![]()

APPENDIX 1

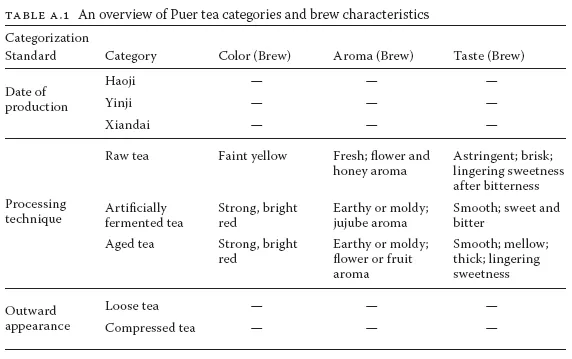

Puer Tea Categories and Production Process

PUER TEA CATEGORIES

Date of Production

Old family commercial brands (Haoji). These are the earliest Puer tea products, produced during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by private family tea companies in what is now Xishuangbanna (including the Six Great Tea Mountains and Menghai) and Simao. Those originating in the Six Great Tea Mountains are regarded as the earliest. Most of this tea is now kept in museums or held by connoisseurs, mostly in rounded cake form. Famous brands include Tongqing Hao, Songpin Hao, Tongxing Hao, and Tongchang Hao, all of which were old family commercial brands in the Six Great Tea Mountains (figs. 1.1 and 1.2).

Puer tea imprinted with the Zhongcha brand (Yinji). Zhongcha is the brand name of the Chinese Tea Company, and for Puer tea it refers specifically to the Yunnan Provincial Branch. The Zhongcha brand mark is composed of the Chinese character

cha (

) in the center, encircled by eight

zhong (

) characters (figs.

1.3 and

4.2). The tea was produced from the late 1930s to the 1980s by the national tea factories of Menghai, Kunming, and Xiaguan.

Modern (Xiandai) tea produced since the 1990s, when private tea companies reemerged and the Puer tea industry boomed in Yunnan.

Processing Techniques (Especially Fermentation)

Raw Tea (sheng cha or sheng pu)

Raw Puer tea hasn't been fermented and is closer to green tea. It can be very astringent when young. Raw Puer tea is available in loose form or made into various compressed shapes.

Artificially Fermented Tea (shu cha or shu pu)

The technique of artificial fermentation was formally invented in Kunming in 1973. By subjecting raw tea leaves to a specific temperature and humidity, the fermentation of Puer tea (mainly microbial enzymatic reaction) is completed within two or three months. Artificially fermented Puer tea is also available either compressed or in loose form.

Aged Tea (lao cha)

This is raw Puer tea that has been “naturally” stored for at least five years, though clear agreement hasn't yet been reached on how many years’ storage is required. It is believed that “natural” fermentation (mostly oxidation, possibly also with some microbial enzymatic reaction) occurs during long-term storage. The older the tea, the higher its price. But “natural” is a relative concept, because some people also create a humid storage environment to accelerate fermentation, which resembles the technique used to produce artificially fermented Puer tea. Some artificially fermented Puer tea that has been stored for several years is also considered aged tea.

Outward Appearance

Loose Tea (sancha)

Puer tea in loose form (see fig. I.3).

Compressed Tea (jin cha)

Puer tea in various compressed shapes, including round, brick, mushroom, and bowl-shaped (see fig. I.4).

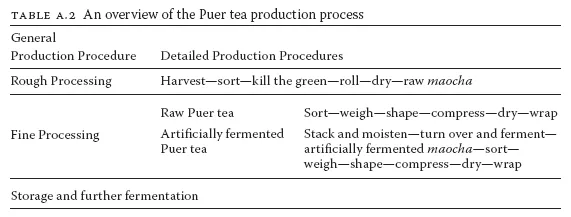

PRODUCTION PROCESS

Rough Processing and Maocha

The process of harvesting, sorting, “killing the green” (see below), rolling, and drying. The final product of rough processing is maocha, the dried basic tea leaves in loose form.

Harvesting/Picking

Harvesting starts in February or March. Tea leaves sprout continuously throughout the spring, summer, and autumn (usually until November), but spring tea is the best. Summer tea is regarded as inferior because the abundance of rainy days could result in a lack of aroma and increased astringency in the flavor of the tea. In China, people usually pick one bud

plus two leaves from each sprout, but for Puer tea they often pick two or three extra leaves.

Sorting

Sorting involves removing rotten or fragmented tea leaves and separating the leaves into different grades. Fresh tea leaves are sorted soon after picking, and maocha is also sorted for further fine processing.

“Killing the Green” (sha qing) / Stir-Roasting (chao cha)

“Killing the green” is one way to deactivate oxidation and the action of enzymes and to suppress fermentation in tea leaves. Different methods of killing the green result in different flavors of tea. For example, steaming is popularly used on Japanese green tea, and sun-drying was used before other methods were invented. Puer tea leaves are stir-roasted without oil. Traditionally, fresh tea leaves were placed in a large, dry wok heated by charcoal or wood, and workers used gloved hands or bamboo sticks to turn the tea

leaves until their color and quality changed, but in modern processing, stir-roasting is done by a machine.

