![]() PART ONE

PART ONE

BEGINNINGS, 1620–1659![]()

1 / Interimperial Foundations: Early Anglo-Dutch Trade in the Caribbean and New Amsterdam

On the evening of September 29, 1632,1 the governor of the small and struggling English colony of Nevis welcomed a guest to dinner. Since the colony was blessed by abundant supplies of wood and water as well as a “fine sandy bay” that made it easy for “boats to land,” Governor Thomas Littleton was accustomed to receiving visitors from a variety of European empires. Their ships not only brought news, diplomatic intelligence, and fellowship, but also trade goods invaluable to the four-year-old colony that constantly feared the return of ravaging Spanish invaders. That evening his guest was David Pietersz. de Vries, a thirty-nine-year-old Dutch captain and trader who was on his way to the small settlement of New Netherland on the North (or Hudson) River but had stopped first in the Caribbean to load salt at the Dutch island of St. Martin. During De Vries's two-day stay, Littleton prevailed upon the Dutchman “to take aboard some captive Portuguese” whom he wanted delivered to the English Captain John Stone at De Vries's next stop, the English colony of St. Christopher.2 Upon arriving there, De Vries again met with the island's governor, Sir Thomas Warner, and delivered the prisoners—most likely enslaved Africans taken from a Portuguese vessel—to Stone. De Vries and Stone evidently had much to discuss for when the Dutch captain weighed anchor and sailed for Dutch St. Martin on September 2, Stone was on board, leaving his “barge . . . to follow him with some goods” later.3

While such friendly contact and economic exchange between a Dutch merchant and an English governor may at first seem surprising—one might expect men acting as agents of competing empires to have had a strained, if not hostile, relationship—their affiliation was far from aberrant. Collaboration between governors, captains, and merchants from a variety of European empires was a regular feature of Atlantic settlement in the seventeenth century. These relationships, based not upon imperial policies and designs for empire, but on shifting personal and familial relations of convenience and benefit, characterized a seventeenth-century Atlantic in which imperial borders were permeable. Though in the vanguards of rival empires, colonists from England and the Dutch Republic found that, in the Americas, success depended on cross-national cooperation. As De Vries discovered in 1632 and on two subsequent voyages, English settlers were particularly welcoming to Dutch merchants who brought goods and services to sustain their colonies in the 1620s and 1630s. Simultaneously, Dutch colonists living in New Netherland, De Vries's destination in 1632, found trade to neighboring English settlements to be a vital component of their colonial success. On the whole, the experiences of English and Dutch peoples in the Caribbean and North America during this early period of colonization taught colonists that survival and success at the periphery required them to rely not on a distant, and often aloof or distracted metropole, but on their own ingenuity in securing trade. These ideas of fluidity and openness created a lasting legacy that complicated the later imposition of rigorous imperial order on British colonial trade.

Explaining the warm reception De Vries received from English governors and merchants requires us first to understand how and why the Dutch trader came to be in the Caribbean. By retracing his circuitous route, we gain a sense of the larger patterns of colonial settlement and economic development that shaped the seventeenth-century Atlantic, as well as the trajectories of Atlantic empire building. Ultimately, these forces created the conditions of opportunity and demand that bound together fledging English colonists and Dutch traders.

Four months earlier, in May 1632, De Vries had begun the journey that took him to the Caribbean, guiding his vessel and its seven crew members away from the small island of Texel, the southwesternmost of the five Wadden Islands, which guard the entrance to the Dutch Republic's great internal sea, the Zuiderzee. Passing through the English Channel into the open waters of the Atlantic, De Vries plotted a complex course determined by the prevailing winds and currents, taking the vessel to the Caribbean before eventually arriving at New Netherland. As he examined his charts and pondered the journey ahead, perhaps De Vries thought of the thriving metropolis fast becoming the trading center of the Western world that he had just left behind. Of course, Amsterdam was not quite the city of golden light, abundant harvests, neatly creased linen, and domestic tranquility depicted in the work of Dutch genre painters, but nevertheless the city's bustling waterfront, rows of gabled townhouses fronting crowded canals, and comfortable temperatures stood in stark contrast to the often empty roadsteads, rough-hewn dwellings bordering muddy lanes, and extreme temperatures that typified many early-seventeenth-century European settlements in the Americas.4

In the spring of 1632, Amsterdam's roughly 115,000 inhabitants (10 percent of the country's population) were enjoying a remarkable, if discontinuous, period of growth that was not yet a half century old. During the first two decades of the seventeenth century, the residents of the United Provinces, only recently acknowledged as virtually “a sovereign, independent state” by the Twelve Years' Truce they signed with Philip III of Spain in 1609, began to establish the new Dutch Republic as Europe's trading center. Located at the midpoint of one of the key European trading axes—between the timber and grain that flowed from the Baltic to southern Europe and the Mediterranean goods that traveled back north again—the United Provinces were well placed to grow quickly. A variety of factors including the fall of Antwerp in 1585, the lifting of a Spanish embargo on Dutch ports associated with the Truce of 1609, and the disruptions that the Thirty Years' War caused in much of Europe reinforced the Provinces' geographic advantages and further encouraged the refocusing of Europe's entrepôt trade through the Low Countries. Together with advances in Dutch agriculture, these changes accelerated commerce and craft production, causing the United Provinces' economy to expand dramatically despite being interrupted by a resumption of warfare with Spain in the 1620s. At the center of the commercial explosion was a large population of merchants with the knowledge and credit needed to fuel economic expansion, and connected by commerce and family alliances in the leading cities of Amsterdam, Haarlem, Rotterdam, Middelburg, and Leiden.5

