![]()

1

Two Tales of Stop and Frisk

[T]here must be a narrowly drawn authority to permit a reasonable search for weapons for the protection of the police officer, where he has reason to believe that he is dealing with an armed and dangerous individual, regardless of whether he has probable cause to arrest the individual for a crime. The officer need not be absolutely certain that the individual is armed; the issue is whether a reasonably prudent man, in the circumstances, would be warranted in the belief that his safety or that of others was in danger.

—Chief Justice Earl Warren, Terry v. Ohio, 19681

In conclusion, I find that the City is liable for violating plaintiffs’ Fourth and Fourteenth Amendment rights. The City acted with deliberate indifference toward the NYPD’s practice of making unconstitutional stops and conducting unconstitutional frisks. Even if the City had not been deliberately indifferent, the NYPD’s unconstitutional practices were sufficiently widespread as to have the force of law.

—Judge Shira Scheindlin, Floyd v. City of New York, 20132

The two quotes above represent fifty-year bookends to the stop and frisk—or Terry stop—story.3 The first quote is from the U.S. Supreme Court majority opinion in the Terry v. Ohio case, written by Chief Justice Earl Warren. The facts of the Terry case highlight the core principles of stop, question, and frisk (SQF). In October 1963, a Cleveland detective witnessed two men standing near a jewelry store. The detective observed the suspects as they continued to move up and down the street and look into the windows of the jewelry store. When they were joined by a third man, the detective suspected that they were either about to rob the store or were casing it for a later robbery. The detective approached the suspects, identified himself as a police officer, and because he thought that they might be armed, he conducted a “pat-down” search over the clothes of the suspects. Two of the three men were armed with revolvers and were subsequently arrested and prosecuted for carrying concealed weapons. Both were convicted and appealed their case to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1968 the Court upheld the convictions and acknowledged the constitutionality of “stop and frisk” searches—as indicated by the quote from Chief Justice Warren. Though the basic principles underlying SQF can actually be traced back to English common law, the Court’s ruling in the Terry case formalized the authority of the police to stop citizens on the street based on a standard of proof lesser than probable cause, and it also gave them the right to conduct superficial “pat-down” searches of those citizens whom they stop (under certain conditions).

The second quote is from the federal district court ruling in the case of Floyd v. City of New York (2013).4 This ruling was the culmination of more than a decade of litigation against the New York Police Department (NYPD) for its use of SQF. The genesis of the NYPD’s reliance on SQF can be traced back to the dramatic increases in crime, violence, and disorder that occurred during the late 1980s, much of it associated with the drug trade.5 The explosion of violence during the late 1980s and early 1990s is evidenced by the number of homicides in New York, which jumped from 1,392 in 1985 to 2,262 in 1990 and remained above 2,000 through 1992. The level of social and physical disorder that emerged in conjunction with the violence was similarly destructive.6

In 1994 William Bratton was hired as the police commissioner of the NYPD. Bratton had just achieved considerable success cleaning up the New York City subway system as the Transit Police chief, and he was hired by Mayor Rudolph Giuliani to bring that success to the streets of New York. Bratton revamped and restructured the NYPD in a number of ways, including a focus on both disorder and low-level crime as well as illegal gun carrying. SQF became the primary tactic employed by all NYPD officers to combat disorder, low-level crime, and illegal gun possession. Indeed, seizure of illegal firearms through SQF became a major performance indicator for officers. Physician Garen Wintemute noted that in just three years, the NYPD made over 40,000 gun arrests and confiscated more than 50,000 guns.7 Bratton’s philosophical, structural, and operational changes to the NYPD coincided with historic drops in crime, perhaps best illustrated by homicides, which fell precipitously through the rest of the decade and into the twenty-first century. From 2003 through 2009, the city averaged 540 homicides annually, down from more than 2,000 in 1992. The causes of the New York City crime decline, and the role of the NYPD (and SQF) in that decline, have been hotly contested.8

