![]() Part I

Part I

Post 9/11, Post Modern, or Just Post Network?![]()

1

The State of Satire, the Satire of State

Jonathan Gray, Jeffrey P. Jones, and Ethan Thompson

Few would have guessed that one of the most talked about American television broadcasts of 2006, and what New York Times columnist Frank Rich would declare as the defining moment of the 2006 midterm elections, would be on C-SPAN, the congressional access channel.1 Though congressional or parliamentary access channels have cropped up around the world, offering citizens the ability to watch the political process at work and hence to serve as more knowledgeable political deliberators, such channels have tended to attract more ridicule than ardent viewers. Ironically, though, it was ridicule on offer when millions downloaded C-SPAN’s blockbuster hit of the year via YouTube and other streaming websites.

Stephen Colbert, host of Comedy Central’s The Colbert Report, had been invited to speak at the White House Correspondents Association Dinner on April 29, where he used the opportunity to launch a satiric attack on President George W. Bush and on the Washington press corps. Though many mainstream media sites hardly covered the event at first, soon the buzz that surrounded its viral spread—via emails, blogs, and conversation—forced attention. With the president meters away, Colbert’s signature satirical take on a right-wing pundit had likened the president’s few remaining supporters to the backwash at the bottom of a glass of water and, tongue firmly in cheek, praised the president for trusting his gut over facts found in books. The president’s initial laughs grew increasingly uncomfortable, as did those of Colbert’s live audience, for the satirist laid in to them, too, for being a flabby press corps that refused to question the administration. Many in the press argued that the speech was simply unfunny. But the speed and relish with which the speech circulated on the Internet attests to its popularity and resonance with a wider home audience.

This single event tells us much about the state of television satire, politics, political reporting, and television culture in the first decade of the twenty-first century. First, it speaks of the immense popularity of satire TV: being funny and smart sells and has proven a powerful draw for audiences’ attention. Second, the rapid spread of the clip highlights satire’s viral quality and cult appeal, along with the technological apparatus that now allows such satire to travel far beyond the television set almost instantaneously. Consigned to basic or pay cable channels (as it often is in the United States), satire has nevertheless frequently commanded public attention and conversation more convincingly than shows with ten times the broadcast audience. Third, since multiple commentators criticized the speech for not being funny, the speech illustrates how the presence of “humor” in political humor can rely quite heavily on one’s political world-view. It demonstrates that some satire may not even intend to be funny in a belly laugh kind of way. Fourth, Colbert’s boldness as the comedian in a room full of politicians and journalists crystallized the sad irony that contemporary satire TV often says what the press is too timid to say, proving itself a more critical interrogator of politicians at times and a more effective mouthpiece of the people’s displeasure with those in power, including the press itself. Good satire such as Colbert’s has a remarkable power to encapsulate public sentiment. Finally, then, the incident tells us of how satire can energize civic culture, engaging citizen-audiences (as few of Colbert’s press corps audience rarely can), inspiring public political discussion, and drawing citizens enthusiastically into the realm of the political with deft and dazzling ease.

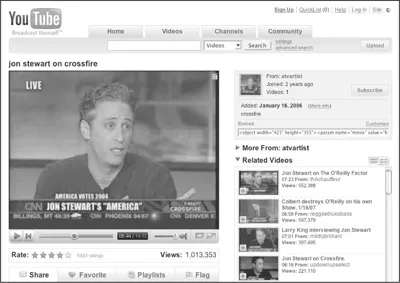

Colbert may have garnered the headlines for a time, but he has many peers. In October 2004, Jon Stewart of Comedy Central’s The Daily Show with Jon Stewart created a similar stir when he appeared as a guest on CNN’s Crossfire and lambasted the hosts for a “dog and pony show” debate format that, he charged, hurt the state of U.S. politics more than it could possibly help it (figure 1.1). In that presidential election year, Stewart was the go-to public figure for political commentary, as The Daily Show regularly featured heavily in discussions of politics. Stewart also swept up an impressive array of accolades, ranging from Entertainment Weekly’s “Entertainer of the Year” to Peabody Awards for The Daily Show’s election coverage in 2000 and 2004, and from numerous Emmys to the

Fig. 1.1. With millions of views (over 1 million views of this upload alone), Jon Stewart’s 2004 appearance on CNN’s Crossfire soon went viral, becoming one of the most talked about media events of the year.

Television Critics Association Award for “Outstanding Achievement in News and Information.” Four years later, as 2008 began with the Writers Guild of America strike still on, many worried about a presidential primary season without Stewart’s sage and witty coverage. Some people somewhat jokingly posed that The Daily Show should be declared an essential service (and therefore immune to the writer’s strike conditions for guild members).

South Park, another show on the same cable network, continued to grab headlines for its treatments of political affairs, such as the right-to-die debates surrounding the Terry Schiavo case, immortalized in the episode “Best Friends Forever.” Less scathing in nature, The Simpsons and Saturday Night Live continue to launch occasional satiric missives from their beachhead on network television. Back on cable, Aaron McGruder brought his popular comic strip The Boondocks to television in late 2005, which, along with Chappelle’s Show and The Mind of Mencia, have mixed edgy racial politics with edgy political satire. President Bush’s career was bookended by caricatures on That’s My Bush! and Lil’ Bush. Earlier, Michael Moore’s TV Nation and The Awful Truth had presented satire to audiences in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada. Indeed, satire has thrived in other nations, too. In Canada, This Hour Has 22 Minutes and Rick Mercer Report’s imprint on popular culture has been matched by few Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) shows other than Hockey Night in Canada. British television has also long featured cutting political satire, including That Was the Week That Was in the 1960s, Spitting Image in the 1980s, The Day Today and Brass Eye in the 1990s, and the more recent Have I Got News for You and Sacha Baron Cohen’s meteoric rise to international fame in the guise of his characters Ali G and Borat.