Rolling

The purposes of rolling are to (1) achieve different tea leaf shapes; (2) facilitate storage, maintaining crispness and avoiding breakage; (3) allow the tea brew to be easily released in later infusing, and, with different degrees of rolling, to result in different flavors. Again, rolling was traditionally done by hand but is now done by a machine.

Drying

Drying occurs at various stages of processing. Loose tea leaves are dried after rolling, and compressed tea is dried before wrapping (and sometimes also after wrapping). In fine weather, tea is dried in the sun; in inclement weather, it is baked (by fire or in a large oven).

Fine Processing

Fine processing turns loose maocha into compressed and wrapped tea. In fine processing for raw tea, maocha is steamed, shaped by machine or by hand, pressed, dried, and wrapped. In fine processing for artificially fermented Puer tea, maocha is piled indoors under a specific temperature and humidity. A microbial enzymatic reaction, one kind of fermentation, takes place to mature the tea. This usually takes two or three months, during which the piled tea material needs to be turned over several times to ensure that it is completely fermented. Then, after drying, the same fine processing procedures used on raw Puer tea are applied: steaming, shaping, compressing, drying again, and wrapping.

Storage

All Puer tea—whether compressed and wrapped or loose maocha, raw or artificially fermented—can be put into storage. This is increasingly regarded as an extended and essential part of Puer tea's production, and it is said that the taste of Puer tea is improved by long-term storage.

Fermentation

Puer tea is fermented by two methods. The first is oxidation. When tea comes into contact with air, oxidation happens. As stated above, killing the green suppresses the oxidation to a certain degree. The second method of fermentation is the result of a microbial enzymatic reaction, which is used for artificially fermented Puer tea. Natural fermentation occurs during long-term storage of either raw or artificially fermented Puer tea. “Natural” is a relative concept, as some artificial methods—such as creating a humid storage environment—may be further applied. In this “natural” postfermentation, both oxidation and microbial enzymatic reaction may occur, depending upon the temperature and humidity of the storage.

![]()

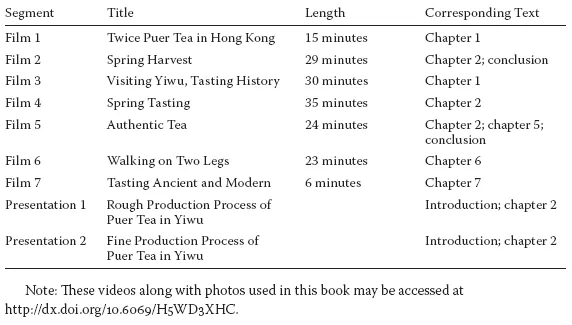

APPENDIX 2

Supplementary Videos

![]()

NOTES

INTRODUCTION

1 I borrow the terms terrace tea and forest tea from Nick Menzies (2008).

2 According to the Mengla County Annals (EBMCA 1994: 226), terrace tea planting started in the 1960s. But in Yiwu, many tea farmers told me that larger-scale terrace tea planting commenced in the 1970s and 1980s.

3 Zhu Zizhen (1996), a scholar of tea history, argues that the transition from compressed tea to loose tea had occurred before this period. But it is likely that the emperor's command encouraged the production of loose tea. Strictly speaking, compressed tea—pressed with loose leaves—is different from molded tea made from well-pounded tea paste and popularly given as a tribute to the emperor during Northern Song (960–1127).

4 The botanical origin of tea is under debate. Some argue that tea originated in India (see Baildon 1877) while others say that China—and specifically Yunnan, with its rich wild tea tree resources—is its birthplace (see Chen Chuan 1984; Chen Xingtan 1994; Evans 1992). Still others integrate various statements, placing its origin in the foothills of the Himalayas or in Southeast Asia, including Yunnan, Burma, Laos, Thailand, and India (see Ukers 1935; Macfarlane and Macfarlane 2003; Mair and Hoh 2009).

5 These areas are famous for producing Puer tea, but the northern, central, and southern areas of Yunnan also have tea resources. In addition to Puer tea, Yunnan also produces green tea and red tea (usually referred to as black tea in English) (Chen Xingtan 1994).

6 Some regard the Hani and Jinuo as the earliest tea harvesters in Yunnan (see Gao Fachang 2009: 25–29).

7 In China, large-leaf tea occurs mainly in Yunnan. Other tea areas, such as Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Fujian, and Sichuan, mainly produce small-leaf tea. Yunnan also has its own small-leaf tea, which was transplanted from Sichuan, to the north of Yunnan.

8 Debates still exist in the tea science about the difference between oxidation and fermentation. In reality, it is often hard to judge when oxidation ends and ferme...