![]()

1

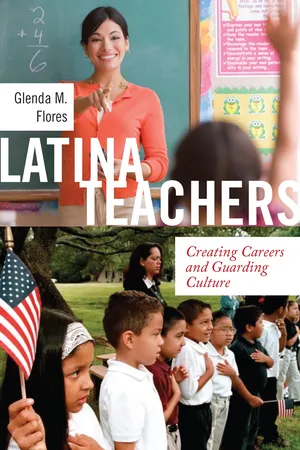

From “Americanization” to “Latinization”

“Tú vas a hablar el español” [You are going to speak Spanish], Jacqueline Arenas’s grandmother informed her when she began responding to her inquiries in English one day after school. Mrs. Arenas told me about that moment and the fear in her grandmother’s eyes to explain why she promulgated native-language retention as an ethnic cultural marker to her students in her classroom daily. She understood how her grandmother feared losing her to a schooling system that promoted English.

Her younger Latina co-workers at Goodwill Elementary1 in Rosemead, California, consider Jacqueline Arenas2 as the teacher they aspire to become. At sixty-one years old, Mrs. Arenas is among the oldest of the school’s Latina teachers, but she bursts with energy, as I observed one day in October 2009 when she hobbled hurriedly to relieve a fellow educator for yard duty during recess. While I interviewed her, she offered me Twin Dragon almond cookies that one of her Asian students had brought her. We sat by her desk in the room where she teaches a class of mostly rambunctious fourth-grade students, most of them Asian or Latino, after they had left for the day. She was wearing a purple collar shirt, blue jeans, thick black eyeglasses, long blue turquoise earrings, and white peinetas (Flamenco hair combs) on each side of her hair—a style she wore daily. I had created a sheet querying teachers about their background, and as she filled it out she talked to me about it, giving me tidbits about her background as the college-educated daughter of two U.S.-born parents who were agricultural workers. Neither of her parents graduated from high school, and they found themselves trapped in low-wage work sectors. The family’s hardships worsened when her parents divorced when she was nine and her mother had to pull Jacqueline and her siblings out of school in a barrio of La Puente, a city twenty miles east of downtown Los Angeles where Mexican immigrants predominate, to travel to different farms to pick produce to make ends meet. Mrs. Arenas recalled missing the school bus on several occasions from the fourth grade to the seventh grade in the early 1960s. She described hiding behind large trees from other school-aged children because her mother made her wear a “big old hat and long sleeves” to protect herself from the scorching sun in the fields. A Latina professional of Mexican descent,3 Mrs. Arenas had taken her grandmother’s admonishment seriously, and she still spoke Spanish confidently, with no discernible accent. While her schooling was primarily in the English language, her grandmother challenged this traditional mainstream practice by encouraging her to maintain Spanish, something that Mrs. Arenas transmitted to her students’ daily despite structural policies that forced her to do otherwise.

While in the twenty-first century it has become more common for Latino children to have a Latina teacher (Flores 2011a), scant scholarship has given voice to the challenges Latina teachers face in teaching Latino families in multiracial schools composed of different racial/ethnic minority groups. Teachers’ occupational experiences can be drastically different, influenced by the racial/ethnic dynamics of the schools, institutions, and regions in which they operate. Some, like Mrs. Arenas, have thrived. Many of her colleagues at Goodwill Elementary have as well, but the other school site where I did the research for this book, Compton Elementary, was a more difficult working environment for Latina teachers. School governance structures and colleagues and administration unfriendly to their project as cultural guardians made it a constant struggle to fight off burnout, as this book will describe. To explicate this difference, I examine the pathways into the jobs they have, how structural conditions influenced their agency and directed them to certain districts, and what creates the disparate workplace experiences I observed. The analysis will uncover some of the ways schooling and work and organizations intersect, creating differential race and cultural experiences for both Latina teachers and their families.

Mrs. Arenas’s pathway to her job had involved seventeen years at another school, and in the 1980s she was one of a few token Latina teachers. She had been at Goodwill Elementary for only four years4 and fondly remembered her previous school, which was also in the Garvey District.5 It had a strong bilingual-education6 program that catered to Spanish-speaking Latino students, but it was ultimately closed down because of low enrollment, a problem she attributed to misinformation among parents.7 An avid proponent of bilingual education, she was saddened when California’s voters eliminated it. “I don’t think people understood the merits of the program,” she said.