Although the collection of essays in this volume focuses on television in the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada, the unique ability of satire TV to speak truth to power (and quality demos) is apparent throughout the world. Ever mindful of expanding markets, Variety reported that comedy shows with a “satirical spin” were all the rage in China, “especially with younger, savvier urban audiences.”2 When Saddam Hussein was toppled, a new age for Iraqi television began, and one of its most successful genres was satire. The Al-Sharqiya channel was launched with political comedy as its main theme, and though its Baghdad operation was shut down by the government in early 2007, it continued to satirize war-torn Iraq via satellite transmission. A government spokesman vowed that he would love to get his hands on the producers beyond his reach: “Iraq’s anti-terrorism laws are applicable to Sharqiya because it is provoking people.”3

Television satire is flourishing in the post-network era. Indeed, with the increase in satirical programming and with the increase in the sociocultural status and prominence of such programming, it is no longer enough to refer to “satirical television,” for satire is no longer simply an occasional style (though at times it is that, too). It is its own genre, and a thriving one at that. Just as there is reality TV, self-improvement TV, teen TV, and court TV, so there is satire TV. Moreover, with many satirical shows involving politicians as guests or in caricature, with several airing on the same day and with all addressing current political issues, today’s class of satire TV forms a key part of televised political culture. Similarly, discussion of such shows informs and finds its way into all manner of discussions of local, national, and international politics. The essays in this collection seek to make sense of these programs’ role in nurturing civic culture, as well as their potential place as sources of political information acquisition, deliberation, evaluation, and popular engagement with politics.

Alongside the enthusiastic accolades for Colbert, Stewart, and company (and offsetting the shows’ fans) have been detractors who have either questioned satire’s ability to engage citizens in any meaningful way or alleged that satire may merely inspire a cynical superiority complex in viewers that removes them from politics. Writing of Stewart in the Boston Globe, for instance, Michael Kalin charged that

Stewart’s daily dose of political parody … leads to a “holier than art thou” attitude toward our national leaders. People who possess the wit, intelligence, and self-awareness of viewers of The Daily Show would never choose to enter the political fray full of “buffoons and idiots.” Content to remain perched atop their Olympian ivory towers, these bright leaders head straight for the private sector.4

Fox News’ irascible Bill O’Reilly infamously posed that Stewart’s audiences were “stoned slackers,” and even Stewart, albeit rhetorically, for years fondly clung to the mantra that his show followed a program in which puppets make prank phone calls and hence hardly positions itself as heavy politics. The Simpsons, for its part, has also been charged with being “cold,” “based less on a shared sense of humanity than on a sense of world-weary cleverer-than-thou-ness” that as a result “does not promote anything, because its humor works by putting forward positions only in order to undercut them.”5 Sometimes even compliments of contemporary satire amount to criticisms, as The Simpsons and South Park in particular are frequently noted to be willing to attack “everything,” thereby not amounting to any form of “meaningful” political discourse.

In response to such criticisms, some have pointed to the National Annenberg Election Survey or Pew Research Center figures that suggest Daily Show viewers, in particular, are a more politically knowledgeable bunch than nonwatchers.6 But attempting to rate a show’s political value by counting audiences, or even by testing their political knowledge, is both problematic (assuming, for example, that political knowledge correlates neatly to active political involvement) and insufficient. Let us as volume editors show our cards here at the outset by stating that we believe contemporary satire TV to have considerable political value, and we find many of the criticisms of satire to be weak and based on erroneous assumptions of audiences, the nature of politics, and the nature of humor, satire, parody, and entertainment more generally. As such, in this introductory chapter, we aim to define and theorize what humor, satire, and parody are, as well as their relationship to politics. We offer sections on humor, satire, and parody before turning to a cultural history of how they have evolved into their current televisual forms. We also believe that, in order to inquire into the broader questions of how contemporary television satire positions and addresses people as citizens, as well as how such shows interact with politics, close study of the programs is required. Television’s glossy surface, never-ending delivery of shows, and ephemeral nature have long seduced many into thinking that it can be criticized at speed and at a distance, but in truth it is a complex medium. Thus the authors of the chapters within this collection offer deep analyses of satirical programs in order that, together, they might provide a rich appraisal of the state of satire TV.

What Are You Laughing At? Humor as Social Critique

The initial obstacle blocking many critics of satire from seeing its political potential arises because satire is coded as a subgenre of comedy, and comedy and humor represent for many the opposite of seriousness and rational deliberation. Thus before we discuss and define satire, we find it necessary to clear a path between humor and the political. Admittedly, some simply do not want humor to have any substance, preferring to regard it as a zone of escape from real world problems that require pensive stroking of the chin, not laughter. But a closer look at humor reveals a form that is always quintessentially about that which it seems to be an escape from, and hence a form that is always already analytical, critical, and rational, albeit to varying degrees.

As Simon Critchley begins his treatise On Humour, “Jokes tear holes in our usual predictions about the empirical world. We might say that humour is produced by a disjunction between the way things are and the way they are represented in the joke, between expectation and actuality. Humour defeats our expectations by producing a novel actuality, by changing the situation in which we find ourselves.”7 This change of expectation may take various forms—from a reversal of fortunes (a rich and pompous man trips on a banana...