used moss and other materials to stop bleeding, and treated rheumatic problems with sweat baths followed by cold-water plunges, massage, and aromatic fumigation. There was little attempt at surgery except when used as torture on prisoners. However effective the Native medical practices were for traditional ailments, they could be harmful when used for European diseases.

There are innumerable conditions that can influence the way a body reacts to a disease and determine how dangerous it could be. Inadequate nursing care, poor nutrition, inappropriate healing customs, mutation of the virus, previous contact with the disease, or genetic factors can all play a role in an epidemic and influence the mortality rate. Native healing practices that sometimes called for a sweat bath followed by a plunge in cold water was dangerous for those with smallpox. Many times entire families were laid low together. When a large number of people became sick at the same time, there were too few of the uninfected to care for them. Nor were there enough adults to tend to the gardens or cook the food for either the sick or the young, contributing to the nutritional deficiencies. Alfred Cosby points out that a disproportionately large percentage of Native Americans aged fifteen to forty died during that first century of contact leaving children neglected and food and water procurement precarious, all of which contributed to the deadly results. When faced with such a catastrophe, apparently healthy Indians often ran away from the tribe in panic and unknowingly carried the virus to others, thus spreading the disease far and wide. Moreover, such diseases often became more virulent when transmitted by a family member (rather than by an unrelated person) and many in the tribes were closely related. All such conditions probably prevailed in New England between 1616 and 1619. One indication of how new the disease of smallpox was to the Americas was in its very virulence. A disease new to a population may mutate, a process known as genetic shift, and will usually be more dangerous and have more painful symptoms in that primary form. In time it will become less virulent. If it kills off all its hosts, it will not be able to survive; thus it becomes a milder disease to keep the virus alive.

Smallpox had been around in Europe for many centuries. It has an even older history in the East: there is evidence in Egyptian mummies from 1200 BCE, and it devastated the Roman army in 164 CE. It is suspected that the virus became more virulent in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Europe and that the American Indians were infected with a more dangerous mutation than had been usual in the past. Nonetheless, the fatality rate and the symptoms among New World peoples was worse than experienced elsewhere. The mortality surpassed the deaths from the plague when it was a new disease in Europe in the fourteenth century.

For reasons that have recently come to light regarding the genetic makeup of Native Americans, we now suspect that they were innately more susceptible to contagious diseases like smallpox and measles than were Europeans and Africans. Charles Mann points out that Indians come from a small gene pool and, because of isolation from communicable disease, lacked most of the special molecules inside human cells that make it possible to recognize and attack dangerous viruses. European immune systems, on the other hand, with a more diverse genetic background, have a greater ability to identify and therefore attack harmful invaders. Long contact with such viruses and bacteria shaped immune systems to find and counter many contagious diseases, ultimately leading to genetic changes that were handed down in the DNA of offspring. Even unexposed Europeans, those who had been isolated from contact with smallpox, were more likely to ward off the worst symptoms and had a better chance of survival than Native Americans. In fact, Native Americans do not lack such molecules but have fewer of them inherited from their relatively disease-free ancestors.

The original gene pool of Native Americans was small from the beginning. Successive waves of migrants from Asia came from related peoples in the Old World—almost all were of the “O” blood type with few variations in the mitochondrial DNA, a quality inherited matrilineally and often used to trace genealogy. A small group of later migrants from Asia were of the “A” blood type, but they did not move far beyond central Canada. However, there is no B or AB blood type among any of the early American Indians. Moreover, in physical characteristics, Indians are fairly uniform from the northern part of North America to the tip of South America: black hair, brown eyes, high cheek bones, with small variations in skin tone and body shape. There is nothing resembling the genetic differences seen in the Old World from the fair-skinned, blond, blue-eyed northerners to the black skin of sub-Saharan Africans with dark eyes and dark hair; and variations in body type from the diminutive pigmies to the more than the six-footers in central Africa. The lack of genetic variation among American Indians was sometimes beneficial. For instance, Indians lack the genes of Old World people that predispose them to cystic fibrosis, asthma, or some kinds of diabetes, but it also meant that they lacked the genetic qualities that provided immunity to certain communicable diseases. Thus, contact with Europeans was a disaster waiting to happen.

Nor all historians agree with Charles Mann that genetic factors explain what happened to the Native American population. They do not deny the presence of smallpox, measles, or the variety of respiratory ailments in a population that had had no contact with those diseases, but some scholars put a greater emphasis on environmental factors. David Jones, for instance, insists that the cause was a lack of adaptive immunity and not from genetic characteristics. He argues that the emphasis on genetics as the major cause of depopulation removes the responsibility from human behavior and “deflects attention away from moral and political questions.” Instead, Jones focuses on a combination of social, cultural, and environmental factors, more than the immune factors, to explain the devastation. For example, when everyone in a tribe fell sick at the same time, there was no one to comfort or take care of them. Many diseases appearing at the same time also took its toll. Smallpox victims become vulnerable to respiratory problems as well as measles. Measles in turn leaves its victims open to other diseases such as tuberculosis. Malnutrition also increases susceptibility to infection, and Jones notes the archeological evidence of malnutrition among American Indians before 1492, especially in Mexico and the Andes. In New England, colonization introduced a host of damaging “ecological chan...