![]()

1

Technology Myths and Histories

In June 2011, I found an interesting T-shirt in Tahrir Square, the central public space in Cairo, Egypt, that had captured the world’s imagination that past January and February. Emblazoned on the T-shirt were the logos of popular social media platforms—Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter—and below them, the words “Methods of Freedom.” Tahrir Square became a place of fixation for many across the world as it marked the birth of Egypt’s Arab Spring uprising on January 25, 2011, which eventually forced the resignation eighteen days later of dictator Hosni Mubarak. This attention was both troubling and inspiring. The fascination I had observed with Egypt was not necessarily due to the fact that such a massive mobilization actually occurred, but it was related to the myth that such an act of democracy was primarily made possible thanks to protesters’ use of Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and other social media platforms.1

Purchasing the T-shirt, I walked around central Cairo for the next several hours asking people about the story that it told. “We thank Facebook for our revolution,” a subsistence laborer from the nearby neighborhood of Giza commented while asking me to let Facebook know that “we need their help to organize our next government.” In response to the question whether he or any in his family or neighborhood had Internet access at the time of the initial revolutionary period or even today, he simply answered “no.”

Having collaboratively designed and developed digital technology with diverse populations across the world for more than a dozen years, I was alarmed by the “Facebook revolution” moniker making the rounds, recognizing that this discourse would ignore the inspirational and brave actions taken by protesters. It would simplify their creativity and agency into a story of “technology magic.” This drove me to visit friends in Cairo, determined to unpack a deeper understanding of new media’s role in the ongoing uprising. From 2011 to 2013, I worked actively within Egypt to explore the factors shaping the unfolding political environment.

Facebook and Twitter were accessed in fewer than 10 percent of Egyptian homes in early 2011.2 Yet they are seen as tools that caused a revolution in a country of 85 million. Without an approach that views technology use relative to the contexts of culture and place, we continue to buy into a myth whereby Silicon Valley supplants Cairo in our understanding of political events in Egypt. We see activists and protesters outside the West as incapable of enacting change without the use of “our” transformative tools. Indeed, such a myth is so pernicious that it had even reimplanted itself on the streets of Cairo.

My fieldwork reveals that there is a story to be told that includes technology without putting it at the center. I learned that far more interesting than the fact that the Internet was used by a small fraction of activists, were the creative ways in which its use could coordinate with a range of other mechanisms of mobilizing protest and shaping activism. Many whom I met were well aware of the shortcomings of different technology platforms, yet utilized these strategically to shape international audiences and journalists while focusing on offline strategies within their nation.

The lessons I have learned from this fieldwork bring home the argument of this book, of debunking global, universal, and natural myths associated with new technology to instead pay attention to the agency of communities across the world. In so doing, we can recognize the potential of grassroots users to strategically employ technologies to support their voices and agendas. We can build upon this to consider how technologies can be designed and deployed through collaborations. While chapter 2 illustrates this around the theme of digital storytelling and economic development in South India, the chapters that follow consider how these insights can allow us to revisit the design of technology, to support network building amongst and within marginalized communities (chapter 3), and respect indigenous ways of describing and communicating cultural knowledge (chapter 4).

Paths and Possibilities

To consider the collaborations I describe in the upcoming chapters, it is important to recognize the paths from which the technologies we engage with today have arisen. This chapter brings to light some of the different actors, philosophies, and cultures throughout history that have shaped the digital world. In so doing, we can consider how people across the world can become creators, designers, and activators of technology rather than silent users.

