![]()

CHAPTER 1

A PROGRESSIVE FOOTPATH

WHEN BENTON MACKAYE CLIMBED STRATTON MOUNTAIN IN SOUTHERN Vermont in 1900 on the trip that would inspire him to propose an Appalachian Trail, the landscape that surrounded him looked much different from the one hikers encounter today. Where we see a thriving ski resort and a lavish condominium development on the north side of the mountain, MacKaye saw a devastated rural community attempting to eke out an existence from subsistence agriculture and logging. Since the 1780s, European settlers had transformed old-growth forests into a scarred and eroded landscape as they struggled to turn the hills of central Vermont into an agricultural Eden. In the 1880s, new pressures were placed on the region's forests when several small lumber mills opened to provide jobs to a struggling population of farmers in the Stratton area. The success of these local mills was shortlived, however, as wealthy out-of-state lumbermen bought up land and put the smaller operations out of business. The new lumber barons ramped up production and set up camps for migratory workers. By 1920, a year before MacKaye proposed his plan for an Appalachian Trail, over a third of the people living in Stratton were migrant lumbermen, and the area's economic future looked uncertain.1

The story of Stratton was not unlike that of many other communities throughout the Appalachian Mountains. In both northern and southern ranges, thin soil, relatively steep slopes, and inaccessible markets limited European settlers' attempts at farming and ranching. Furthermore, the “cut-and-get-out” forest practices of large timber barons left both land and rural populations literally uprooted. By the turn of the nineteenth century, many rural people left for greener pastures out West or for industrialized urban areas, where they faced new problems associated with public health, unemployment, and worker safety. For MacKaye, the problems of the city and of the countryside were inseparable. When he came to Stratton for adventure and recreation in 1900, climbing a tree on the top of the mountain for a better perspective on the landscapes below, he began to envision a project to not only preserve scenic vistas and natural resources along the spine of the Appalachian Mountains but also to protect the people who lived and worked in the surrounding areas and in distant cities.

At the heart of MacKaye's proposal for an Appalachian Trail was the desire to solve “the problem of living,” which, in his view, was an economic one. He wrote, “Living has been considerably complicated of late in various ways—by war, by questions of personal liberty, and by ‘menaces’ of one kind or another.”2 These menaces included unemployment, class antagonisms, the degradation of natural resources, and a kind of spiritual malaise that came from being disconnected from nature. MacKaye had begun to witness mental health problems spreading among his urban friends and family—most devastatingly exemplified by his wife's suicide in 1921. By putting people's spare time to productive use through voluntary service in the out-of-doors, MacKaye believed that the Appalachian Trail project would help ameliorate the angst of modern life.

According to MacKaye's plan, the Appalachian Trail would provide common ground for different parts of American society to come together to create opportunities for recreation, health and recuperation, and employment. When volunteers came together to build this skyline path and surrounding camps, MacKaye claimed, “Industry would come to be seen in its true perspective—as a means in life and not as an end in itself. The actual partaking of the recreative and nonindustrial life—systematically by the people and not spasmodically by a few—should emphasize the distinction between it and the industrial life.”3 As an alternative to the path of industrialization, MacKaye believed that the project would “put new zest in the labor movement…. The problems of the farmer, the coal miner, and the lumberjack could be studied intimately and with minimum partiality.”4