The Controversy

Over the next two decades, the NYPD’s use of stop and frisk continued to increase, peaking at over 685,000 stops in 2011. During this time, however, serious questions had begun to emerge in New York regarding the practice, especially with regard to the disproportionate impact on minority citizens. In 1999 the Office of the New York State Attorney General released a report that examined 175,000 stops and raised serious questions about their constitutionality (15 percent did not meet the reasonable suspicion threshold), as well as racial disparities in those who were subjected to SQF.9 Criminologist Jeffrey Fagan and colleagues noted that “by the end of the decade, stops and frisks of persons suspected of crimes had become a flashpoint for grievances by the City’s minority communities.”10 Allegations of racial discrimination in stops conducted by the NYPD led to two lawsuits. The first, Daniels v. City of New York,11 was filed in 1999 by the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) and settled in 2003. As part of the settlement, the NYPD agreed to maintain a written anti–racial profiling policy; to audit officers’ stops to ensure their adherence to both department policy and the law; and to provide the results of those audits (as well as data on all stops) to the CCR on a quarterly basis.12 Despite this settlement, the CCR filed a second suit in 2008, Floyd v. City of New York,13 alleging that the NYPD had violated the earlier settlement and was continuing to “engage in racial profiling and suspicion-less stops of law-abiding New York City residents.”14 The controversy came to a head in August 2013, when Judge Shira Scheindlin of the federal district court in Manhattan ruled that the NYPD’s stop and frisk program was unconstitutional; the second quote at the start of this chapter is from the judge’s ruling in the Floyd case.

The ruling in Floyd demonstrated how the use of stop and frisk as a widespread crime-control strategy could go terribly wrong, leading to the violation of the constitutional rights of thousands of mostly minority New York City residents for a period of nearly twenty years. Importantly, Judge Scheindlin’s ruling in Floyd was one of several cases pending before her at the time that involved NYPD’s SQF practices. Ligon v. City of New York15 involved stops outside private residences, and Davis v. City of New York16 involved stops in public housing. All three cases alleged Fourth and Fourteenth Amendment violations.

A number of studies have documented the disproportionate focus of stop and frisk on minority citizens in New York’s low-income, high-crime neighborhoods, as well as the severe and varied impact caused by those stops. For example, the Vera Institute of Justice surveyed more than five hundred young, mostly minority New Yorkers (aged thirteen to twenty-five) and found that 44 percent reported being stopped by the NYPD nine or more times; nearly half reported that the officer threatened or used physical force during the stop.17 The Center for Constitutional Rights interviewed fifty-four individuals who had been stopped by police and concluded,

These interviews provide evidence of how deeply this practice impacts individuals and they document the widespread civil and human rights abuses, including illegal profiling, improper arrests, inappropriate touching, sexual harassment, humiliation and violence at the hands of police officers. The effects of these abuses can be devastating and often leave behind emotional, psychological, social and economic harm.18

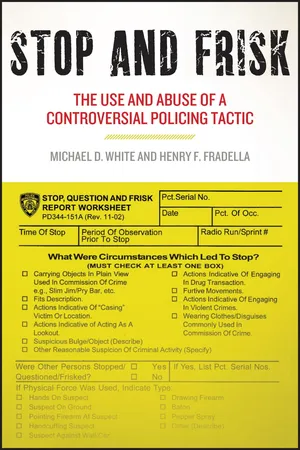

Scholars have also demonstrated the low return on the hundreds of thousands of Terry stops. Criminologist Delores Jones-Brown and colleagues found that, of the 540,320 stops in 2008, just 6 percent resulted in an arrest (and an additional 6.4 percent resulted in a summons).19 Jones-Brown and colleagues also noted that, as the percentage of “innocent stops”—those not resulting in summons or arrest—has consistently remained between 86 and 90 percent, the percentage of stops resulting in the recovery of a gun has dropped by 60 percent (from 0.39 percent in 2003 to 0.15 percent in 2008).20 These findings are especially troubling given that there are indications that large numbers of stops occurred without formal documentation (e.g., one police commander estimated that only one in ten stops was documented by officers on the department’s formal SQF form, the UF-250).21