As new media technologies incorporate many of the affordances and functions of “older media,” at times resembling everything from the television to the telephone, it is far too easy to presume that their mere existence or use will empower democracy. Others rebut these claims by pointing to examples of technological surveillance,3 invisible labor,4 and the disproportional ability of the limited few to monetize data.5 Relative to the worlds of capital-intensive older media, the decentralized use of new technology would seem to empower the voices of many, seemingly making possible what media scholar Henry Jenkins has described as a “participatory culture.”6

It cannot be denied that digital platforms of media production, such as YouTube and Facebook, also build profit and financial value for those who control the data and monetize it through targeted advertising. Scholars of political economy, such as Robert McChesney,7 have pointed out how media industries such as Viacom or Disney have increasingly coalesced into massive conglomerates that manage multiple content streams, thereby manipulating their audiences. It raises a similar question in terms of how we may think of social media technologies, including those who are seen as central to the “sharing economy.” Are the Googles, Facebooks, or Baidus of the world monopolies in the making due to their control of how information is classified and retrieved?

One mechanism by which the protocols underlying Internet and social media technologies shape our world relates to the ubiquity and power of invisible algorithms. Media theorist Alex Galloway has argued that the very architecture of the Internet, packet-switching TCP/IP technology, is an example of how protocol limits the nature of participation. Protocol may be faceless, but by critically interrogating historical and contemporary examples, one can recognize how power is not just constituted through formal classifications but also through “open networks.”8 Galloway locates these design protocols within particular histories, for example, the U.S. military’s Advanced Research Projects Agency’s (ARPA) relationship to surveillance systems used during the Cold War. He asks us to question the assumptions built into social media platforms, considering who benefits from their design. He asks us to consider what is seemingly invisible, for example, the flow of data between environments like Facebook and the other websites, mobile phone providers, and corporations whom these technologies serve. With these systems, the protocols, algorithms, and “codes” of the technology usually remain locked, limiting the type of participation they make possible. Adding to this problem is the great trust with which algorithms are accorded, treated as supposedly neutral, truthful, and advanced instruments of knowing and ordering.9

Invisible, and often algorithmic, forms of ordering thus fuel the engines of labor, allowing corporations and states to develop “new” techniques for valorizing human activity. We can recognize such invisibility in action relative to many examples within today’s digital “sharing” economy. Call center workers disguise their accents, names, and locations. Uber drivers are denied benefits and instead hired as contractors. Customer service has been delegated to automated bots and knowledge bases.

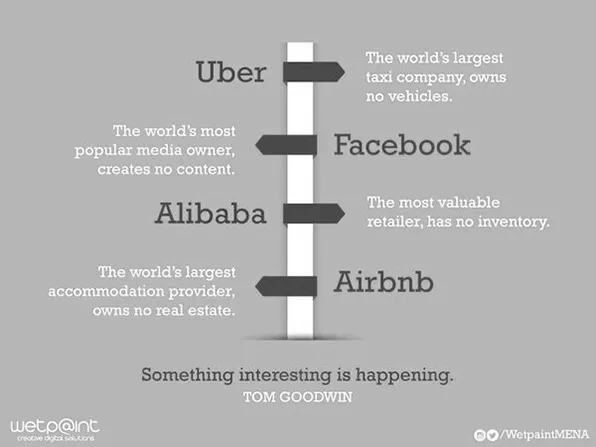

Tom Goodwin, senior vice president of strategy for Havas Media, recently released a compelling graphic that reveals how inventory is no longer owned but managed by lucrative digital middlemen corporations (Figure 1.2). Having power over the infrastructures of sharing presents incredibly lucrative opportunities for sharing economy corporations.

Powering new digital economies are the contributions of content producers, posting content for others to see (e.g., Facebook or Twitter), sharing photographs (e.g., Instagram), and opening up a home (AirBnB). All these forms of personal data are now available for algorithmic ordering and filtering, and in turn for targeted advertising.

Controlling information can thus be seen as the “oil” of the new digital economy. Yet instead of democratizing our world, critics argue that it has helped shape new oligopolies.10 We may best understand new globalized technologies by looking “behind the curtain”—scrutinizing the political economies associated with a technology’s design and use. We can think of alternatives whereby apps could work with labor unions, for example, rather than relying on flexible contract labor without benefits or insurance.

