![]()

1

The Irony of Acculturation

In the decades that surrounded the turn of the century, America faced a crisis of identity. To many Americans, achievement of social and cultural unity seemed more imperative than ever. The still recent Civil War had pitted citizens against one another in the bloodiest battles the nation had ever experienced. The rise of industrialization had sparked the movement of thousands into the cities. Others had poured into the western territories seeking greater opportunities. In the west, newcomers faced off with Native Americans in wars for land and cultural domination. Emancipation and citizenship laws opened new opportunities, and renewed conflicts, for African Americans in both the South and the North. Waves of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, Asia, and Ireland added diversity to all aspects of society. This diversity also caused considerable anxiety for “old stock” Americans who feared the transformative power these changes and people would bring.

Attempts to reassert a unified American identity took on various forms. Nativists sought to curtail the entrance of “outsiders” who did not match a narrow definition of the true American citizen. Others offered these cultural and geographic foreigners settlement houses and social welfare programs, hoping to uplift them with training in practical skills and American cultural values. Progressives’ primary tool of assimilation and acculturation, however, was the public school. Promising to instill an education fitted to modern needs, schools not only instructed young pupils in rudimentary academic subjects but also emphasized unity through such common values as democracy, industry, and civic responsibility. Of utmost importance, schooling promoted the use of a common American language— English.

Oralism—training in speech and lipreading—became the principal means of pressing this agenda on the Deaf community. Newton F. Walker, superintendent of various deaf schools during his long career, claimed that deaf people who could speak English “have the viewpoint more largely of the great mass of people among whom they must live.… They are broader in their vision.”1 From the oralist perspective, the residential schools that educated deaf people had given rise to a separate, distinct Deaf culture built upon the foundation of sign language. In response, oralism, in its strict application, sought to replace signed communication altogether. Graduates of these schools sought not only to limit the advance of oralism but also to subvert what it represented: an attempt by hearing individuals and mainstream society to stigmatize, if not eradicate, a separate Deaf identity. Thomas Fox’s life highlights this conflict of cultures.

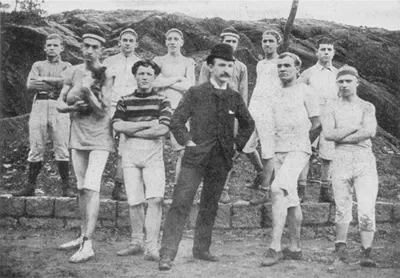

Born in New York on November 16, 1859, the seventh child of Irish and Scottish immigrants, Fox, at the age of ten, became deaf after contracting spinal meningitis. In 1874, his parents enrolled him in the New York School for the Deaf (the “Fanwood” school). There, Fox claimed, “a marvelously new life opened itself.” At Fanwood, he learned sign language, made lasting friendships, and began to claim his identity as a Deaf person. Although he was able to vocalize articulately, he recognized firsthand the impossibility of mastering lipreading. Concerned that communication barriers would undermine his ability to learn, he chose in 1879 to enter Gallaudet College, rather than a mainstream university.2

Shortly after completing his freshman year at Gallaudet in 1880, Fox attended the first meeting of the National Association of the Deaf. Politicized by the attacks on Deaf culture and common prejudices against Deaf people, he became an outspoken advocate of traditional Deaf values. Like many of his peers, Fox encouraged the preservation of deaf residential schools, the employment of Deaf teachers, and the use of signed communication in the classroom. His career choices reflected his commitment to preserving Deaf culture. Shortly after graduating from Gallaudet, he returned to his alma mater in New York, where he remained for fifty years. Beginning as a teacher for the slowest students at Fanwood, he quickly ascended to teach the highest classes. He then became the senior assistant to the principal and, in 1932, the principal of the Academic Department. Even after his retirement as a teacher in 1933, Fox maintained close ties to Fanwood, including service as the editor of the school’s prestigious newspaper, The New York Journal of the Deaf, a position he held until his death in 1945 at age 85.

Thomas Francis Fox and athletes from the Fanwood School, 1889–90. Gallaudet University Archives.