This book is situated at an important historical moment in California as college-educated Latinas succeed white middle-class women in the teaching profession and the presence of majority–minority schools grows throughout the state. Newly minted college-educated Latinas have been entering this feminized occupational niche in droves, especially in schools in immigrant and racial/ethnic minority communities (Ochoa 2007). While the issue of a lack of minority teachers has typically driven studies on Latina teachers, they are the fastest-growing nonwhite group entering the teaching profession (Feistritzer 2005; Flores and Hondagneu-Sotelo 2014). Women of Latino origin are more than 18 percent of teachers in California, and Latino children, who constitute 20 percent of K–12 schools nationwide, are more than 50 percent of California’s student population; thus there is a Latinization of schools and the teaching profession (California Department of Education 2015).8 These demographic shifts are especially pronounced in Los Angeles, where Latino students now make up nearly two-thirds of the K–12 population and Latinas/os constitute almost 30 percent of teachers (Ed-Data 2015).

Historically, children of Mexican origin experienced “Americanization” programs to hasten assimilation in the United States (González 1997; Ochoa 2007; Urrieta 2010). Remnants of these policies still permeate the organizational culture that Latina teachers encounter daily, but I found that schools where immigrants predominate allow for alternate scenarios. In the schools where they work, Latina teachers are creating apertures and quietly revolutionizing an educational system to bring Latina/o ethnic capital into the classroom, often through practices that challenge norms about culture’s place in the teaching profession. I define Latina/o ethnic capital as elements of Latino immigrants’ social origins and human capital such as language and behavioral codes. In doing so, they subvert normative rules regarding Latino ethnic culture in their jobs. I show that their efforts meet with varying results in two elementary schools, one predominantly Latino/Black and another predominantly Latino/Asian. Thus, I address the question as to whether Latina teachers’ experiences vary according to the racial/ethnic composition of teachers and students at the worksite.

Like the teachers in this study, who found work in the Garvey District in the San Gabriel Valley, most Latina teachers find employment in schools that serve predominantly poor immigrant and minority children and their families.9 These daughters of immigrants mostly grew up working-class and or poor; most are the first in their family to go to college. My observations suggest these experiences give them a sense of empathy with their lower-income Latino students as they try to find innovative ways to assist these students and their families at home to survive in an often confusing, even antagonistic, educational system. I find ethnic cultural transmission to be one of the most powerful modes of assistance, which Americanization makes vital to the well-being of these children. Whereas such programs were formal up until the middle of the twentieth century and openly degraded Mexican culture to encourage Mexican immigrants and others to shed their ethnic culture and assimilate into a white mainstream (González 1997; Urrieta 2010), children still experience pressure to assimilate and devalue their culture. The idea that Latino culture and foreign-language capabilities were pathological deficiencies and obstacles to schooling success, which schools openly embraced a century ago (Ochoa 2007), persists. And while overt policies encourage multicultural education practices in public schools (Washburn 1996; Delpit 2006; Nieto 2005), a paucity of research investigates how Latina teachers implement Latina/o cultural resources. My own, earlier research shows that when Latina teachers display their culture in schools where the majority of students are Latino, they meet resistance and hostility from white co-workers (Flores 2011a).10 Similarly, sociologist and educational scholar Angela Valenzuela (1999) suggests that for U.S.–Mexican youth, schools are a “subtractive process” where students of Mexican origin feel that teachers do not care about them or respect Mexican culture and migration experiences. This book outlines the ways in which Latina teachers navigate this subtractive schooling process that has manifested for Mexican children over several decades. These educators have generated a culture of teaching with the ultimate goal of supporting students’ long-term educational success. Latina educators now form a part of the middle class, and in their workplaces they see mirror images of their younger selves in their students. They use their own life histories to draw on Latina/o cultural resources and serve as agents of ethnic mobility, actively teaching their students how to navigate American race and class structures while retaining their cultural roots. I contend that Latina teachers serve as cultural guardians because they protect their students’ cultural identities and foster their students’ learning via their ethnic cultural capital, challenging the traditional Americanization approach that institutions and schools still favor. They are cultural guardians because they guard their students’ cultural identities within and beyond the school, but the institutions, standardized testing, and the schools in which they find themselves simultaneously regulate them because they do not follow the Americanization script.

Because all work organizations have “inequality regimes” (Acker 2006)—which serve to maintain class, gender, and racial hierarchies within a particular organization—it is important to take note of where these schools are located in relation to regional racial hierarchies because inequality regimes are fluid and tend to change depending on the organization, its racial/ethnic composition, and racial representation. Teachers who work in urban scho...