A series of financial innovations in capital markets and banking institutions subsequently allowed Dutchmen, led foremost by those in Amsterdam, to exploit new international trading opportunities. These advances enabled merchants to pool resources and to acquire loans at low interest rates of 3.5 to 4 percent (compared with 6 to 10 percent in England), which in turn kept their transaction costs low, encouraged commercial investment, and allowed them to hold goods in the vast warehouses that lined Amsterdam's canals until market conditions were perfect for their sale. Efficient capital markets, combined with low wages and technological advances in shipbuilding, made Dutch shipping competitive throughout Europe and the Americas, where Dutch traders could often offer goods from 30 to 40 percent cheaper than their rivals. Early success fueled future growth, and as Dutch merchants built commercial networks that spanned the globe, they were able to best European rivals by perfecting the acquisition and dissemination of market knowledge. Published in the prijs courantiers (price currents) that flourished in Amsterdam or passed trader to trader while they walked the paths of the Bourse, Amsterdam's exchange and the central node of the vast Dutch information network, intelligence about prices, markets, and foreign affairs augmented Dutch merchants' already advantageous positions.

Buttressing these financial advantages were Dutch innovations in industrial production (especially in those industries requiring significant capital investment), large urban communities from which to draw skilled workers, and supplies of scarce materials. Included in this group of industries were fine-cloth manufacture (much of which was centered in Leiden), dyestuff processing, sugar and whale-oil refining, and ceramic production. Specialization in these areas enhanced Dutch wealth and increased export opportunities. As Amsterdam's superior credit and insurance markets attracted more foreign investment and merchants capitalized on low prices to expand their share of Atlantic exchanges, Amsterdam was transformed into Europe's leading trading city and its most vibrant economy. Soon visitors from around Europe were descending on the city, walking beside its “Grafts, Canals, Cutts & Sluces, Moles, & Rivers” and declaring it “the most busy Concourse of Trafiquers, & people of Commerce, beyond any place or Mart in the world.” One even claimed that “1000 saile of shippes have been seen at one Tide to goe in and out” of the port. By the time De Vries boarded a barge and departed Amsterdam to meet his vessel in Texel, the city dominated the lucrative Baltic carrying trades, controlled much of the northern fisheries, and was beginning to secure a central place in colonial commerce in the East and West Indies.6

De Vries's Dutch predecessors had only recently charted the route he was to now follow: west through the English Channel, then south along the coast of Portugal, skirting the Madeira and Canary islands (one of the last chances to water and reprovision) before catching the southern trade winds that carried ships past the Cape Verde Islands that lay just off the west coast of Africa. Here shipmasters had a choice: they could turn eastward and sail for the Windward and Gold coasts of Africa, or head westward to the Caribbean. Not equipped to load gold or slaves in Africa, De Vries let the warm-water currents and western-blowing trade winds draw his vessel toward Barbados and into the Caribbean Sea.

MAP 1. The Atlantic in 1650

The first Dutch vessels to cross the Atlantic regularly were warships deployed to harass Spanish shipping during the United Provinces' protracted struggle for independence from the Hapsburgs at the end of the sixteenth century. As the Sea Beggars drove further and further into the Atlantic and toward the Americas, the information and riches they carried back to the Dutch Republic stimulated interest in the potential value of American trade. While formal Dutch activity in the Americas originated with the establishment of the Westindische Compagnie—West India Company (WIC)—in 1621, individual merchants began to send vessels directly to Brazil in 1587 as an extension of Dutch trade with Portugal. These mostly speculative voyages did not result in steady trade, but, combined with the fame of the Sea Beggars, they led several Dutch mercantile companies to establish more regular trade to Brazil after 1600. Although the Dutch were never the most important carriers of Brazilian sugars and brazilwood (a dyestuff), this early involvement with American commerce nonetheless whetted Dutch appetites for direct colonial trade. Meanwhile, Dutch merchants—many of them based in the West Frisian city of Hoorn—had also discovered salt pans on the Araya Peninsula in what is now Venezuela. Eager to sidestep periodic Spanish interference with Dutch trade in Iberia and needing an abundant supply of the preservative for the herring trade, Dutch traders soon flocked across the Atlantic. By the first decade of the seventeenth century, perhaps as many as a hundred vessels a year defied Spanish claims to the region and called at Punta de Araya to load salt. Soon Spanish authorities grew fearful of the Dutch presence, especially as Dutch merchantmen accompanying the salt fleets began to trade with Spanish colonies along the coast. Though the importance of these salt pans would fade once the Twelve Years' Truce reopened Spanish ports to the Dutch in 1609, the discovery of yet another potential benefit of Atlantic colonization helped generate further support for a West Indies trading company. When that company did receive a charter in 1621, the salt trade of Punta de Araya was included.7

