![]()

Part I

Contexts of Development

An Ecological Framework

Carola Suárez-Orozco, Mona M. Abo-Zena, and Amy K. Marks

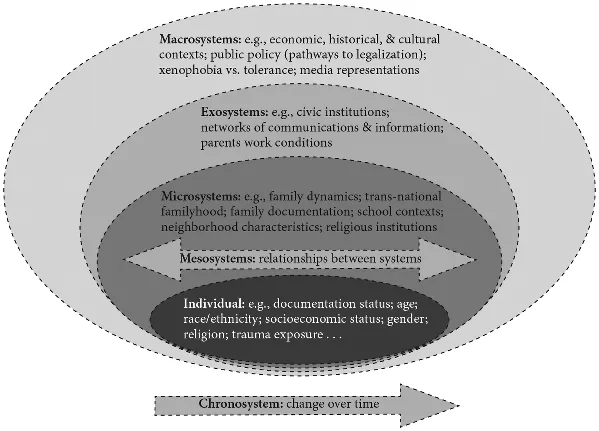

In this first set of contributions to the book, we consider several broad social contexts to set the stage for understanding the development of immigrant-origin children and youth. These contexts, derived from an ecological model of human development introduced by Urie Bronfenbrenner1 are those that matter in unique ways to inform the overall functioning of immigrant families and the development of their children.

Like all children, immigrant children’s experiences are a result of reciprocal interactions between their experience and their environment. Outcomes will vary as a function of the child, their culture, and their environment over the course of time. Each child has their own set of characteristics that when interacting with the environment will place them in varying positions of vulnerability or strength. Put simply, all children grow within cultural contexts that shape their future selves. By studying immigrant child development in new—and oftentimes competing—cultural environments, we learn more deeply about the ways all children make adaptations when faced with novel cultural contexts. For immigrant children, some critical individual characteristics shaping development are the child’s age at migration, race and ethnicity, language skills, exposure to trauma, sexual orientation, and temperament. Microsystems are the settings and arrangements with which the child comes into direct contact, such as family, peers, community, and religious organizations. Mesosystems are the interconnections among the various microsystems (such as the relationship the parents have with school personnel); these have an indirect but nonetheless important effect on the child. Exosystems, another sphere of indirect effects, are the interconnections among settings and larger social structures that influence the child (such as the safety of a mother’s work environment, which can in turn influence her mental health and her consequent psychological availability to her child). The macrosystems are the larger political, economic, or social forces that nonetheless have a distinct influence on the child’s life (such as a political coups or the Great Recession). The chronosystem represents developmental changes over time. (See figure I.1, a depiction of the ecological model of immigration with a focus on adaptation to the new land.)

The chapters of this section consider some of the critical contexts of development that immigrant-origin children and youth navigate in ways that are distinct to their experiences. It is beyond the scope of this book to address all dimensions of the model that influence the immigrant child and youth experience. In this section, we feature dimensions that are particularly important and unique to their development. Transnational familyhood constitutes an ecological context specific to immigrant-origin children and youth that is both physical and emotional in nature, with varied effects on family functioning.2 In two chapters of this section, we consider both family reunifications following separations during the initial migration of the parents and the process of maintaining communication with loved ones across transnational borders. Schools are the setting in which the immigrant child must first systematically cross the boundaries between the home culture and the host culture on a daily basis. Globally, religion plays an important role in the majority of people’s lives; it does so in many immigrant families’ lives, particularly since religious institutions provide a vital context as immigrants navigate the unfamiliar landscapes of a new homeland.3 Lastly, national immigration policies provide a context of development that is unique to contemporary immigrant-origin children and youth.