Fox insisted on the legitimacy of Deaf culture and on the equal status of Deaf citizens. As a leader in the Empire State Association of the Deaf, he spearheaded the campaign to transfer schools for the deaf from the jurisdiction of state welfare and charity departments to departments of education. He frequently drew attention to this issue at national and state Deaf conferences, as well as at professional meetings of deaf educators and administrators. Like most members of the Deaf elite, he staunchly advocated a combined method of teaching. That plan offered deaf students courses taught in sign language, as well as instruction in lipreading and speech. In one of his many public commentaries about communication methods in schools, he wrote:

To the occasional cry for a “speech atmosphere” in schools employing the combined system, we would modestly, but none the less emphatically, suggest that the suppression of the sign language in the playrooms and playgrounds of deaf children is a measure of cruelty, opposed to their instincts, inimical to their happiness, and detrimental to their moral and intellectual development. And where there is total separation within an institution of one class of deaf children from another, except as a temporary means of discipline, or in cases of infectious disease, it is devoid of all religious, moral or social sanction.3

His success as an educator attested to the benefits of the combined approach. Because of Fox and other deaf advocates, the schools continued to use that method.

By the early 1900s, educators, policymakers, and medical professionals increasingly likened Deaf people, the vast majority of whom were born and raised in America, to foreigners. Like immigrants and Native and African Americans, Deaf people faced increasing pressure to assimilate more fully into mainstream society. But, for Deaf people more than other “outsiders,” the schooling experience caused their perceived and real marginality.

The evolution of deaf schools had produced an ironic result: the intent to integrate Deaf people into hearing society by enrolling them at residential schools instead made possible the rise of a separate, strong Deaf culture. Before the founding in 1817 of the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, deaf people in the United States lived within an inaccessible hearing world, separated from their own kind. Early-nineteenth-century educators, who were often ministers, intended to assimilate deaf people into Christendom by giving them the ability to read the Bible. By the Progressive era, educators of the deaf had extended this goal, seeking to assimilate Deaf people into mainstream (hearing) America. The rhetoric of educators frequently suggested attempts either simply to absorb or to control Deaf students. In that respect, hearing educators of deaf people pursued objectives that paralleled the goals of educators of ethnic minorities and new immigrants. As Theodore Roosevelt succinctly noted, “We have room for but one language here, and that is the English language; for we intend to see that the crucible turns our people out as Americans, of American nationality, and not as dwellers in a polyglot boardinghouse.”4

From School Ground to Battle Grounds

The Deaf community combated strict oral teaching in schools by implementing or preserving a combined communication method that incorporated both sign language and oral communication. Deaf people tirelessly fought to maintain their role in deaf education. Most advocates for the traditional Deaf values of communicating in sign language and employing Deaf teachers gained limited acceptance from their intellectual critics and from the broader society. In many ways, the battle over the schools proceeded by attrition. As oralism gained ground, Deaf adults became marginalized from the schools, a traditional “place” of their culture. Deaf people like Thomas Fox not only resisted this marginalization; they managed to participate in teacher qualification programs, influence faculty and administrators, increase the use of sign language in schools, and transmit positive cultural views of Deafness within the schools. In doing so, they broadened their strategies to defend their culture, fostered greater unity within the Deaf community, and maintained a separate communal identity.

The debate over communication methods long predated the establishment of the first school for the deaf in America. Ancient philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle pondered whether deaf people could learn speech or could process knowledge. By the sixteenth century, some deaf pupils in Europe were receiving instruction through sign language.5 In mid-eighteenth-century France, sign-based education became well established and began to spread to other European countries. Meanwhile, private tutoring in late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century England and Germany evolved into schools that implemented oral and lipreading techniques. In America, most schools founded between 1817 and the 1860s adopted the French method of sign-based teaching. No classes formally taught signs; teachers and students simply used them as the language of instruction and communication. As a result, the language and the method became a central part of a developing Deaf culture. The schools fostered a common sign language across the nation. In addition they provided Deaf people with a self-contained and supportive environment. New “places” for Deaf people sprang from the schools, beginning with alumni associations, churches, and Deaf publications. In 1864, Deaf people gained the opportunity for advanced education with the establishment of Gallaudet College.6

Thus, by the mid-nineteenth century, Deaf cultural self-awareness was established and expanding. In the late nineteenth century, critics’ growing concern over this separate Deaf culture inspired a unified attack on the community. Led by the charismatic and influential Alexander Graham Bell, oralists argued for the “restoration” of Deaf people into mainstream American society, a goal viable, they said, only through training in speech and lipreading.