Though the SQF issue is often viewed as solely a New York problem, the strategy has generated similar controversies in other jurisdictions throughout the United States. The Philadelphia Police Department stopped more than 250,000 citizens in 2009, and in November 2010 the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Pennsylvania filed a lawsuit in federal court alleging that the Philadelphia Police Department was engaged in widespread racial profiling. In June 2011 the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania approved a settlement agreement (i.e., consent decree) between the plaintiffs and the Philadelphia Police Department, which included quarterly analysis of stop data by the ACLU, appointment of an independent monitor, retraining of officers, and new protocols governing SQF practices.22 A report by the ACLU of New Jersey examined SQF activities of the Newark Police Department during the last half of 2013 and concluded, “Newark police officers use stop-and-frisk with troubling frequency; Black Newarkers bear the disproportionate brunt of stop-and-frisks; [and] the majority of people stopped [75 percent] are innocent.”23 An investigation into SQF activity by the Miami Gardens Police Department found that, from 2008 to 2013, officers had stopped 65,328 individuals, and nearly 1,000 citizens had been stopped ten or more times. Moreover, only 13 percent of those stopped were arrested.24 Similar controversies have arisen in Baltimore, Chicago, and Detroit.25 Clearly, police overuse and misuse of stop and frisk is not just a New York problem. It can occur anywhere.

The Disconnect between Principle and Practice

The discussion over the last several pages highlights the disconnect between stop and frisk in principle and in practice. On the one hand, Terry stops are constitutionally permissible and are grounded in a historical and legal tradition dating back hundreds of years. The basis of a police officer’s authority to stop and question a suspicious person can be traced back to English common law, and has been affirmed by a host of court cases and federal law both before and after the ruling in Terry v. Ohio in 1968. For example, under English common law, watchmen and private citizens had the authority to “arrest any suspicious night-walker, and detain him till he give a good account of himself.”26 In 1939 in the United States, the Interstate Commission on Crime drafted the Uniform Arrest Act, which outlined nine different types of police-citizen contact, including “questioning and detaining suspects” and “searching suspects for weapons.”27 The SQF practice was, of course, formally established in the 1968 ruling in Terry v. Ohio, but since then, the Court has both consistently reaffirmed the constitutionality of SQF and expanded officers’ authority during such stops.28 For example, in Alabama v. White (1990), the Court extended police officers’ authority to conduct vehicle stops based on anonymous tips alleging criminal activity.29 In Whren v. United States (1996), the Court held that pretextual stops were constitutional, allowing officers to stop citizens for minor violations in order to investigate for other, more serious criminal activity.30 Last, police leaders have consistently asserted that SQF is a critically important tool for police to effectively combat crime. In 2014 (after the federal court ruling in the Floyd case), Police Commissioner William Bratton said of SQF, “you cannot police without it.”31

On the other hand, the events in New York, Philadelphia, Miami Gardens, and other jurisdictions tell a very different story. It is a tale of gross overuse and misuse of the strategy, violations of citizens’ Fourth and Fourteenth Amendment rights, strained police-community relationships, low or no police legitimacy, and significant emotional, psychological, and physical consequences experienced by citizens. This is also a story of abused police discretion. The decision by a police officer to initiate a Terry stop is an exercise in discretion. There is a long history of police problems with discretion, ranging from use of deadly force and automobile pursuits to arrest decisions in domestic violence calls. The stories from New York and elsewhere illustrate that unjust, unconstitutional stop and frisk represents another in a long line of failures by police departments to properly guide and control their officers’ use of discretion.

As a consequence, the term “stop and frisk” has in many places become synonymous with racial profiling. The line between a sound, constitutionally approved police practice and racial profiling has become so blurred that some city and police leaders have faced media scrutiny and backlash from citizens when they consider adopting a stop and frisk program.32 Recent events in Detroit illustrate the now intimate connection between racial profiling and the practice. In late 2013 the Detroit Police Department partnered with the Manhattan Institute to develop an SQF program in Detroit. The announcement of the program drew significant criticism from local civil rights advocates and local media. Referring to the Floyd ruling in New York, an op-ed by the editor of a local newspaper concluded, “Because of this recent ruling and long-documented history of racial tension within the city, bringing the program to Detroit would likely create a complicated judicial process before results could even be seen on the streets, ultimately doing more harm than good.”33

The central focus of this book is the disconnect between current perceptions of SQF as a form of racial discriminati...