![]()

1

Coming of Age in a Time of War

SENSING THAT THE looming spread of World War II to the Pacific was the historic moment for which he had long waited, in early 1941, disguised as a Chinese journalist, Ho Chi Minh slipped from exile in China across the border to Vietnam, his first return to the land of his birth in thirty years. In the jungles of the rugged limestone hills near Pac Bo, Ho gathered his closest confidants and told them that the time had come to form a broad front of “patriots of all ages and all types, peasants, workers and soldiers,” to fight both the Japanese and the French, who then occupied the nation. The conspiratorial moment heralded the founding of the Viet Nam Doc Lap Dong Minh, or, more simply, the Viet Minh, and presaged more than three decades of tumult and violence; a conflagration that was at once part of a world war, a colonial war, a cold war, and a civil war.1

Born in 1937 and 1942, respectively, Pham Van Dinh and Tran Ngoc Hue were children of the storm that Ho created and came of age in an era defined by war and uncertainty. Reared in the heartland of the nation, near Vietnam’s ancient capital of Hue City, Dinh and Hue were very much alike. Children of families that boasted proud military traditions that dated back to the era of Vietnam’s imperial glory, both young men were drawn to military life and into the conflict that defined their generation. Events led both Dinh and Hue down a historical channel different from that taken by Ho and to the support of a noncommunist nationalism and a war in defense of South Vietnam. In a nation where Confucian values of family and honor are of the utmost importance, Dinh and Hue were drawn to the support of South Vietnam for the most Vietnamese of reasons, following paths blazed by their fathers.

Family Matters

Pham Van Dinh was born in Phu Cam Village, in Thua Thien Province, near Hue City, in central Vietnam, on 2 February 1937.2 Dinh’s father, Pham Van Vinh, and his mother, Cong Ton Nu Thi Nhan, were Catholics, a religion whose adherents were normally bitterly opposed to the communists. In a nation where reverence for one’s ancestors and ties to the land are paramount, when the nation was split by the Geneva Accords, in 1954, tens of thousands of Catholics, in an extraordinary move, fled their homeland in the north to be free of communist rule. These Catholics and their southern brethren formed the core of support for South Vietnam and for an alternative to a communist form of nationalism.

In Vietnam, the traditional customs of on (a high moral debt) and hieu (filial piety) undergird social reality and enshrine the family as the central unit of life. The historian Robert Brigham explains:

The idea of on was instilled in Vietnamese at a young age. Children were taught that they owed their parents a moral debt of immense proportions. The debt could never be fully repaid, but children were expected to try to please their parents constantly and to obey them faithfully. A child’s greatest comfort would come from the knowledge that he had reduced the burden of work on his parents. The debt did not diminish with age. As parents grew older, responsibility for their care rested more heavily on the children’s shoulders. A person who chose to dismiss the moral debt and live according to his or her own aspirations and desires was ostracized in a society where social standing within the family determined everything, even what a person called him- or herself and others. Repaying the debt also extended to the ancestors and the generations to come. To show gratitude for the accumulated merit and social standing that his or her ancestors had provided, each person owed the next generation his or her best effort not to diminish the family’s position within the xa (village).3

Vinh’s family had close kinship links that predisposed them to the support of the South Vietnamese state and noncommunist Vietnamese nationalism. Vinh was a cousin of Ngo Dinh Diem, the first president of South Vietnam. Nhan was a distant relative of Vietnam’s last emperor under the French and the first South Vietnamese head of state, Bao Dai, and as such was a member of the royal family. The complex web of relationships virtually ensured that Pham Van Dinh would be a loyal supporter of South Vietnam. Though the ties of kinship existed, they did not gain the family much in the way of preferential treatment. Vinh was a musician and eventually became a warrant officer in the French-supported Vietnamese National Army (VNA) of Bao Dai; he even spent a year living in France. Later, he rose to command the band of the 1st Division of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). Vinh was a warrant officer at the outset of the presidency of Ngo Dinh Diem and remained a warrant officer at the time of Diem’s assassination.