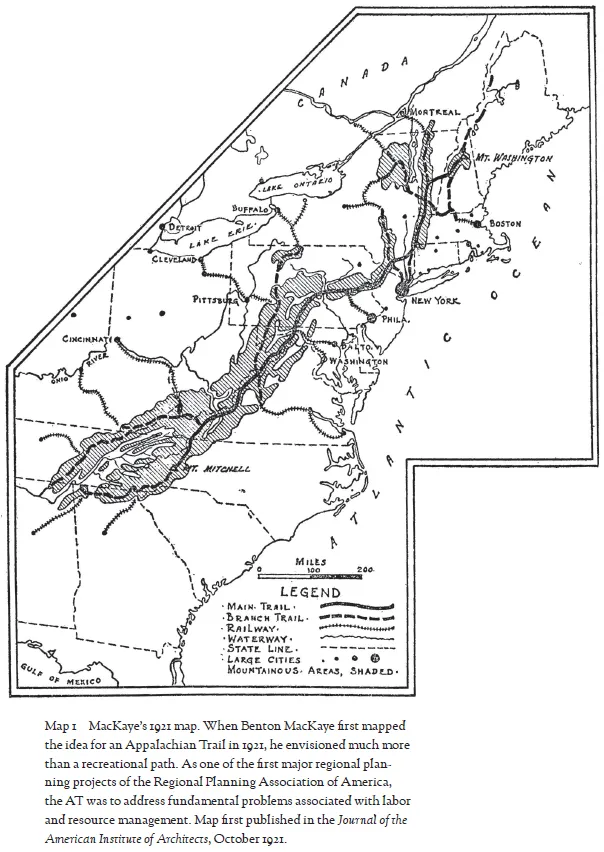

MacKaye's 1921 proposal for an Appalachian Trail included a multitiered plan for developing “outdoors community life” that essentially amounted to the construction of a social utopia in the eastern wilderness, where “cooperation replaces antagonism, trust replaces suspicion, emulation replaces competition.”5 The trail itself would lead adventurers along the ridgeline of the Appalachian Mountains from Maine to Georgia, and provide a “strategic camping base” for the country's work and play.6 Next would come shelters and huts modeled after those built in the White Mountains of New Hampshire and the Green Mountains of Vermont. The following phase—part of MacKaye's proposal that never reached fruition—was the creation of community encampments where people would collectively own acreage along the trail and live in private homes located in small, clustered settlements. Like all phases of the project, MacKaye insisted that these collectives would be established on a not-for-profit basis. He argued that the community camps “should become something more than a mere ‘playground’: it should stimulate every line of outdoor non-industrial endeavor.”7 Camps along the trail would be used for education, recreation, and spiritual and mental healing.

The final component of MacKaye's plan involved camps for food production. Like other aspects of the trail, the government would lead efforts to plan these agricultural centers, but private citizens would be instrumental in their development and maintenance. Although the trail became a conduit for the protection of agricultural lands in and around the Appalachian Trail corridor in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, the kinds of federally planned farm and food camps that MacKaye had in mind did not materialize as he envisioned.

In the 1921 proposal, MacKaye acknowledged that all of these extra economic developments would come after the trail was established. The idea was that the same cooperative spirit and coordinated actions used to blaze the trail, build the shelters, and organize the camps could be channeled to create small agricultural-based communities that would produce food for hikers and rural families. In the valleys below the ridgeline, MacKaye envisioned an “experiment in ‘getting back to the land.’” These centers of production would provide employment and “opportunities for those anxious to settle down in the country.”8 People might come to the trail and, upon finding spiritual fulfillment, would never want to leave the hinterlands. Thus, MacKaye believed that the AT could help reverse the trend of rapid urbanization and the problems of modern American life.

MacKaye's 1921 article was a bit vague about how to achieve the ambitious goals he proposed; he wrote, “Organizing is a matter of detail to be carefully worked out.”9 Not long after the proposal was published, however, MacKaye suggested that the AT project would require new forms of political engagement—a combination of decentralized and centralized power.10 Like many of his Progressive counterparts, MacKaye believed in state-supported, technocratic solutions to natural resource problems. He felt that federal foresters, engineers, architects, and planners should all be involved in developing the AT. Yet he maintained that the Appalachian Trail project would be successful only if private citizens played an active role. He emphasized that the AT would ultimately rely on citizen volunteers and amateur “out-of-doors people”:

For without the will-to-do that comes from the people at large the technician's hands are tied. The amateur, as a representative of the people, is needed quite as much as the technician. He is needed not to look on, but to take part, to take his hand in planning and surveying. And if he goes astray the expert can correct. The professional should guide, but the amateur should do.11

Although MacKaye suggested that “some sort of general federated control” of local volunteers could be established to build the trail, he did not outline explicit plans as to how development should proceed. MacKaye's lack of detail was intentional; he wanted to first stir people's imaginations, not bore or alienate them with logistics. He believed that “people seem to be more interested in something which they do themselves than in what someone else does for them.”12 In light of this realization, MacKaye thought that the project “should grow and ripen rather than be suddenly created” by outside forces.13 The notion that ordinary outdoors people should lead trail development efforts reflected MacKaye's desire to balance the trained professionalism of government experts with the everyday knowledge of local people. This balance and exchange of knowledge and authority lay at the heart of trail-building efforts not only during its early days in the 1920s and 1930s but throughout the course of the trail's history.

This system of entwined decentralized and centralized authority was part of MacKaye's broader political objective for the AT. For MacKaye, the project would not only promote the environmental and economic health of the country, but by promoting citizen involvement in natural resource management, it would also contribute to the political health of the nation. For MacKaye, the AT provided a place to empower American citizens and workers while at the same time exploring the possibilities of federal planning. Although MacKaye became less involved with the day-to-day development of the trail in the late 1920s and 1930s, his vision for an Appalachian Trail inspired a small group of committed citizens to complete an initial route by 1937.

Historians such as Larry Anderson, Robert Gottlieb, and Paul Sutter have begun to peel apart the many layers of MacKaye's eclectic mind and illustrious career. They have pointed out MacKaye's important—and often overlooked—ideological contribution to American environmental history, and have used his ideas to challenge conventional interpretations of the conservation movement during the Progressive Era.14 While many historians have portrayed Progressive conservationists as being primarily interested in economic efficiency, watershed protection, wilderness, and wildlife, recent scholars have demonstrated that MacKaye and a handful of his colleagues, such as Raphael Zon and Bob Marshall, were also concerned about social justice and labor issues. Embedded in MacKaye's regional plan for an Appalachian Trail was a radical call for a reawakening of civic America; he believed that through collective engagement in nature and cooperative trail building, citizens of all sorts could work together with the state to build this important national resource. In addition to protecting the nation's natural heritage, the Appalachian Trail would be a symbol of the country's rich political capital. To understand how the Appalachian Trail unfolded in the twentieth century, we must first dive deeply into MacKaye's ideas about the political mechanisms for building the Appalachian Trail and the broader social objectives that he hoped the project would help achieve.

