![]() PART I

PART I

The Root of the Problem![]()

1

The Liability Threat in Obstetrics

When I was a resident, I had a very old Chair who said something that stuck with me [and] helps me explain where we are now. … He said that he’s never done a cesarean that he regretted. He had done dozens and dozens of vaginal deliveries that he did, but never a cesarean. And I think that is where doctors are right now. … You’re unlikely to be the person who does the next section and gets surgical complications, but you could be the one regretting that vaginal delivery if the baby doesn’t come out perfect.

—Physician Jacob Chism

Doctor Chism, an obstetrician of twelve years at the time of the interview, is quite frank about his concern with being blamed for a bad vaginal birth outcome. His is not alone in this concern. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the professional association representing most obstetricians and gynecologists in the United States, has named malpractice liability a crisis for the profession and physicians’ practice of defensive medicine a consequence. In a September 11, 2009 press release announcing findings from a survey of its members about professional liability, Albert L. Strunk, ACOG Deputy Executive Vice President, stated, “The latest survey shows that the medical liability situation for ob-gyns remains a chronic crisis and continues to deprive women of all ages—especially pregnant women—of experienced ob-gyns. Women’s health care suffers as ob-gyns further decrease obstetric services, reduce gynecologic procedures, and are forced to practice defensive medicine.”1 In other words, ACOG suggests that physicians practice defensively to avoid lawsuits—this is code for performing more c-sections.

The Legal Environment of Obstetrics

As discussed earlier, the legal environment of health care has gone through rapid changes. To understand these changes, it is important to understand the role of insurance cycles. All types of insurance are known to go through cycles. “Hard cycles” are characterized by a lack of insurance policies and high prices, while “soft cycles” are characterized by a good supply of policies, a lack of demand, and low prices. Thinking specifically about the market for malpractice insurance, physicians and hospitals feel the pinch in hard markets because malpractice insurance policies are expensive and sometimes hard to find.2 Defined hard markets in the malpractice insurance industry have happened in the United States during 1975–78, 1984–87, and 2001–4.3 Maternity providers and ACOG describe these as periods of “malpractice crisis.” Notice that the hard cycles are relatively common and last for about three years. Although experts suggest that the most recent hard cycle in the malpractice insurance industry ended in 2004, it is not clear from talking with maternity providers or following statements from ACOG that they believe it has.

Obstetrics is notably one of the fields of medicine most affected by these cycles and has the added problem that malpractice claims are infrequent, large, and hard to predict, all of which contribute to uncertainty.4 For obstetrical medical malpractice claims opened or closed during the period January 1, 2009, through December 31, 2011, the most common primary allegation of the claims was neurological impairment (28.8 percent) and stillbirth or neonatal death (14.4 percent).5 The most common neurological impairment cases are for shoulder dystocia (where the baby’s shoulders unpredictably get stuck behind the woman’s pubic bone) and cerebral palsy (a disability involving the central nervous system that is largely believed to be due to something that occurs during a woman’s pregnancy). Incidents of shoulder dystocia and cerebral palsy are notably difficult to predict or prevent, and thus maternity providers feel that most negative birth outcomes involving shoulder dystocia or cerebral palsy are due to obstetrical maloccurrence, defined as “a bad or undesirable outcome that is unrelated to the quality of care provided,” rather than to obstetrical malpractice, which is defined as “a bad or undesirable outcome caused by medical negligence.”6 However, maternity providers believe that they will be held responsible for such birth outcomes regardless of whether they committed a medical error.

It can be argued that because most obstetrical lawsuits are tied to hard-to-predict events (shoulder dystocia and cerebral palsy) and may even occur before labor begins (cerebral palsy), the type of malpractice risk maternity providers face is markedly different from that in other medical specialties. Some births will have perfect outcomes, while others will involve birth defects and death regardless of the care a woman receives during labor and birth. Thus, one can see the precarious problem maternity providers face. This is not to say that malpractice in maternity care does not happen. Certainly there are documented cases of substandard care where women and babies are harmed because of the type or quality of care or lack of care they receive.7 But the malpractice risk is quite different for maternity providers compared to other medical providers, and they feel this difference.

From the obstetrician’s perspective, the risk of lawsuit is real. In a 2012 ACOG survey, 77.3 percent of responding obstetricians reported having had at least one lawsuit filed against them in their career, with an average of 2.69 lawsuits per obstetrician.8 In fact, nearly every physician in high-risk specialties, including obstetrics, will be subject to a malpractice claim by the age of sixty-five.9 While obstetricians have the third-highest rate of suit after neurologists and neurosurgeons, the average claim payment for obstetricians is almost 20 percent higher than the overall average claim payment for all specialties, and obstetricians have the highest total number of claims paid among all medical specialties.10 The average claim payment for ob-gyns in 2012 was $510,473 and differs markedly by primary allegation: $982,051 for neurological impairment; $364,794 for “other infant injury—major”; and $271,149 for stillbirth or neonatal death.11

In terms of the disposition of malpractice claims, examining claims closed between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2011, 43.9 percent were dropped by plaintiffs’ attorneys or were settled with no payment to the plaintiff, 38.7 percent were settled by a payment to the plaintiff on behalf of the obstetrician, and 17.4 percent were closed through a jury or court verdict or through arbitration.12 When the lawsuit went to trial, the court decided in favor of the obstetrician in 65.6 percent of those cases.13 Doing some quick math, what this means is that payment on behalf of the obstetrician (either through settlement or court verdict) happens in less than half (44.7 percent) of malpractice cases.