The founding of the WIC launched a more intensive Dutch commitment to trade in the Americas. Charted as a joint-stock company, the WIC received a monopoly for trade and navigation in the West Indies, but its early priority was capturing Spanish silver fleets. While trading was initially only a secondary goal of the company, its conquest of Portuguese Brazil (1630) gave it direct access to numerous sugar plantations, and soon the WIC was using the colony as a base for exporting sugar, harassing Spanish silver convoys, and trading with Spanish colonies. The leadership of the WIC, the Heren XIX, intended trade from Brazil to be a company monopoly, but the company's inability to meet shipping demand and to halt private trade prompted them to license private merchants to manage the sugar trade. By the middle of the 1630s, about thirty-eight Dutch vessels a year carried Brazilian sugar to refiners in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and Middelburg.8

Coinciding with their acquisition of plantations to produce tropical commodities in the Americas, the WIC entered the gold and slave trades on the coast of Africa. By 1624, the WIC had seized Fort Nassau on the Gold Coast as well as trading stations at Gorée Island and at the estuary of the Congo River. From these outposts, company merchants mainly concentrated on the gold trade until Brazilian producers began to demand additional slaves. This demand initiated new conquests in 1637 against Portuguese slave factories on the Gold Coast, including the important Elmina Castle. Trade from these Dutch forts amounted to about seven hundred slaves a year between 1600 and 1645, a rate that would increase sixfold by the late 1660s. In time, the Dutch would expand their market beyond Brazil and their own colonies to reach those of the Spanish, French, and English. It would be this trade in human cargoes which would especially draw together the Dutch and English in the Atlantic into the eighteenth century, providing the foundation of exploitation upon which both countries built their empires. These three interdependent poles of commercial activity—in Europe, on the African coast, and in the Americas—established the framework by which the WIC could begin to profit from Atlantic commerce.9

With footholds along coastlines but little land under possession, private and WIC merchants quickly realized that the way to benefit from Atlantic trade was to carry European and tropical goods. These merchants discovered they could offer manufactured goods, slaves, shipping, and insurance at lower prices than European rivals, and soon they controlled a sizable portion of Atlantic commerce. By the late 1640s, Dutch vessels dominated the transportation of Caribbean sugars to Europe. While the Iberian countries entered an era of internal decline and the English and French struggled to find a profitable economic foothold in the Caribbean, Dutch traders were firmly in control of the economic fortunes of southern Caribbean colonies and Brazil.10

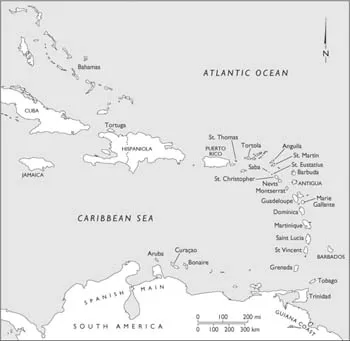

In 1632, though, these developments were only just under way as Dutch merchants like De Vries arrived in the Caribbean to investigate future possibilities for trade and settlement. After an uneventful passage in which De Vries and his crew successfully avoided the late summer and early fall hurricanes that made crossing the Atlantic that time of year so dangerous, he sighted Barbados on September 4, 1632. Two days later, De Vries and his mariners arrived safely at St. Vincent, a small island the English claimed but that was inhabited solely by one of the region's indigenous peoples, the Caribs. Pausing only briefly in the “Green Channel” off the coast, De Vries was met by Caribs in small canoes who swarmed the ship and offered “yams pine-apples, and various other West India fruits” to the sailors. After concluding business with the investigating Indians, De Vries steered for St. Martin, one of the small island colonies the WIC maintained in the West Indies, where he planned to join the eighty Dutch vessels that loaded salt from the island's salt pans each year. In the 1620s, the company had established several colonies in the Lesser Antilles including St. Martin, Saba, and St. Eustatius as well as Curaçao, Aruba, and Bonaire, just off the coast of the Spanish Main. Since these colonies were not intended to be places of permanent settlement, but rather bases from which to manage trade with a number of empires, to prey on the Spanish, to stock provisions, to maintain livestock, and to harvest salt, the Dutch settler populations in the Caribbean were small and consisted almost entirely of employees of the WIC. In the years soon after De Vries departed, these places would take on added significance as the company became more involved in the slave trade to Spanish (and eventually English) colonies. Later still, the WIC would develop two of the better-situated islands—Curaçao and St. Eustatius—into full-scale trading depots with larger, more diverse support networks.11

MAP 2. The Cari...