In the study of transnational familyhood in chapter 1, Carola Suárez-Orozco describes how global migrations transform the shape and definition of a family. What does it mean to be a parent, a child, or even a “family unit” in the transnational circumstances of global migration? This chapter explores varieties of family relations, such as the biological parent who sends funds from the United States to support their children and the grandparent, aunt, or uncle in the home country who provides for the children’s daily needs. Is the children’s attachment to the “functional everyday parent” different from that to the long-distance parent? This chapter draws from both qualitative and quantitative studies to illustrate both the joyful and the stressful reverberations of the reunification process for children and their families.

Connecting home and school settings, in chapter 2, Amy K. Marks and Kerrie Pieloch focus on the school contexts of immigrant youth in the United States. Regardless of cultural background, family economics, or documentation status, most immigrant-origin children and adolescents attend schools in the new land. This chapter explores the unique aspects of immigrant-origin children’s preschool, primary school, and secondary school contexts, including school resources and language programs, student-teacher body characteristics, and issues related to differences between the family and school cultures. In addition, the chapter explores characteristics and challenges of school-level immigrant peer networks, such as segregation and discrimination, that immigrant children and youth encounter in the school climate.

While forging new connections at school, immigrant-origin youth also develop and maintain their heritage-country connections. Examining another unique manner in which family contexts are shaped by migration, in chapter 3, Gonzalo Bacigalupe and Kimberly Parker discuss the many ways in which immigrant-origin youth connect to the culture of their heritage country and with family members living there. The authors pay particular attention to the increasing use of digital technologies that both shape and maintain the quality of these connections. Historically, the parent generation tended to manage contact with families in the heritage country. However, within the time span of a generation, the handwritten letter that once took months to arrive and the costly long-distance telephone call have become obsolete. With changes in the availability and affordability of technology that now enable rapid and instant communication, Generation M members can now develop and maintain their own qualitatively different relationships with the heritage country and its residents. By analyzing the contexts created by satellite dishes, the Internet, and smartphones, this chapter shows how Generation M has been able to stay connected with others, resulting in altogether different social, cultural, economic, and political exchanges from those available to previous immigrant generations. This chapter also describes how such connections may affect family functioning and contribute to socioemotional development.

While religion and religious contexts play a prominent role in human development generally, in chapter 4, Mona M. Abo-Zena and Meenal Rana describe the multiple ways in which religion may be particularly salient for immigrant-origin families. Religious communities and faiths generally provide them with spiritual guidance and fellowship as well as material support. For immigrants, religious contexts are often coethnic and offer a space for religious, cultural, and ethnic socialization of children. Although a source of support, religion and religious contexts may also challenge the development of immigrant children and youth in various ways such as precipitating a crisis in faith, highlighting differences in degrees of religious commitment between an individual and their family or community, and contending with religious-based discrimination or alienation. The authors also provide examples of how religious content and immigrant context may interact, producing variations in practices that have implications for practitioners and researchers.

At the furthest levels of the ecological model, laws and macro-level contextual processes within a society can have a profound influence on the daily lives and functioning of immigrant-origin children and youth. In chapter 5, Carola Suárez-Orozco and Hirokazu Yoshikawa describe a context that is emotional rather than physical—the very palpable experiences that derive from living in a family with members who have various undocumented legal statuses. An estimated 5.5 million children and adolescents are growing up with unauthorized parents and are experiencing multiple and often unrecognized developmental consequences resulting from their family’s existence in the shadow of the law. Although these youth are American in spirit and voice (and three-quarters are citizens themselves), they are nevertheless members of families that are considered “illegal” in the eyes of the law. The authors elucidate the various dimensions of documentation status—going beyond the binary of the “authorized” and “unauthorized.” They show how undocumented status cuts across every sector of the ecological framework, influencing multiple developmental outcomes with implications for immigrant children’s well-being as well as for the nation’s future.

Notes

1. Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R. M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1, Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 793–828). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

2. Suárez-Orozco, C., & Suárez-Orozco, M. (2013). Transnationalism of the heart: Familyhood across borders. In D. Cere & L. McClain (Eds.), What is parenthood? (pp. 279–298). New York...