Vinh’s family was staunchly middle class and urban in a nation of peasants, further inclining it to support the Diem regime. Class ties also marked the Vinh family, and those like it, for importance and influence under Diem’s rule; the officer class of the ARVN, like the merchant class, was overwhelmingly middle class and urban. The education level and loyalty of the class as a whole made for good officer material. However, the class was demographically narrow and arguably separated from the wants, needs, and desires of the vast majority of the Vietnamese citizenry.

Pham Van Dinh thus came by his support for South Vietnam quite naturally as a member of a southern, Catholic, middle-class, urban family. He was, indeed, exactly what outsiders would expect to find when researching the background of a South Vietnamese officer. Even in the case of his family, though, things were not simple in the chaos that was post–World War II Vietnam. In 1945, Vinh’s elder brother had opted to join and fight with the Viet Minh against French colonialism, and he remained a supporter of the Viet Minh until his death shortly after the communist victory at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. The conflict in Vietnam was much more complex than most American histories of the war allow. It was, in many ways, a true civil war, pitting brother against brother and splitting families—even families in which all ties seemingly led to support of South Vietnam, as in the family of Pham Van Dinh.

Tran Ngoc Hue was born in Hue City on 4 January 1942. The Tran family had long followed the Nguyen emperors of Vietnam and had moved south with the tide of Vietnamese expansion hundreds of years prior to Hue’s birth. The family had a storied military tradition in service of the Vietnamese state. Raised on stories of his family’s martial bravery, Hue longed to emulate his heroic ancestors, including his great-great-grandfather General Nguyen Tri Phuong, a fabled Vietnamese hero who fought valiantly against encroaching colonialism and who committed suicide in 1873 when Hanoi finally fell to French rule. With regard to family military prowess of a more recent vintage, Tran Ngoc Hue’s uncle, Tran Huu Dieu, was a prominent military officer in the Bao Dai regime before 1945, while several of Hue’s cousins served in the VNA and later the ARVN. Most importantly, though, Hue’s father, Tran Huu Chuong, remained true to the family tradition and served as a junior officer in the VNA. As momentous events ripped Vietnam apart, Chuong stood against colonialism and against communism. Rejecting both the Viet Minh and the French, Chuong sought another path toward true independence for his home-land, a noncommunist form of Vietnamese nationalism, and eventually swore loyalty to the new nation of South Vietnam. Chuong hoped for the reunification of his country, but under noncommunist rule—a hope that soon became the motivating force in the life of young Tran Ngoc Hue.

Hue’s mother, Nguyen Thi Nghia, was Catholic, whereas his father, Chuong, was a Buddhist. Though Nghia held true to her own religion, the Tran children were raised Buddhist, the religion of the vast majority of the Vietnamese people. While many Buddhists feared dominance by an avowedly atheist communist regime, the Buddhist community in general did not feel the same level of persecution and resulting anticommunist unity that characterized the Catholic minority in Vietnam. In the case of the Trans, adherence to Buddhism meshed well with support for noncommunist nationalism. However, the situation, especially within the upper echelon of the Buddhist power structure, was exceedingly complex.

Buddhism in Vietnam lacked coherent organization, with most Vietnamese Buddhists practicing an eclectic mix of Asian religions under the loose organization of the Buddhist faith. Even at the very highest levels, Buddhism in Vietnam was fragmented, pulled in different directions by different sects and different charismatic leaders. In general, much of the Buddhist leadership not only stood against communist rule but also sometimes railed against the dictatorial tendencies of Ngo Dinh Diem, with often bloody results. Some of the more politically able Buddhist leaders even saw their movement as a logical middle ground between the extremes represented by Ho Chi Minh and Ngo Dinh Diem. To some, then, Buddhism represented a neutralist hope to end the war while still attaining the goals of Vietnamese nationalism, while, to others, those who passed as neutralist Buddhist leaders were little more than communist stooges.4

Though his family was not rich (his home did not even have electricity until 1952), Pham Van Dinh’s parents toiled and sacrificed to put their nine children through private Catholic schools. The young Dinh appreciated and honored the hard work put in by his father, but his mother was the primary influence on his life. Throughout his life, Dinh was quite conscious of the fact that his mother reveled in his success, a fact that urged him ever onward to provide her with further honor and prestige.