Search engines are an important area where such critique is needed because of the social and political choices encoded into their underlying algorithms. These determine what information is made available (versus left untouched and invisible), how web pages are indexed, and how social concepts like relevance are technically instantiated. It is important to examine who profits and benefits by the ways in which an algorithm, or any technology for that matter, is constructed, deployed, and embedded. Users may be unaware of the values coded into technologies and of the alternatives that exist. Marketing dollars, public cache, governmental buy-in, and popular culture may lead users away from noncommercial technologies created by those without the resources or capital to exploit markets using search-engine optimization.

If we simply take the invisible, ubiquitous, and opaque algorithms that shape our digital experience for granted, even if they are designed for the “public,” we may continue to objectify and subordinate those already residing in positions of disadvantage. Scholar of race and technology Safiya Noble11 has researched the representation of black women via Google search results, revealing how the system reifies sexualized and objectified stereotypes. Simply sharing the logic behind the search results, though an important first step, is far from sufficient. The ability of the falsely represented to control and correct such search results would advance a sense of justice otherwise missing in the online experience.

It is far too easy to presume that a proprietary algorithm serves the public interest. Yet corporate slogans, rhetoric, and discourse push this myth. We are all familiar with Silicon Valley-produced phrases such as “Don’t be evil” (Google) or “Think different” (Apple). We see the deification of the late Apple cofounder Steve Jobs. And we increasingly see public language being appropriated to support basic capitalist activities such as buying and selling a greater range of products. A notable example of this is introduced in Chris Anderson’s “Long Tail,”12 which argues that making more services and products available for purchase is an example of “democratization.” Anderson argues that Amazon, Netflix, and other corporations support “open democracy” by allowing their users to access a greater range of information than ever before and allowing the “misses” to be sold as well as the “hits.”

The dynamics I have described speak to the ambivalent and complex set of questions associated with new technology. While Facebook-provided content may provide a user with a valuable service, it can also be seen as providing free labor that provides resources to a limited number of employees (and corporate shareholders) who have created a software platform that relies on the unpaid contributions of its users. What is celebrated as a “cognitive surplus”13 can be seen as exploitative from the perspective of labor theorists.14 Corporate technologies can easily masquerade as public spaces without being publicly accountable.

An example of this relates to the term “Internet freedom,” which is bandied about today and uncritically celebrated. We fail to consider the political agendas or philosophical underpinnings of these concepts. In his astute 2007 film, Trap: What Happened to Our Dream of Freedom, BBC filmmaker Adam Curtis explains how political philosophies of the early 1980s (in the United Kingdom and United States) shaped a world where politicians surrendered to the free market under the ruse of supporting individual freedom. Transcendental Western concepts such as liberty and freedom were subverted by a system that supported the protocols of elite scientists and technocrats. By blindly trusting numbers, surveys, and black-box technologies, Curtis explains how the public lost an alternative notion of freedom that trusted in the voices and perspectives of its diverse cultural constituencies. From Curtis’s perspective, individualistic freedom may atomize society and in its worst cases give rise to the oligopolies recounted by psychoanalyst Eric Fromm15 in his discussion of Weimar Germany’s transformation into Nazism.

The economic, political, and social influences that shape the design of technology refer to what philosopher Andrew Feenberg calls “technical code,” or “a background of cultural assumptions literally designed into the technology itself.”16 Technical codes represent invisible discourses and values that shape the design and deployment of the technological artifact and if analyzed, may reveal the ways in which tools and systems are socially, culturally, economically, and politically constructed.

A sociotechnical perspective sees technologies not simply as tools that neutrally work to accomplish particular tasks, but rather as intertwined with social processes. Societies and technologies mutually construct and shape one another from this understanding. Yet such a perspective remains uncommon in the mainstream contemporary experience of technologies. We assume the neutrality and functionality of such tools and only recognize their underlying infrastructures when they fail.17

Feenberg points out that technical codes are only visible when they are in flux. While these points of visibility may be easily assumed to be examples of “failure,” they actually represent great moments for productive reflection where users, designers, citizens, and ...