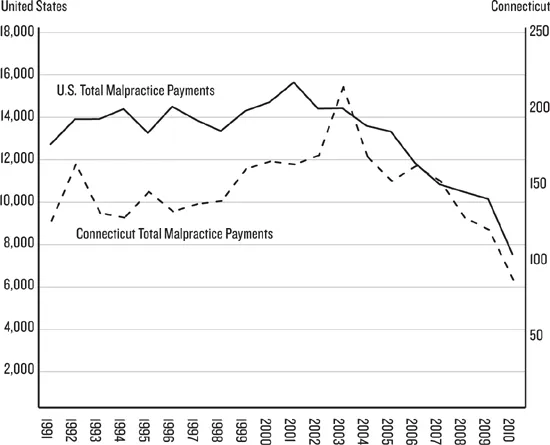

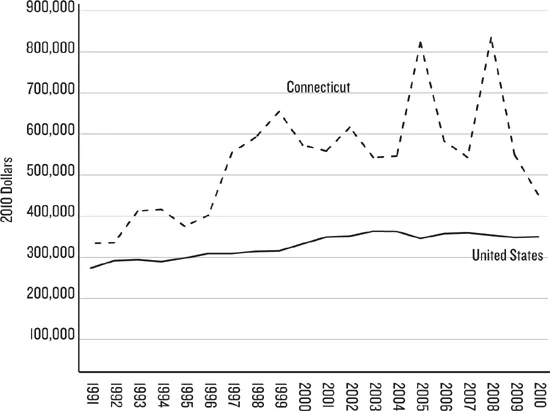

These contradictory trends—a high risk of being sued but a smaller risk that the suit will result in a payment to the plaintiff—sometimes lead critics to question the existence of a malpractice crisis.14 Other conflicting trends also lead to this doubt. For example, the number of obstetrical malpractice claims is not increasing and has actually decreased in the United States generally and in Connecticut specifically over the past twenty-five years (see figure 1.1).15 But the average payment in malpractice suits are increasing nationally and in Connecticut (see figure 1.2). In the United States malpractice claim payouts increased from an average of $254,019 in 1991 to $330,435 in 2010 (in 2010 dollars), a 30 percent increase.16 The average payment on a malpractice claim in Connecticut increased by slightly more, 38 percent, in the same period, from $314,206 in 1991 to $433,446 in 2010 (in constant 2010 dollars), although this average hides spikes in this measure, including an average of $817,092 in 2008.17

Malpractice insurance rates are also high and increasing at record rates nationally and in Connecticut. The average cost of policies offered to obstetricians by malpractice insurance companies in Connecticut increased by 92 percent from $73,451 in 1997 to $140,902 in 2012 (in constant 2012 dollars).18 Although harder to document because of regional variation, obstetrical malpractice rates have also increased nationally. For example, by one measure malpractice rates increased by 70 percent between 2000 and 2004.19

Connecticut has other characteristics that make it an interesting state to study. A 2009 report from the State of Connecticut Insurance Department concluded that Connecticut has the highest annual cost per malpractice claim.20 Further, Connecticut has had three record-breaking obstetrical malpractice awards in the past several years: in 2005 a $36.5 million cerebral palsy award; in 2008 a $38.5 million award for a neurologically impaired infant; and in 2011 a $58.6 million cerebral palsy award. The 2011 $58.6 million award replaced the 2008 $38.5 million award as the largest medical malpractice award in Connecticut history.21 Connecticut also does not have a cap on noneconomic damages, commonly referred to as a tort-cap, which is something ACOG stresses as a cure for liability crisis.

At the same time that the liability threat has been emphasized for maternity providers, changes in malpractice insurance coverage have caused them increased uncertainty. To deal with the risk of malpractice suits, maternity providers carry malpractice insurance; in fact, they are usually mandated by hospitals to purchase malpractice insurance to protect themselves in malpractice claims. There are two types of malpractice insurance: occurrence policies and claims-made policies. Occurrence policies cover all incidents that occur in the year the insurance premium is paid, regardless of when the claim is filed.22 For example, if a baby was born in 2008 and her parents file a malpractice claim in 2012, the physician’s malpractice insurance premiums paid in 2008 will cover him or her for that claim. This is in contrast to claims-made policies, which covers claims filed during the year the insurance premium is paid.23 In this same example, the physician’s 2008 premiums would cover only claims filed by a patient in 2008, meaning that if a birth occurred in 2008 and a claim of malpractice is filed in 2012, the 2012 premium would cover the claim.

Figure 1.1. Number of Malpractice Payments in the U.S. and Connecticut, 1991–2010.

Figure 1.2. Average Malpractice Payments, United States and Connecticut, 1996–2010, in 2010 Dollars.