At the age of eight, Dinh enrolled in the prestigious Pellerin School in Hue City. The staff of the Catholic school was made up, in the main, of priests and other religiously affiliated teachers who often taught classes in French and followed a French classical educational pattern. Dinh remained in the school for some thirteen years, a rarity in a country where few could afford even a short period of expensive private education. Though Dinh was much less well off than many of his classmates, he realized even then that his access to such a good education placed him in the upper stratum of Vietnamese society.5

It was a heady time to be a young schoolboy, as great events shook the very foundations of modern Vietnam. While he was in school, the Viet Minh came to power, the French returned and were eventually defeated, the Geneva Accords split Vietnam, and South Vietnam rose in opposition to the communist state of North Vietnam. All the while, Dinh watched the events from the safety of his school, as his elders made the critical decisions of their lives. Dinh’s teachers were Vietnamese Catholics and as such mainly stood against both French colonialism and communism. However, a few of his teachers were old-style proponents of French rule, while others were avowed supporters of the Viet Minh.

Though he was aware of the cases in favor of both French and communist rule over Vietnam, Dinh was more influenced by his family background and natural predilections, which led him to adopt the majority viewpoint of the teachers and students at Pellerin School. Accordingly, Dinh developed a personal level of support for noncommunist nationalism in Vietnam and eventually supported the Ngo Dinh Diem regime. In his case, it was a natural occurrence that had to happen and required little thought.

In the elite school, the teachers pushed their pupils to excel; reaching heights of excellence was their duty to their family. It was also their duty to the state. The faculty, whether Viet Minh, Francophile, or southern nationalist, also taught the students that they were the natural leaders of Vietnamese society. They would be the military commanders, political leaders, and business magnates of the future, charged with lifting Vietnam from its present period of chaos and discord.

As his time in school neared its end, Dinh, who had always excelled in his studies, knew his place in society. Though there were many avenues of advancement open to him, Dinh chose to seek a career in the military. He could have just done his required national service and spent much of the coming war behind a desk. However, Dinh was driven—for himself, his family, and his nation. Thus, he chose to enter the Thu Duc Reserve Officers School outside Saigon and to pursue a career as a combat officer in the infantry. Again, it just seemed the natural and proper thing to do. As he set out on his military journey, it was with high expectations. He did not hope or dream; he knew that he would become a general.

The family of Tran Ngoc Hue remained in Hue City until the chaotic period at the close of World War II. The occupation of the city by Japanese troops, and the subsequent turmoil in the nation, forced the Trans to flee to their ancestral village of Ke Mon, twenty kilometers to the northeast. Most of Hue’s family remained in Ke Mon, a Viet Minh–dominated area, for the next decade. Chuong, however, rejoined his unit in the VNA and took part in the fighting against the Viet Minh. The situation was difficult for young Hue, living in “enemy” territory and under constant scrutiny while his father was away fighting in the unending conflict.

During this stage of the war, two events provided Tran Ngoc Hue with very powerful motivation for his future career in the South Vietnamese military. Ke Mon was something of a battleground area and suffered at the hands of both sides in the conflict. In 1950, while only eight years old, Hue witnessed a Viet Minh ambush of a Vietnamese government patrol—soldiers like his father. After a brief firefight, the government soldiers realized that they were outnumbered and out-gunned and chose to surrender. The Viet Minh fighters stripped the prisoners in an act of ritual humiliation and tied their hands behind their backs. Hue then watched in horror as the Viet Minh buried the government soldiers alive, not wanting even to waste bullets to kill them. It was an act of barbarity that Hue never forgot.