PRELUDE TO THE FOOTPATH

Understanding the origins of the Appalachian Trail proposal requires an examination of the political and cultural influences that shaped Benton MacKaye's thinking during the Progressive Era. As the environmental and human effects of industrial progress became evident at the turn of the twentieth century, critics of industrialization became more vocal. Preservationists and conservationists sought to protect America's forests from the plunder of large timber companies. Labor advocates campaigned to promote the health and financial security of workers. Urban reformers struggled to cope with the slumlike conditions associated with expanding urban populations. By the early 1920s, regional planners were working to mitigate the effects of agricultural depression in rural areas while urban workers began seeking places to get away from it all and reconnect with nature. Each of these movements—wilderness preservation, outdoor recreation, forest conservation, labor activism, urban reform, and regional planning—have distinct histories. Yet they were also linked in complex and unusual ways.

Underlying each of these movements was an emerging idea that the centralized government should take a stronger lead in efforts to protect the nation's resources. At the same time, this era also saw the growth of private organizations devoted to recreation and land preservation, such as the Appalachian Mountain Club in the Northeast and the Appalachian National Park Association in the South, and these organizations began to work closely with federal partners to achieve broad goals. The AT project was similar to other conservation projects undertaken during the Progressive Era in that it involved the technical expertise of federal bureaucrats, while at the same time engaging a growing number of private citizens interested in experiencing and protecting America's hinterlands. Unlike related projects, however, the AT differed in the form and degree of partnership between public and private players. From its origins, the AT project involved a range of different private groups and a variety of governmental agencies.

Perhaps the most obvious audience for MacKaye's Appalachian Trail proposal was a growing number of advocates for outdoor recreation and wilderness preservation. By the mid-nineteenth century, Americans began to view wilderness less as a frightening place that needed to be subdued and more as a place to explore nature's beauty.15 Poets, artists, and philosophers began to seek inspiration from America's scenic landscapes, and by the 1870s, well-to-do easterners became interested in active forms of recreation—hiking and climbing mountains—instead of passively soaking in sublime scenery.16

Many of these early American outdoor enthusiasts were inspired, in part, by European examples. By the early nineteenth century, walking had become a pleasurable ritual for working people in England and in other European countries. The York Footpath Society was established in 1824, and in the 1930s its members had worked with the Manchester Society for the Preservation of Ancient Footpaths (established in 1826) to develop and maintain local trails in the British countryside. These early footpath preservation movements were made possible by changing economic conditions and the emergence of a working class.17

MacKaye and his colleagues believed that a similar movement could take place on American soil. Just as American planners had been influenced by European counterparts such as Ebenezer Howard and Patrick Geddes, MacKaye and other trail enthusiasts were inspired by English ideas about developing trail systems. In the 1860s, professor Albert Hopkins of Williams College was the first American to organize a hiking club—the Alpine Club of Williamstown, Massachusetts—primarily for the extracurricular education of his students. In New York, botany professor John Torrey soon followed by forming the Torrey Botanical Club at Columbia University. In 1876, professor Edward C. Pickering organized a group of MIT and Harvard affiliates and established the Appalachian Mountain Club (AMC). The AMC is still active today and is the nation's oldest continuously operating mountain club. Before the twentieth century, the early mountain clubs primarily served social functions. The clubs were generally exclusive—professors of elite institutions and other powerful figures with long summer vacations were common among their ranks. Early club members tended to be more interested in socializing and walking on trails than in building them and, for the most part, paid laborers built the first recreational trails in remote areas like the Presidential Range in New Hampshire.18

As the demand for recreational trails increased, leaders of hiking clubs throughout New England realized that they needed to develop more extensive routes and new organizational models that would involve more people in the trail-building process. In 1910, James P. Taylor, headmaster of the Vermont Academy for Boys, suggested a new approach for building footpaths. Instead of the circuit routes developed by hired hands or the trails built on public lands by public officials, he proposed organizing a group of volunteers—the Green Mountain Club—to build a “through trail” across Vermont from the southern Massachusetts border to Canada. Known as the Long Trail, Taylor explained that the footpath would expose hikers to different kinds of local places with unique combinations of topography, vegetation, and cultural elements within the state. He played on Vermonters' sense of independence and autonomy by emphasizing that the state's citizens would control the project's destiny; the Long Trail would be something unique to Vermont—a symbol of Vermonters' self-reliance and an expression of regional identity. T...