During the decades around the turn of the century, several other cultural developments created a more hospitable environment in the United States for pure oralism. Progressives sought not only the reform of education but also the reform of students through education. Oralists and other educational reformers considered hearing teachers to be the best role models to help integrate Deaf students into mainstream society. At the same time, advances and increased interest in biology and other scientific disciplines in the early 1900s generated a movement for a “new education”— one that leaned heavily toward the pure and the applied sciences. Proponents of this “new education” viewed the objective of education as preparation for life. They emphasized the need for vocational training and practical subjects such as mathematics so that Deaf students would have a place in the adult world. For all of these reasons, by the twentieth century, oralism began to displace sign language as the primary teaching method used in American schools.

Oralists drew on other contemporary concerns to generate public support for their agenda. Following the Civil War and in the midst of an unprecedented influx of immigrants, political and social reformers hoped to integrate America’s marginalized communities and to create cultural cohesion by enforcing a common spoken language, English. They sought to fashion a cohesive national plan of schooling for young citizens. Oralists crafted their rhetoric to match this mainstream ideal. Equating language with acculturation, Bell declared that, “for the preservation of our national existence,” Americans must share the same language.7 Oralists also tied speech to normality, contending that speech training would make Deaf people both less pitiable and more a part of “normal” society. In 1920, N. F. Walker argued that “[t]he deaf who make English their medium of thought are less peculiar and less suspicious than those who do not.”8

By the turn of the century, the argument for pure oral training also had the support of scientists and doctors who shared the goal of eliminating the handicap of deafness. Although medical professionals often focused more on prevention and cures for deafness, their development of hearing aids and other tests to detect and correct deafness complemented oralists’ efforts to eliminate social and educational barriers for Deaf people through oral education. Both groups sought to normalize Deaf people according to mainstream values. Enabling Deaf people to talk and, ideally, to hear better would supposedly “restore” them to the broader world. This emphasis on the physical condition as opposed to the cultural identity of Deaf people united oralists and medical specialists. Together, they built an expansive and powerful network.9

Oralists had not only the backing of mainstream society but also the financial resources to promote their agenda. Alexander Graham Bell supported oralists by contributing funds from his 1880 French Volta prize for the invention of the telephone and from his telephone patent profits. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, monetary support came also from various foundations, and organizations for the promotion of speech and lipreading blossomed. Other wealthy benefactors, such as Andrew Carnegie and Thomas Edison, took an interest in Bell’s experiments with oralism and joined the leading oral association, the American Association for the Promotion and Teaching of Speech to the Deaf (AAPTSD). By the early 1900s, the National Education Association, the oldest and largest nongovernmental educational organization, also strongly advocated oral training. Such financial and institutional support enabled oralists to initiate a massive public education campaign. Public speeches, meetings between oralists and influential politicians, and numerous articles in mainstream publications and professional journals helped to spread the concept of oralism to school boards, doctors’ offices, and state legislatures’ appropriations committees.

The majority of Deaf people consistently opposed pure oralism. They supported variations of the “combined method” instead. The flood of oralist publicity—and the spread of oralist ideology in the general society— frustrated many Deaf people.10 Public presentations of oral “successes,” deaf people who allegedly could articulate clearly and lipread with facility, particularly irritated them. Deaf advocates often condemned this oralist public relations tactic as deceptive. Most oral “successes,” they noted, were postlingually deaf, were often hard-of-hearing rather than profoundly deaf, and had intense coaching before presentations. Many could speak well before their hearing loss and could read lips more readily than the average prelingually Deaf person.

With effective oralist propaganda on its side, oralism expanded in deaf education in the first decades of the new century. Between 1870 and 1940, states and private sponsors established more than one hundred new public and private day schools for the deaf.11 Because the success of oralism depended on one-on-one work with students, schools hired many more oral teachers. They, in turn, buttressed the emerging oralist agenda. This influx of oral teachers displaced sign-based instructors in schools across the nation.

In addition, parents of deaf children supported oralism. Wanting more time with their children, parents supported oral advocates’ rally for the establishment of nonresidential schools or day schools. Parents often felt estranged from their progeny who lived in residential schools and who preferred the company of other Deaf people. Maintenance of an ongoing home life with their children and the opportunity to communicate with them in the parents’ own (spoken) language promised to help parents to minimize their children’s deafness—or the parents’ discomfort with it. Oralists’ prom...