Such an act could not go unpunished, and French forces soon arrived in Ke Mon to administer justice. As was often the case, the Viet Minh had fled, but it made no difference. An example had to be made. Much of the local population was rounded up and herded into a few buildings, while French soldiers put several homes in the village to the torch. Hue’s house was not burned, but the soldiers burst into the building and gathered the family into a single room. Then two French soldiers forced one of Hue’s young cousins away and took turns raping her. Thus, Hue came to hate the French occupiers as well as the Viet Minh. Neither the communists nor the French had brought anything but death and destruction to Ke Mon. Both were evil and had to be fought. Only support for the Vietnamese government forces, represented by his father, seemed to be justified. Both Dinh and Hue came to their support of South Vietnam naturally, but Tran Ngoc Hue was also driven by the strong and less mutable force of revenge when he dedicated his life to noncommunist Vietnamese nationalism and fought for the nation that became South Vietnam.

Soon Hue went off to a unique boarding school far to the south in Vung Tau. Based on a French model, the Truong Thieu Sinh Quan was a school dedicated to the education of the sons of ARVN officers and men, a school meant to mold the military leaders of the future. Hue received not only a general education based on the French classical model but also a military tutelage served with heavy doses of South Vietnamese patriotism. Hue learned that he was a natural leader of his people and that the ARVN was the vehicle through which Vietnam would achieve peace and reunification. Most importantly, though, Hue learned much regarding his sacred duty. He and his future cadre of South Vietnamese leaders were “responsible for the peace and prosperity of his people.” Very much like Dinh, Hue learned his place in society in school, while also learning of his duty to lead his people in war. Adding his new lessons to his hatred of the communists, he found that his next move was natural. Hue enrolled in the prestigious Vietnamese National Military Academy at Da Lat. Hue’s mother was initially disturbed by his decision and feared for her son’s life. However, she too had been affected by what she knew of the Viet Minh and put patriotism before family and urged her son forward with his decision. With his drive and his grim determination, coupled with his prodigious academic skills, Tran Ngoc Hue did not hope or dream—he, too, knew that he would become a general.

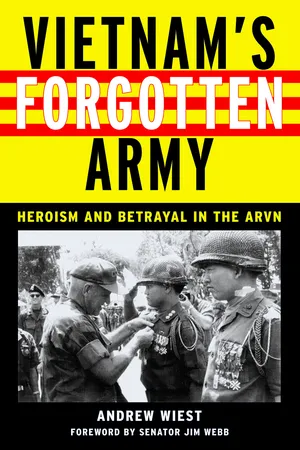

Tran Ngoc Hue (second from the left) as a thirteen-year-old student at Truong Thieu Sinh Quan school for the children of ARVN officers and men. Photograph courtesy of Tran Ngoc Hue.

The popular Western perception is that Ho Chi Minh and his followers were the only inheritors of the mantle of Vietnamese nationalism. As a result, it is common belief that very few, for quite special and narrow reasons, chose to follow the corrupt and dictatorial regime of South Vietnam, which was, after all, only an American creation. It follows, in this version, that the leaders of the South Vietnamese regime, and its military, were in the main Catholics who had a religious score to settle with the communists or were grasping urbanites who sought only to gain economically from their association with the regime. These few men were not leaders in the true sense of the term. They were self-serving and greedy, not heroic. They led the ARVN badly and gave the soldiers themselves little more than a meaningless death.

Pham Van Dinh and Tran Ngoc Hue were and are clearly exceptional. They were the best of the best—and became the bright young stars of the ARVN. However, just a cursory glance at their background and upbringing reveals that the situation in Vietnam and in the ARVN was much more complicated than most Westerners c...