The malpractice insurance industry has increasingly shifted to offering physicians claims-made policies. For example, in 2012, 61.6 percent of obstetricians had claims-made policies, while only 30.3 percent had occurrence coverage (8.1 percent of obstetricians were self-insured or had another unidentified type of malpractice insurance).24 Claims-made policies are advantageous to medical malpractice insurance companies because these policies decrease the length of time between policy payment and settlement.25 Insurers prefer shorter lags between policy payment and claims payment because there is less of a chance that inflation will have an effect on the size of the settlement or that a precedent-setting case will be decided that will increase the likelihood of a family winning a malpractice case.26

However, this shift in insurance coverage has had deleterious effects on physicians, “trapping” them in the profession because if they retire or stop practicing obstetrics they must still pay malpractice insurance premiums to cover any future claims that may be filed within the medical malpractice statute of limitations, which varies by state, but is on average twelve years for newborns.27 To stop obstetrical practice, physicians must pay a hefty “tail insurance” premium—typically 1.5 to 2 times the annual premium—that covers claims filed after the year the last premium was paid through the last year a patient could file a medical malpractice claim under the current statute of limitations.28 This disadvantage was noted by a number of obstetricians, one of whom, Rosemary Steel, a relatively young obstetrician in her mid-thirties, is already aware of this issue: “Most malpractice insurance carriers will give claims-made insurance coverage. … [I am] only covered for the time that [I am] around paying the bill, and then, if I want to move away, I need to pay a tail. … So, I’m kind of shackled to where I am.”

Maternity Providers’ Understanding of the Liability Environment

This feeling of being shackled because of changes in malpractice insurance policies is just the start of how aware maternity providers are of liability risk. Let me share a story to illustrate. I plan to drive across the state to interview physician Philip Burgin, but my schedule becomes too cluttered to manage the drive. I e-mail Doctor Burgin and offer to interview him by phone. I am surprised when he offers to make the three-hour round trip so that we can meet in person. Of course I agree, wondering why he is going to this trouble. We meet over coffee at a community college near my home, and it quickly becomes clear that Doctor Burgin is on a mission—to tell about the fear, anxiety, and worry he faces on a daily basis as an obstetrician. The meeting starts out as a lecture, but he softens once he figures out that I came not to indict him but rather to understand from his perspective why the c-section rate is increasing. What I learn from him is that every day he thinks about being sued and worries about not being able to put his children through college because he might lose his ability to practice. “Do you face those fears as a college professor?” he asks me.

The fear and anxiety over liability expressed by Doctor Burgin are near-ubiquitous concerns expressed by the maternity providers I interviewed. Their anxiety and fear are tied to several potential professional and economic outcomes that might result from being named in a malpractice lawsuit, outcomes from which malpractice insurance does not protect them. I have grouped these anxieties into five themes.

The first anxiety is that if a maternity provider is involved in a malpractice suit, he or she may lose malpractice insurance coverage and subsequently face escalating malpractice insurance premiums. Physician Tony Oday says, “I know somebody recently who lost her insurance because she had three lawsuits. … She’s a good physician. She just had some bad luck.” Likewise, physician Leticia Stites worries that “if you have a case and you lose, you lose your ability to practice because your rates go so high you can’t afford it.” These two fears—being dropped from coverage and facing high premiums—go hand in hand. Malpractice insurance companies do not raise the premiums of high-risk physicians; these companies rarely “experience rate” medical providers.29 What this means is that malpractice insurance companies charge the same premium to all obstetricians. Thus, rather than increasing the insurance rates of obstetricians who have malpractice claims filed against them, malpractice insurers may cancel their policies.30 In such a case the provider will have to obtain malpractice insurance from a surplus line carrier, “insurers who specialize in hard-to-insure risks,” and likely pay a much higher premium.31

A second anxiety is that a settlement or award will exceed a provider’s malpractice insurance cap, usually $1 million, and that his or her personal assets will be vulnerable. Physician Lois Timberlake articulates this fear: “I think we’ve all heard about these cases, where it’s $15 million, $20 million [awards]. … You have limits on your policy, and if the award is beyond your limits, they can go after your house, your car, your whatever, which is a very scary thought.” This concern is not without reason. A study of medical malpractice claims between 1991 and 2005 found that obstetricians were the most likely of physicians in all medical specialties to have claims closed in excess of $1 million.32

A third anxiety deals with the actual process of the lawsuit and the time and effort it takes to be involved in a malpractice proceeding. Nurse Jane Rios describes how this anxiety affects physicians:

We’ve had … physicians [who] have gone through [a lawsuit], and they’ve actually won their cases. But the time, the effort, the gray hairs that lead up to that day that you actually win the case—you age yourself ten to fifteen years just with all the stuff that you have to go through to get to it. And, yes, you win [but] … you would never want to do [it] again.

Part of the frustration mentioned by Nurse Rios is no doubt due to the length of time it takes to resolve claims of medical malpractice. Between 1999 and 2002 the average length of time from the occurrence of an alleged malpractice to the closing of the malpractice claim in obstetrics was four years, but 13 percent of claims took seven or more years from occurrence to resolution.33 Physician Philip Burgin pinpo...